As I mentioned a few days ago, two articles were recently brought to my attention (one from 1901, and the other from 1914) about the discovery of what appeared to be Native American remains on the property in downtown Ypsilanti we today call Water Street. Well, I followed up with the fellow who sent these articles to me, a local historian by the name of Matthew Siegfried, in hopes of learning more about Ypsilanti’s Native American past, and what was found on the Water Street site 100 years ago. What follows is our admittedly lengthy, but thoroughly fascinating discussion.

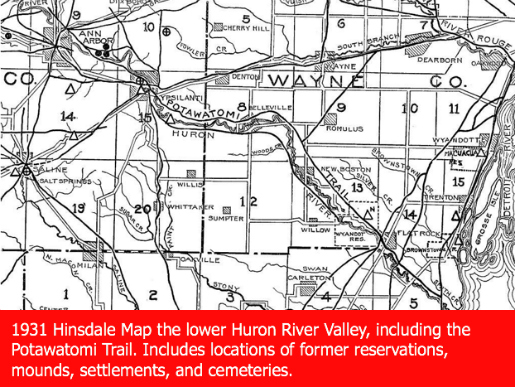

MARK: Over the years, I’ve heard a few different people suggest that, while a number of tribes passed through Ypsilanti, either by way of the Huron River, or one of the numerous Indian trails, like the Pottawatomi Trail (see map below), none really called this area home. “Sure,” I’ve been told, “they may have hunted here and buried their dead along the banks of the river, but they didn’t actually live here.” Would you consider that an accurate assessment?

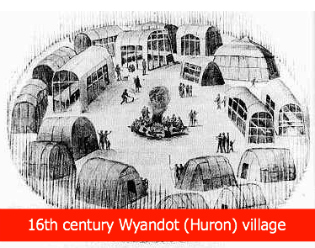

MATT: No. On the contrary, there’s overwhelming evidence for Indian habitation of this area over the past several centuries. The mounds and burial tumuli that were located on the banks of the Huron River, between Catherine and Pearl streets, as well as other area mounds, like those on the campus of Concordia College, which were determined, during early 20th century investigations, to be of the Late Woodland period, would indicate that Indian peoples have had long-term occupations in this area. The existance of local burial grounds, the springs in the area, the large number of converging trails, the cultivated land along the Huron River, and the placement of a French trading post here, all point to significant Native presence in what is now Ypsilanti. The Hinsdale Atlas of Michigan Archaeology also places a Native Amerian village site directly in the area of downtown Ypsilanti, stating bluntly that, “the Wyandot had a village in Ypsilanti.” I believe that there were multiple habitation sites, including villages, from a number of different cultures, stretching back thousands of years. There could also have been long periods where the immediate area was unoccupied. It’s also worth noting that the habitation areas indicated on the Hinsdale maps are just an just an approximation.

MARK: You reference the work of Wilbert B. Hinsdale, who, among other things, authored The Indians of Washtenaw County in 1927. What can you tell us about his research?

MATT: Hinsdale was, like a lot of pioneering archaeologists, not trained in the field, but a well-to-do professional (a medical doctor in this case) with a passion for archaeology. He began collecting artifacts and visiting sites with the aim of consolidating information and systematizing it. Much of his information came from amateur collectors and local informants. After he retired as a doctor, he worked for the University of Michigan as custodian of their collection. He published the atlas in 1931, and is considered a founder of modern archaeological practices in Michigan. His atlas has long been referenced and contains much valuable material. (Much of his work has been superseded as more as more has been learned and understood, but it’s still a valuable resource.) The atlas gives a good, if limited, view of the Native landscape of Michigan. While a good tool, it is not an exact atlas, and certainly shows only a small fraction of Michigan’s Native sites.

MARK: What does the Hinsdale atlas tell us about Ypsilanti?

MATT: The atlas places a village and a cemetery close to downtown Ypsilanti, where multiple native trails converge. It also shows another village just to the south of Ypsilanti, another cemetery off a trail that is now Prospect Road, and the mounds off Geddes Road, on the present-day campus of Concordia College.

MARK: You mention that Hinsdale’s placement of the Native American village on his map was just an approximation. What, to your knowledge, did he base that approximation on? I suspect, for instance, that he collected oral histories from people who grew up in the area, having heard stories from their grandparents, and I’m curious to know if any record of those interviews still exists.

MATT: Yes, much of his information came from those kind of sources. He also did exhaustive traveling and surveying. The map symbols themselves would cover many acres with the scale he uses, so we take it for granted that he means the general area marked. Whether or not his interviews and notes still exist is a good question. Given his stature and the nature of the institution he worked for, though, I would imagine so.

MARK: I’m just curious if, based upon those interviews, we might be better able to pinpoint the exact position of the village he shows as being in what we now consider to be the downtown area.

MATT: Perhaps. It would be good to find out. This quote, which would have been available to him, from the History of Washtenaw County (1881), makes clear that the current downtown area was the site of what the author calls an “ancient burial ground”:

“This ancient burial ground is now concealed by the four important blocks forming the center of the city. The ground on which Mr. Joslin’s residence [now the Gilbert Residence on South Huron] is built was the nucleus of this old cemetery.”

There may be a number of sites, from different eras and different cultures, located in central Ypsilanti. The most recent occupations would have been by Potawatomi, and anything we could learn about them would be invaluable to our understanding of the region, given their role in the history of the area, including the War of 1812.

MARK: According to research shared by the Huron River Watershed Council, it sounds as though several tribes crossed paths in Ypsilanti. From what I’ve read, there were three major tribes in the area; the Ottawa (Odawa), the Ojibwe (Chippewa), and the Potowatomi, who together formed a loose alliance known collectively as the Three Fires. In addition, as you mentioned earlier, the Wyandot (Huron) were also known to have been in the area. Are there other tribes that may have had a presence here that I’m not aware of?

MATT: It all depends on what period we’re talking about, but, in the “historic period,” many of the villages along the Huron River, all the way to Lake Erie, would have been multi-tribal to some degree. I should note that the term “tribe” is problematic, as these are village societies. In the Ypsilanti area, for most of this period, it would have been the Potawatomi, who were roughly divided into three areas; northern Indiana, western Michigan, and, the smallest group, in the villages along the Huron. We know, for instance, that this area is included in treaty negotiations between the government and the “Huron Potawatomi.”

By the time whites really came into physical contact with Native Americans in Ypsilanti, traditional societies had already undergone large-scale, post-contact dislocation, and each village was also, in part, a refugee camp. They also went through dramatic political, cultural and social changes as they responded and adapted to these new realities, with an increasing tendency toward confederation in the century before their ultimate removal in the 1830s.

MARK: So, which tribes might we have seen here in the 1700s?

MATT: Along the Huron, the Potawatomi and Wyandot predominated by mid-1700s, but there were also members of the Miami, Delaware, Ojibwe, Shawnee (who had a village near the mouth of the Huron), Sauk, Odawa, and a number of other bands in the Detroit area. Generally speaking, the Wyandot predominated closer to the lakeshore, and the Potawatomi in the interior.

It’s important to emphasize that these groups had, and made, their own history. We know, for instance, that smallpox decimated the local Potawatomie villages 1752. And, in 1787, the disease struck the Wyandot villages. And another epidemic in 1813 further weakened an already hard hit population.

And the groups around Ypsilanti would have been active in the defining events of that era. They debated how to use the rivalries between the French, English, and later Americans, to protect and further their own interests. The Wyandot were particularly divided over these questions.

MARK: Let’s talk about those rivalries and how our local Native American population engaged politically with the French, the British, and then the Americans.

MATT: Well, nearly all the local groups were allied with the French against the British in the French and Indian War (1755–1763). And, after the French were defeated in 1763, the Potawatomi were the leading force locally in Pontiac’s War (1763), again trying to drive British soldiers and settlers from the region. And tribal members from the Ypsilanti area would have undoubtedly participated. I should add, it was the Wyandot decision to make a separate truce with the British that helped lead to the collapse of the siege.

The Potawatomi of Michigan also played a large role during the Northwest Indian War (1785–1795), in which a confederation of tribes led by Little Turtle and Blue Jacket fought American expansion into the Ohio River Valley after the Revolutionary War. Eastern Michigan’s Potawatomi also played a conspicuous role in the defeat of the United States Army at Ohio’s Fort Recovery in 1791. This was the largest defeat ever suffered by the American army at the hands of Indians, and warriors from right here in the Ypsilanti area likely fought there. The Huron Potawatomi refused to leave land ceded in the 1795 Treaty of Greenville that ended the war, and, in the following decades, would become strong supporters of Tecumseh’s confederacy.

During the War of 1812, it was the (somewhat releuctant) decision of local Wyandot villages to ally with Tecumseh’s confederation that allowed for the successful siege and capture of Detroit, this time in alliance with the British against the Americans. Among the most important leaders of the confederacy was the Indiana Potawatomi, Main Poc. His forces were concentrated in this area during the runup to the siege and these wartime villages would have included warriors of a dozen tribes from all over eastern America. Huron Valley Potawatomi were, unlike the their more wavering Wyandot neighbors, considered strong allies of the militant Shawnee position led by Tecumseh and his brother during the war.

MARK: And, by the 1830s, they were forced from the area?

MATT: Yes, most Native Americans were removed from southern Michigan by the 1830s. However, the closing of the last Wyandot reservation on the Huron River was not until in 1842 (near present-day Flat Rock), and there were individual Wyandot living on or near their former reservations for years. Some still live in the area. Most of the Wyandot that lived on the Huron were removed first to Kansas and then to Oklahoma, where their descendants live in a community which bears their name.

Some Potawatomi, true to their long-time refusal to leave, continued to live in Michigan, particularly in the area of the St. Joseph River, after the the 1830s. The Huron Potawatomi were removed first to western Michigan, then, in 1840, to Kansas. In Kansas, a number of Huron Potawatomi escaped and returned to Michigan, where they lived near Athens, in Calhoun County, eventually gaining government recognition. And there they remain as the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi, the descendants of generations who called the Ypsilanti area home.

[1909 photo of a Potawatomi community, “after a dance,” in Athens, Michigan. According to Matt, “These are the direct descendants of the Potawatomi of the Huron River. They escaped forced removal in 1840-41 in Kansas, and returned to Michigan.” The image is from the family of Abram B. Burnett, Chief of the Potawatomis (1812-1870).]

MARK: And, going further back, Native American activity in the area dates back some 11,000 years, when the glaciers began to recede, correct?

MATT: Yes, there is definitely evidence, in the form of highly scattered hunting camps, of Native Americans in Michigan since the end of the last Ice Age. It is assumed they were also in the area of the Huron River at that time, though conclusive evidence of Native Americans on the Huron can be dated to around 5,000 years ago.

MARK: But, in terms of mass migration to the area, I’ve heard mention of Algonquian peoples being forced south from Canada’s Georgian Bay by the Iroquois.

MATT: Yes, that would have been during what is commonly referred to as the Beaver Wars, in the 1600s, and before white settlement of the area.There were undoubtedly other, earlier, periods of big population moves that we know nothing about, though. During the Beaver Wars, growing trade with the French brought native groups into intense competition for beaver (and other items) and the trade routes and posts associated with them. These rivalries were fostered by competition among the French, Dutch and English traders themselves, and involved wide swathes of northeastern North America.

The wars resulted in large scale population movements and realignments as Iroquoian groups expanded west from their heartland in New York and Canada. This affected Michigan, and the whole region, including the abandonment and repopulation of much of the state. Many, like the Ojibwe, Odawa, and what would become the Wyandot, were pushed into lower Michigan, while others were pushed out. The Potawatomi moved east from their base around present-day Chicago into southern and eastern Michigan, arriving in the area of the Huron River valley in the century after the Beaver Wars, probably returning to former homelands.

These were a cataclysmic series of wars and would have had profound effects the societies living along the Huron at the time and for generations after.

MARK: And, just to be clear, when we say “Algonquin” we’re talking about tribes, including the Ottawa, Ojibwe and Potawatomi, that all would have shared a common linguistic ancestry.

MATT: Yes, Algonquin is a linguistic definition. As many cultural differences can exist between Algonquian speakers, though, as between Algonquian speakers and others. The Odawa, Ojibwe and Potawatomi speak different languages, but they’re from the same branch of the Algonquian family. Groups like the Shawnee, Miami and Fox spoke other Algonquian languages. However, the Wyandot, Erie and others who lived in the region spoke languages of the Iroquoian family. There were even some Siouan speakers like the Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) in the area of Detroit.

MARK: So, these early inhabitants of this area were primarily nomadic hunters and gatherers who would pursue large mammals and other game across SE Michigan. And, at some point, groups began cultivating crops and establishing less transient communities. As I understand it, of the Three Fires tribes, the Potawatomi were the most inclined to settle down in such a way, and commit to agriculture. Assuming this is true, would it, in your opinion, be most likely that, if there were an agricultural Native American community in what we now call Ypsilanti, it would have been Potawatomi?

MATT: Cultivation really got going in Michigan during the Late Woodland period, which, in this area, would have been around 600-800 CE. Though I would not assume, given the nomadic nature of this people, that there’s any direct connection between the populations doing the cultivating and those who were here at the end of the ice age. Thousands of years separate the two periods and there were undoubtedly great movements and mixtures of peoples in the interim.

For example, a recent genetic test of 2,000 year old burials in the Hopewell Mound in Ohio found, that along with the main genetic groupings, ”links also are indicated between one or more of the individuals from the Hopewell site and tribes as diverse and widespread as the Apache, Iowa, Micmac, Pawnee, Pima, Seri, Southwest Sioux, and Yakima,” indicating the kind of movement that was undertaken by some Native populations over generations (and even individuals over a lifetime).

While nearly all Michigan Native American groups were practicing some form of agriculture by the time of contact, it would be natural for those like the Potawatomi and Wyandot who inhabited the southern Great Lakes, for agriculture to be a greater part of their lifeways. The Odawa and Ojibwe were generally living in the northern Great Lakes, with a far shorter growing season which meant that they were more reliant on hunting and forage.

Given what we know of the region’s Indian history, it’s possible that earlier Wyandot settlements were later replaced by the Potawatomi (who may have been returning to ancestral homelands). It’s also possible that both groups were living nearby at the same time. By the early 18th century, the immediate Ypsilanti area was probably inhabited by Potawatomis, however it should be noted that there were well established Wyandot villages north of Flat Rock, less than twenty miles down the Huron at the same time.

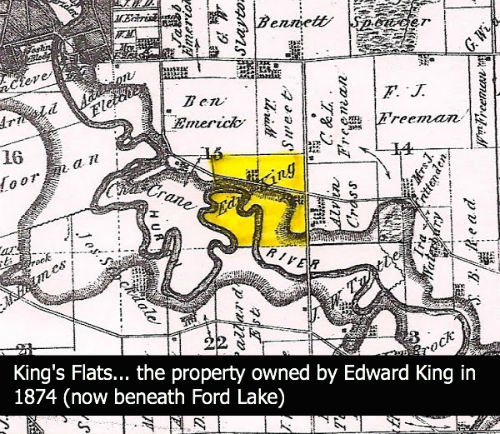

There was evidence of native cultivation in King’s Flats (where Ford Lake is now), which was undoubtedly used by groups living where the city of Ypsilanti now is. Many areas could have been used for garden beds utilizing the rich soil along the bottomlands of the Huron, including in Ypsilanti proper. The Wyandot in this region called the Huron River “Giwitatigweiasibi,” meaning somethng like “burnt-grove region.” Native peoples were managing the forests, especially through fire, all along the Huron. They did this in order to attract game, clear brush and trees so that they could plant crops, and to enrich the soil. The whole of the area would have been part of a landscape that was made use of by groups living in and around what is now Ypsilanti.

Even after agriculture firmly took hold, hunting and foraging continued. Many villages remained seasonal affairs, as Native peoples would often relocate to coastal areas or disperse into interior hunting camps, depending on the season to regather at planting and harvesting times, which were also times of ceremony and celebration.

[Image from Dusty Diary.]

MARK: When is the first documented interaction between Native Americans and Americans of European ancestry in what we know today to be Ypsilanti? Do we, for instance, have entries in journals kept by French fur traders? Do we have letters written by the first settlers of Woodruff’s Grove in 1823, in which they describe their interactions?

MATT: I believe someone in the party of de La Salle documented their trip when they came down the Huron in the 1680. These would have been the first Europeans in this area. There is also quite a bit of documentation of the area surrounding Detroit, which would be pertinent to the study of any groups living on the Huron at the time. Much of the earliest interactions between local Indians and Europeans was through the French, including diaries from the French traders in Fort Detroit during Pontiac’s War in 1763. These offer some of the earliest and most vivid, if flawed, contemporary accounts of Indian actions in the area.

MARK: After that, the first report I’m aware of was penned by a British officer who, in 1772, was traveling on the Sauk Trail, heading toward the Mississippi River from Detroit. In the report, according to information shared by the Ann Arbor District Library, he described an area 40 miles west of Detroit which the the Indians called “Nandewine Sippy.” He also described six large cabins of “Puttawateamees” near the Huron River. And the Huron, he said, was about fifty feet wide and about one and a half to two feet deep. And the road, he added, was “very bad in this place.” [note: According to other sources, Nandewine Sippy was the native name for the Huron, and not the Native community where Ypsilanti now stands. It’s conceivable, however, that it was used to refer to both.]

MATT: There are also accounts from the 1780s and 90s in the Michigan Pioneer Collection… While they weren’t the fist, Frenchmen Gabriel Godfroy and Romaine La Chambre are probably the best known fur traders in what is now Ypsilanti. They opened their post near the Huron River (just north of Michigan Avenue) in 1809, most likely in close proximity to a Potawatomi settlement. It’s also worth noting that evidence exists to suggest that it’s likely a continuation an earlier trading post.

MARK: Back to the British officer in 1772, is it just coincidence, in your opinion, that “Nandewine Sippy” sounds somewhat like “Ypsilanti”?

MATT: Yes, but if it ever came up for a vote I’d enthusiastically pull the lever for Nandewine Sippy.

MARK: You mentioned Blue Jacket earlier. Do I understand correctly that there may be evidence of him having spent time in Ypsilanti?

MARK: You mentioned Blue Jacket earlier. Do I understand correctly that there may be evidence of him having spent time in Ypsilanti?

MATT: There are a number of accounts that Blue Jacket was here, somewhat ironically, as an honored guest in what is supposed to have been the first Fourth of July celebrated in the area, on July 4, 1824. As Blue Jacket died sometime right before the war of 1812, though, it’s likely his son Jim who was here. Jim married a Wyandot woman and moved with the Wyandot to the reservation on the Huron around 1818 (along with Blue Jacket’s widow). Jim, Blue Jacket’s oldest surviving son, became a prominent leader of the reservation and it was probably him who the settlers reference. He was a leading supporter of Tecumseh and was removed with the Wyandot in 1842. His wife died during removal and Jim died in Kansas around 1845.

Blue Jacket himself, though, likely spent time in the area as well. He had a village on the Detroit River in the the late 1700s, and, though a Shawnee, he held great authority over many of the Wyandot and other groups of the area. Though he would come to make his peace with the United States, he was a brilliant political and military leader during the Northwest Indian Wars and helped to organize many of the villages in the vicinity of the Huron River to fight the Americans. He may even have traveled to Nandewine Sippy on just such a mission.

On a related note; my wife’s direct maternal ancestors (a mother and her daughter) first arrived to the Detroit area as captives of Blue Jacket from Kentucky, during the American Revolution. They lived at his village for many years, by all accounts doing the cooking and learning the Shawnee language. They ended up going to Canada after the American victory, along with the British loyalists and defeated Indians.

MARK: You noted earlier that some archaeological work had been done on the Concordia campus in the early 1900s. Are you aware of any significant archeological work ever having been done along the Huron River, though, in hopes of determining how significant the Native American presence may have been in the area?

MATT: Very little archaeological work of any kind has been done, either in the City, or in the immediate vicinity. So much of the Native landscape was destroyed in the first decades of white settlement that many assumed the City to be devoid of surviving archaeology. And, most of what was done, was done in a time when archaeology looked a lot like looting. And then, of course, there was the straight-up looting, which was practiced by many early Ypsilantians. A series of survey pits were dug in Riverside Park in 1980, and the area around the old Worden House on Huron Street was looked at in 2002. Work has been down in the Huron Metroparks, south of Ypsilanti, much of it by EMU’s Archaeology Field School. Most of it has been survey-type work, but they’ve uncovered hundreds of artifacts and documented a number of sites. That said, there is probably not a mile along the Huron River between here and Lake Erie without some evidence of the area’s Native past.

MARK: What’s your background?

MATT: I received a BS in History and an MS in Historic Preservation from Eastern Michigan University. I’ve volunteered at various local archaeological sites, including at Native American sites in the Huron Metro Parks, where I also worked with the Archaeology Field School. As part of a Fellowship in Graduate School, I also worked at the Michigan Historical Center while getting my Masters. There I researched and wrote dozens of Michigan Historical Markers, including for a number of Native American sites. The main focus of research while in college, and the subject of my Masters project, has been Ypsilanti’s historic African American community.

I grew up in Cincinnati, Ohio and spent much time at my Grandfather’s farm just up the road from Serpent Mound. His farm gave up stone axes, grinding stones, and points. He used one big stone axe he found as a door stop. I’m sure that’s where my appreciation and curiosity of the region’s Native American world began. Over the years, I’ve have travelled Ohio extensively visiting dozens of mounds, earthworks and other sites and have written more school papers than I care to mention on the subject.

MARK: Aside from the mounds which were documented along the Huron, and the fact that, over the years, a significant number of artifacts have been discovered by Ypsilanti residents, does any physical evidence exist that a village, or any kind of semi-permanent Native American community, may have existed here?

MARK: Aside from the mounds which were documented along the Huron, and the fact that, over the years, a significant number of artifacts have been discovered by Ypsilanti residents, does any physical evidence exist that a village, or any kind of semi-permanent Native American community, may have existed here?

MATT: The kind of evidence that would determine a village (multiple, contemporaneous dwellings) would almost certainly require excavations. Given that almost all native building materials were biodegradable, most of what would be left of a Native structures would be different colored dirt from rotted posts defining holes used in the building of structures, and hearths used for cooking. Middens, or trash deposits, are also tell-tale signs of habitation, and can give enormous amounts of information on the daily lives of the people then living here.

While much of this evidence may have been lost, it is surprising what survives, and it’s likely that Ypsilanti still sits atop substantial archaeology. Recently, an entire Tequesta village was uncovered right in downtown Miami, Florida during new construction. Much of the site will be saved and incorporated into the development. Often in archaeology, the very best decision is to let things be. However, developments like the ones proposed for Water Street, which could potentially destroy these remains, demand that -if we can’t protect the site- we do what we can to mitigate any destruction with a careful recording of what remains before it’s destroyed. This was enshrined in the Historic Preservation Act of 1966 which stipulated that any project receiving federal funds would be reviewed for potential impact on historic and archaeological resources.

MARK: As I noted on the site a few days ago, there were two relatively significant discoveries of what appear to be Native American burial sites on the property we currently refer to as Water Street. One was in 1901. The other was in 1914. What can you tell us about what was found, and what inferences, if any, can be drawn from these discoveries?

MATT: For all discussion of the location of the site, I think it’s important that we remain a little obtuse and say the cemetery was in the present Water Street Development site, and nothing too much more specific. In both cases, bodies, and what are assumed to be grave items, were discovered when gravel was being dug for a railway bed in the Water Street area. The site was publically looted after the bodies were uncovered, and many of the items went into private collections, or sat on Ypsilanti mantelpieces, and are now lost to history. Mark Jefferson, the emanant Geography professor at the Normal College, took pictures, collected items and made some notes. If there is any hope of tracking down further information on the cemetery it will be through Jefferson’s records.

The number of bodies and the amount of goods indicate a cemetery at the location. It would have been within eyesight, as every place was in this part of the Huron River, of the towering forty-foot bluff across the Huron that held a large number of mounds and burials, centered on where the Gilbert Residence now is, and extending north to Pearl Street. These mounds were probably earlier, and perhaps much earlier, burial sites than those found on Water Street area.

While it is entirely possible that the two sites are cemeteries of the very same people, the mounds may have been from a different (and unknown) culture to those whose graves were unearthed in the early 1900s. It is also possible that some of the earthworks and features on the bluff were misinterpreted as burial mounds and performed other functions.

We can only speculate on why the bodies were buried where they were, but it could well have been a reflection that the area was already considered “sanctified” by the earlier graves. Our culture has done the same thing; many early Christian cemeteries in southern Ohio were placed around ancient Indian mounds and include them as centerpieces in their layouts.

It should also be noted that the possible cemetery would have been close to the Potawatomi Trail, a main route from Lake Erie along the Huron River into the interior, and in close proximity to where we know Native settlements and the trading post were. Though, they may not have been contemporaneous with these.

MARK: What was found on the Water Street site?

MATT: Seven bodies were uncovered in 1901, and three more in 1914, with similar artifacts found with the bodies on both occasions. The items found, as described, are an exceptionally rich collection and point to a historic or proto-historic cemetery, making the most likely candidates Wyandot or Potawatomi, though it could be others. The fact that intact cloth was said to have survived (until it turned to dust when removed) also points to a later cemetery, perhaps one utilized by the last native group to live in Ypsilanti, the Potawatomi.

Some of the bodies were said to have been wearing beads about their necks and ankles. And some were buried with knives, tomahawks, projectiles, and, in one case, a soapstone pipe. The weapons would indicate the graves of men or warriors. If they are Potawatomi warriors, this would be significant not just for Native history, but for the regions history in the formation of the United States as well. Shells seem to be ubiquitous, and some could have come over vast distances.

Included with items that would be considered traditional, many metal ornamental items were discovered, indicating that this cemetery was well after Europeans began trading with Native Americans (though it would certainly be possible for a Native group to get these items without ever directly trading with Europeans). While it is not true that native North Americans worked no metal (they were among the first peoples in the world to mine and fashion copper), the metals described in the articles, except for the copper, would all have only been available after in post-contact America.

They include buckles, pots, silver ornaments, knives, utensils and an item that was said to have had “King of Spain” written on it, next to a “picture”. It’s not said if it was written in English or Spanish. If it were written in English that would be odd to say the least. It should be remembered that it was the Spanish who first traded with native North Americans and continued to have a presence in places like Missouri all the way until 1800. If we had that object, we could learn a great deal from it about trade, and help to establish a timeframe for the cemetery.

MARK: Given all of what we’ve discussed, would I be correct to assume that you’d like to see the City do more to recognize out Native American history?

MATT: Obviously, it’s not just Ypsilanti that needs to do more in this regard; the country has never approached coming to terms with this past. However, the myth developed over almost two hundred years of brave French traders and tenacious pioneers taming a wild and largely uninhabited land is not just factually false, but it’s rooted in the racist denial of the Native American birthright that allows their disenfranchisement to continue today. It’s not just a question of the past, but of the present, and the future.

The real story shows that everything, from the reason Ypsilanti is where it is, to why it was founded when it was, is entirely contingent on Native Americans and their history; a history which is still evident in the landscape of the City. The story of Ypsilanti is not just incomplete without this perspective, in fact it is false.

Ypsilanti owes the descendants of those removed an acknowledgement at the very least that there would be no Ypsilanti without a long history of Native American life on the Huron well before the first European set foot in Michigan, and the genocidal removal of those people who were already here. Furthermore, the descendants of those who called this place home are still very much alive and should be included in discussions as to how the City grows to view itself and rectify its past.

[Matt has kindly agreed to lead a walking tour of the Huron River in downtown Ypsilanti, talking about our Native American predecessors, as part of our May Day festivities. So, if you’d like to know more, please plan on joining us at 7:00 PM on May 1 at the Water Street Commons.]

37 Comments

Matt has indicated to me that he welcomes discussion on the points which have been raised, so, by all means, if you want to add something, or challenge something said above, please do.

I live on Summit St. on Godfrey’s property. Brandy’s (Ave. Liquor) sits on top of what was called the “Old French Cemetery” which could explain all the bad luck associated with that store. We had to put a new sewer in a few years ago. While digging up the old sewer we uncovered a number of bones which were identified as bovine. Since we live across the street from Maurers house (part of their house is Godfrey’s log cabin), we figure our property was his garbage lot. Being on the highest point on the west bank over looking the river I have always assumed the spot has been occupied by native Americans for centuries and that Godfrey and La Chamber settled down next to an existing native American community.

Looting graves is vile. No wonder the Water Street development is cursed.

It sounds like something out of a Steven King novel — a retirement home built on an Indian burial ground.

The talk of “Native curses” and cemeteries comes across as a racist throwback to Victorian era ignorance. The “curse” is capitalist development.

I love Nandewine Sippy. Is there any way to find out with some degree of certainty whether that was the name for the river, or the community that existed on the banks of the river where Ypsi now stands? Either way, I think we need to invest in some local signage.

Sorry if my comment came across as racist. It wasn’t intended that way. I can see how you might react negatively to my use of the word “curse”, but my point had less to do with the Native American haunting of Water Street, and more to do with karma. I was suggesting that when our European ancestors started jumping into graves and pulling out the teeth and beads of the death, they didn’t exactly win us any points with the powers that be.

Do I believe there’s an actual curse? No. Do I believe that our ancestors acted abhorrently to the point that we should be punished? Yes.

Maybe our city leaders could insist that the section eight housing complex planned for Water Street put a plaque somewhere.

Nottawaseppi was also the name given to the village in Calhoun County settled by the returning Potawatomi in the 1840s near Athens.

We have to remember that the village name is not, like with us, a geographical indication, but the indication of the village as a community. Wherever the village traveled it would be Nottawaseppi. The same was true of many native groups, for example the Shawnee had a number of towns named Chillicothe all in different locations, but they were the same village as it relocated.

This is a really great read. I would think something bigger than a plaque is needed. Like a protected few acres or something like that. ;)

Does anyone know if a cultural impact study of Water Street was done? If so, is it available online?

I wish you had taken Steve Pierce as seriously when he tried to share his scholarship on the white slaves brought to Ypsilanti against their will.

Anonymous–

Don’t worry, you probably just didn’t realize, that around here, one of the requirements of sounding like a liberal intellectual is to accuse others of being racist at every conceivable opportunity.

Oh, and don’t hold your breath for an apology. That is not how the game works. Wrongly accusing another person of being a racist is low risk and high reward FOR THE ACCUSER.

I was thinking that anonymous was referring to the movie Poltergeist.

The reason the “curse” comments are a problem is because these were real people, right here, engaged in real events with real consequences, not more than 200 years ago. If we are to understand our history and ever get a grip on how we got to where we are now, we have to shed the mysticism about the past, and this is no more true than with Native American pasts.

And more than that, these real people had real descendants who ARE still very much alive and living just counties away who could very well read these, maybe innocent or even well-meaning, but profoundly dismissive and ignorant comments. My rant.

Again, I thought he was referring to Poltergeist, or perhaps Pet Semetary.

I’m pretty sensitive to such things but I think that both works are far more problematic than the comment from anonymous and much more deserving of derision.

I am not singling out anonymous comment for derision and take it for granted that they meant to malice, and I’ve never read a King novel so can’t comment on that (though I did like The Dead Zone with Chris Walken). However, Google “Indian cemetery” and “curse” and see what that throws up, it’s utterly common and always obscures the past and the present in unhistorical and dehumanizing contexts. It has come up on this thread and the previous post on this topic. The reason Mark and I wanted to do this interview is precisely to give the peoples who occupied the banks along this river some real historical context and a sense that the decisions they made, not some myth of a curse, shaped Ypsilanti.

should say “no malice”!

OK, fair enough.

Thank you. This is the most comprehensive thing I’ve ever read on the subject.

I swear we have mounds on our property but the Mr. says it’s just a place where the river went around land. But why would the river go around land there and form mounds? At any rate, nobody is bothering them, so I suppose it’s neither here nor there.

Many thanks to Kristen C for posting this to Facebook. Anthropology focusing on modern native culture was my degree back in the day. I’ve been deeply interested to learn more about earlier Native culture in Ypsi — part of my love of local history in general. I’ve read several times that the name of the river for some culture was the Washtenaw. I believe Keewaydinokway, a native herbalist and UM grad from Garden Island (near Beaver Island) wrote that in her book. I also have a map of the Traverse City area with Ojibwe place names that points off the map to the Washtenaw River in SE Michigan. Any comments on the name Washtenaw and its relationship to the river, Matt?

So grateful to have this overview. Thanks for posting, Mark.

Lisele,

My understanding is that the word Washtenaw comes from the Ojibwe and means something like “the land beyond” or “the land over there”, which would be a perfect way of describing this area to people traveling here from the Detroit area where there would have been many Ojibwe speakers, including as guides. I have read other explanations, but this seems the most plausible. One of the difficulties with getting to the root of Indian names of areas is that they are almost always the European understanding of the words and how they were used. Just as today, a region can have multiple names meaning different things.

We might live in the United States, in the Midwest (or Great Lakes), in southeast Michigan, in the Greater Detroit area, in Washtenaw county, in the Huron Valley, on the Huron River in a town called Ypsilanti, on the west side in an apartment building called Tudor Manor on Normal Street which sits near the top of Summit Hill. All of those names (and more) could describe where we live depending on what we were trying to communicate and to whom.

Many more names (given the richness and variety of languages and cultures involved) would have described this area to Native Americans in the 1700s.

Another note on county names; a number of Michigan names we take for granted as being Native American, like Arenac or Oscoda, or Kalkaska or Leelanau (28 county names, all told), are completely made-up constrcuts in the mind of Henry Schoolcraft. Perhaps he thought he knew Natives Americans so well, he could make up words for them.

Wow. Those are all great thoughts. Wish I could do the southside tours, but I work on Saturdays, sadly. But perhaps the May Day tour is a possibility.

I loved your description of the great variety of names we use to describe the same place — and of course, you might also say, “i live in normal park,” since neighborhood associations are very important geographic boundaries in Ypsilanti (Nandewine Sippy).

Just read at Gizmodo:

A 4,500-year-old American Indian burial ground—one of the richest and best preserved found in California in the past century—has been paved over for a multimillion dollar housing development in the Bay Area. And archeologists are pissed.

One angry archeologist had this amazing quip in the San Francisco Chronicle, which broke the story.

“The developer was reluctant to have any publicity because, well – let’s face it – because of ‘Poltergeist,’ ” said [archeologist Dwight] Simons, referring to the 1982 movie about a family tormented by ghosts and demons because their house was built on top of a burial ground.

http://gizmodo.com/rare-indian-burial-ground-quietly-destroyed-for-million-1567902076

I had to put this somewhere.

Read more:

http://gawker.com/how-the-flaming-lips-lost-a-drummer-over-native-america-1570423161

Wayne Coyne is kind of douche. Ask Erykah Badu.

http://jezebel.com/5916667/erykah-badu-to-flaming-lips-frontman-kiss-my-glittery-ass

I lived on Tuttlehill Rd. in the 50’s, 6612 to be exact. There is a woods there, once part of the Ira Fuller Farm. There are Mounds near the back of the woods That I think should be looked at. It is close to the River. The Cosgrove Farm (6612) was also an Underground Railroad House. I tried to save it, but failed. I think the House might have been built by one of the Tuttle Bros. If you find anything I would like to know. good Luck.

Rev. Mr. Harvey C. Colburn penned, “The Story of Ypsilanti” to commemorate Ypsilanti’s Centennial in 1923; the 1920’s census report documents seven thousand residents dwelling in the historic East Side and around the outskirts Woodruff’s Grove pre-WWI.

Chapter One, the Wilderness Prelude describes the path of the glacier, mound builders and primitive Americans. Below are a few excerpts:

“The coming of the white man found him still in the rude hunter stage of existence, but skilled in certain barbaric arts, possessed of an interesting social life, and, along with his savagery, marked by some admirable qualities. His story, at least as idealized in romance and poetry, is of lasting interest to his white supplanters.”

“In 1851 the boys of Ypsilanti became enthusiastic over the unearthing of Indian relics and the homes of the village [extending along the west bank of the Huron River between Pearl and Catharine Streets] became archaeological museums.”

“In the month of April, 1680, the foot of the white man first pressed the soil of the future Washtenaw County.” This juncture in time marks the end of wigwam developments, the moccasin wearing pre-Ypsilantian and her culture without delay was discredited and replaced by “strange stories that have been carried by traveler’s gossip over unimaginable distances, quite incredible, surely, stories of strange men of pale complexion who wear clothing even when the sun shines most hotly…foolishly drive away game by cutting timber and making fences, and carry fire-sticks that explode with a loud bang, working swift devastation among their enemies.”

“The Story of Ypsilanti” (originally published in 1923) is available for rental at the Michigan Avenue YDL.

“,it’s not just Ypsilanti that needs to do more in this regard; the country has never approached coming to terms with this past. However, the myth developed over almost two hundred years of brave French traders and tenacious pioneers taming a wild and largely uninhabited land is not just factually false, but it’s rooted in the racist denial of the Native American birthright that allows their disenfranchisement to continue today. It’s not just a question of the past, but of the present, and the future.” (Well said, Matt!)

This Thursday night at 6:30 Matt will be presenting his research on Ypsilanti’s Native American history at the downtown library.

INFORMATION:

https://www.facebook.com/events/407562842741454

“Ypsilanti’s place on the Huron River was once the site of an eighteenth and early nineteenth century Potawatomi village in an area rich in evidence of a variety of Native American cultures.

Trails, mounds, cemeteries, village sites and fields dot the local landscape and are testimony to the different ways the landscape was seen and used over thousands of years.

In more recent times, from the founding of Detroit in 1701 to Tecumseh and the War of 1812, the peoples who called the Huron River the Nottawaseppi played a central role in the region’s history.

Many of the descendants of those Potawatomi continue to live in Michigan today.

Join local historian Matt Siegfried as we discuss Ypsilanti’s Native American landscape and the story of the peoples who lived here.”

W. B. Hinsdale died in 1942, and at least some of his notes and papers were donated to U of M’s Bentley Library. They are accessible there:

http://quod.lib.umich.edu/b/bhlead/umich-bhl-851538?rgn=main;view=text

I realize this is a year old, but I’m just finding this post. is there anywhere that artifacts from the ypsilanti/ann arbor/washtenaw county area are stored or on display?

I would love for the Washtenaw County History volunteers and museum communities to add this information to their website.

Fantastic read! Is there any additional information out there on the Native Americans that used to inhabit this area? I’d love to learn more!

Hi Mark, I’m a local musician and have written a song “The Beautiful Huron”. I describe it as a short cultural and environmental history of the Huron River. I am sending you the youtube link FYI. You seem to be diligently involved in our local history and I am reaching out to you as a history buff also. Please feel free to comment on it via my email address. If you know any non-profit organization who would be interested in featuring the song to benefit their relevant cause, you may be a conduit for that purpose. I have already presented it to the local Clean Water Action and Huron River Watershed Council. Peace and good health. The Beautiful Huron w subtitles – YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zjFJrdlOYG0

Posted a comment earlier and a link to a song I wrote about the Huron River. Please let me know you received it. Thank you.

10 Trackbacks

[…] 7:00 PM Our Local Native American History walking tour with Matt Siegfried […]

[…] just now, I was given a terrific opportunity to do just that when my friend, the local historian Matt Siegfried, posted the following two newspaper scans to the South Adams Street page he maintains on […]

[…] note: The above video, which features Ypsi’s Schultz Outfitters, was just recently produced by the Huron River Watershed Council as part of the RiverUp! campaign… And, if you’d like to know more about the history of the river, check out my recent interview with historian Matthew Siegfried. […]

[…] ago I received an email from a fellow by the name of Roger Pellar. He’d apparently read my interview with historian Matt Siegfried about Ypsilanti’s Native American past, and was hoping that, through this site, I might be able to help him identify a few artifacts that […]

[…] artists and makers. We live in a community where our local waters are getting cleaner. We live in a community rich with history. We live in a community full of thriving locally-owned businesses. We live in a community where […]

[…] the evening of December 1, our friend Matt Siegfried, who I interviewed here not too long ago about Ypsilanti’s Native American past, will be at the downtown branch of the Ypsilanti District Library, presenting his research on the […]

[…] with Matt’s work, here are links to two conversations that he and I have done in the past on Ypsilanti’s Native American past and the lives of former slaves in Ypsilanti. I think they should give you a pretty good idea of how […]

[…] guest, local historian Matthew Siegfried, who I’ve interviewed here on the blog before about Ypsilanti’s Native American past and the lives of former slaves in Ypsilanti. Our discussion was kind of all over the place. From […]

[…] Not only have I posted several dozen articles and in-depth interviews here about Water Street, it’s history, and the various twists and turns the development has taken over the years, but I’ve also […]

[…] the Native history of Dearborn, Flint (it’s literally named Flint), Detroit, Ann Arbor, and Ypsi. If you’re on the Ann Arbor campus, maybe check out this talking circle or similar […]