On the evening of December 1, our friend Matt Siegfried, who I interviewed here not too long ago about Ypsilanti’s Native American past, will be at the downtown branch of the Ypsilanti District Library, presenting his research on the role Ypsilantians played on the Underground Railroad. In hopes that it might inspire a few of you to go and hear Matt’s presentation, here’s a not-so-brief discussion between the two of us on the subject of slavery, the fight for emancipation, and the role played by Ypsilantians in that struggle. [Part 2 of our discussion will be posted later in December.]

MARK: I’ve heard it said several times since moving here that Ypsilanti was a somewhat significant stop on the Underground Railroad (UGRR), but I’ve never done the research to see what evidence, if any, exists… So I’m curious as to what you may have found in your research to support the claim that large numbers of escaped slaves made their way through Ypsilanti. Are there diary entries? Do interviews exist with people who were actively involved, or their descendants?

MATT: Yes, there is evidence. When you get right down it to it, though, the fact that a thriving black community existed in Ypsilanti prior to the Civil War is the single best piece of evidence we have.

MARK: So, if I’m interpreting your response correctly, you’re saying that all the evidence we really need to prove that Ypsilanti was a significant part of the Underground Railroad is the fact that we had a relatively significant black population during the period of time that the Underground Railroad was operating… the implication being that almost all black families at the time would have been engaged in the struggle to help get runaway slaves to freedom. Is that right?

MATT: Something like that. Given the context and history of the period, the fact that Ypsilanti had a large black population at the time is pretty compelling evidence that this area had strong associations with the black freedom struggle, yes. We are accustomed to view the Underground Railroad as the activity of heroic whites, so we tend to look for the evidence of the UGRR in the basements of well-heeled 19th century social reformers, rather than in the communities built by the actual passengers on that Railroad. (And why is it that it’s always basements that we’re looking in? Did no one hide in an attic?) But the stories of those white reformers doesn’t even scratch the surface.

MARK: As it’s white people who have been writing the history books, that’s not terribly surprising, is it?

MATT: No, and here’s a good example of historic whitewashing… In 1923, at the centennial anniversary of the founding of Ypsilanti, the heritage folks of their time, Daughters of the American Revolution-types, celebrated Ypsilanti’s role in the Underground Railroad by dressing a white family up in blackface and having them pretend to be slaves escaping to freedom. [See image below.] Meanwhile, the actual people who had escaped from bondage, and their descendants, lived just blocks away, on Ypsilanti’s segregated southside. To me, that says so much about the City’s past inability to recognize Ypsi’s black citizens and the circumstances that brought them here. It’s a genuine part of Ypsilanti’s history, and it should be known. I should add that Ypsi is not alone in this.

MARK: OK, so let’s talk about those early black families of Ypsilanti, and what we know about their involvement in the Underground Railroad.

MATT: Nearly every black family in Ypsilanti at that time would have been connected in some way to the UGRR and the movement against slavery, whether as passengers, activists, or as people who came to Ypsi from black refuge communities in either Canada or the Ohio River Valley.

MARK: These were black communities that grew up along the Underground Railroad?

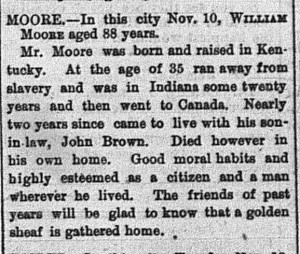

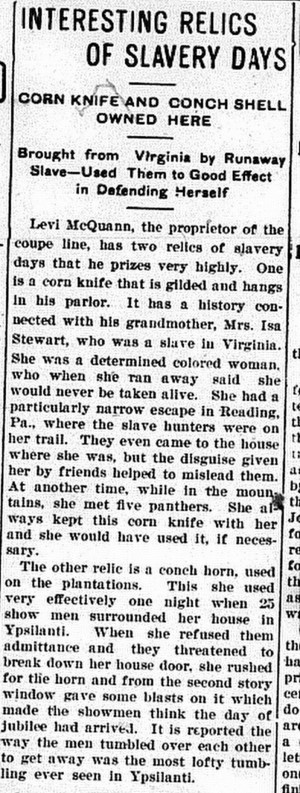

MATT: Yes. Any number of settlements in the region were founded as a result of the flight from slavery, and many Ypsilantians from that time, even if never fugitives themselves, would have spent time in these settlements. We know that through obituaries, newspaper accounts, census and death records, and the stories handed down by dozens of local families. [Pictured below is the November, 17, 1883 obituary of William Moore, who lived in the Stony Creek settlement of Randolph County, Indiana, and in Chatham, Ontario, before settling in Ypsilanti.]

MARK: So, we know that black Ypsilantians of the mid to late 1800’s often made their way here by way of these settlements that had evolved in concert with the Underground Railroad, as runaway slaves made their way northward…

MARK: So, we know that black Ypsilantians of the mid to late 1800’s often made their way here by way of these settlements that had evolved in concert with the Underground Railroad, as runaway slaves made their way northward…

MATT: Here’s what we know… In 1860, nearly two-thirds of all black people in Ypsilanti claimed to have been born either in Canada or in a slave state. (For comparison, the majority of whites at that time not born in Michigan would have come from New York State.) The 1860 census is also full of single, young black men working on area farms claiming that they were born either in Canada or places “unknown.” In 1870, these same men will claim birth in places like Kentucky (the largest place of origin of early black Ypsilantians) or Missouri. I think it’s safe to assume that these men were hiding the fact that they’d come from slave states, only admitting later, after the war, that they had been fugitives from slavery.

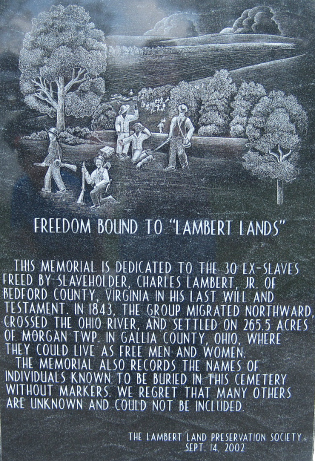

And, when I researched the histories of those black Ypsilantians who claimed to have been born in the north, mainly in Ohio and Indiana, I saw that nearly all were born in communities associated with the UGRR, like the Weaver or Lost Creek settlements in Indiana, or the Lambert Lands or Mt. Pleasant in Ohio. [Pictured right is the Lambert Lands historic marker.]

And, when I researched the histories of those black Ypsilantians who claimed to have been born in the north, mainly in Ohio and Indiana, I saw that nearly all were born in communities associated with the UGRR, like the Weaver or Lost Creek settlements in Indiana, or the Lambert Lands or Mt. Pleasant in Ohio. [Pictured right is the Lambert Lands historic marker.]

MARK: I know you’ve spent a great deal of time specifically looking into the ancestry of those black families living along South Adams Street at the turn of the century. Have you found that they lived in communities like the ones you’ve just mentioned, before settling here?

MATT: Of the twenty-two families living on South Adams Street, the center of black Ypsilanti for generations, in 1900, twenty-one were connected to the settlements set up in Canada for refugees. (These communities welcomed both fugitives from slavery and “free blacks” who were fugitives from racism.) Families routinely travelled from Ypsilanti to Buxton, and other Canadian settlements, for homecomings until well after World War II. In fact, some still do.

MARK: I’m curious as to what we know about specific individuals in Ypsilanti who were involved in the Underground Railroad. Can you give us a few examples?

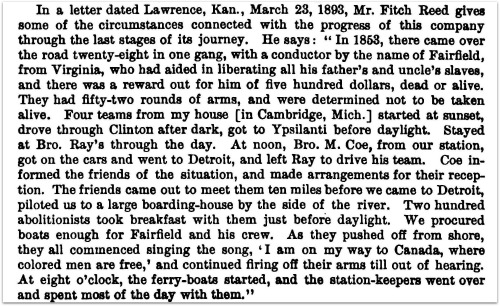

MATT: Well, there’s the compelling story of “Brother Ray” (Asher Aray), a black farmer living southwest of Ypsi, who led fugitives through Ypsi to Detroit, but most of the references are general. You’ll see phrases like, “through Ypsilanti,” “to Detroit through Washtenaw County,” and the like. [Seen here is an excerpt from The Underground Railroad (1898) by Wilbur Henry Siebert, which notes Aray’s work.]

MARK: As I’ve heard it mentioned so often, I suspect there’s also documentation of George McCoy’s work in this area, correct?

MATT: Yes. We know, through interviews with his daughter Anna, that George McCoy transported freedom seekers in a hidden compartment in his waggon from his Ypsilanti farm to Detroit and Wyandotte, beneath loads of cigars that he was taking to market.

MARK: Do any other specific examples come to mind of slaves who made their way through Ypsilanti, or the men and women who may have helped them here?

MATT: We know the story of Isaac Berry. A couple of years ago, I was honored to write the State Historical Marker for him and his wife Lucy, an interracial couple who ended up in Mecosta County. While writing the marker I was thrilled to see this reference to Isaac’s journey to freedom through Ypsilanti.

The following is from Negro Folktales in Michigan (1954) by Richard M. Dorson.

…Berry’s child related: He walked to Ypsilanti on the railroad. His shoes was all wore out, and his socks, and his feet got all swelled up, and his legs all swelled up. Sometimes when I think about it I want to cry, a human being getting treated that way. When he got to Ypsilanti he met a colored man going to work; he had his dinner pail with him. And he asked my father, “Are you a runaway slave?” And my father said, “It’s none of your business what I am.” He was wore out with people asking him questions. The other man said, “I can see from your shoes that you’ve come a long way. You see that house up the railroad a ways—that’s where I live. You go there and tell my wife to give you breakfast, and then you go to bed and stay there till I come home. I’ll be home at six o’clock.”

So he went on to the house, and the old lady took care of him, and he went to bed and slept all day—he said his feet and legs were so sore. He was walking three weeks. That night the house couldn’t hold all the colored people that came there. And they gave him carpet slippers and socks and took up a collection and gave him quite a lot of money. In the morning one old fellow took him down to the railroad and said, “You get a ticket for Detroit, and when you get there take a ferry to Canada, just about a mile across the lake, and then you’ll be under the lion’s paw.”

MARK: You’ve mentioned a few books by name, but I’m curious as to what other documentation is available to you and other researchers. Are there, for instance, local church records, or collections of firsthand narratives that mention Ypsilanti explicitly?

MATT: Abolitionist newspapers from the time, like the Signal of Liberty, the Anti-Slavery Bugle, and the Liberator all mention Ypsilanti and Ypsilantians. While not as important as nearby Adrian and Ann Arbor, white abolitionist activity in Ypsi is also recognized in dozens of clippings from the time which note meetings and speeches here. [The following clip comes from the June 30, 1893 Ypsilanti Commercial.]

MARK: What about organized efforts after the war to collect oral histories and the like?

MATT: In the 1850s, a number of abolitionist went on fact-finding trips to Canada. While there, they interviewed several people directly related to Ypsilantians, even a few people who lived in Ypsilanti themselves, and those stories are invaluable in tracing these stories.

Other works on fugitives in Canada, like Bound for Canaan, From Midnight to Dawn

, I’ve Got a Home in Glory Land

, and numerous local historical publications in Canada, mention families with Ypsilanti connections. It’s all a part of the same story… Even some of the men who sat with John Brown at his famous Chatham Convention before the raid on Harper’s Ferry had relatives in Ypsilanti.

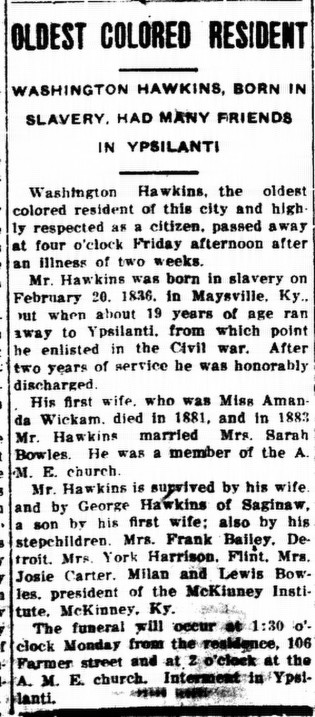

And there are thousands of hints in the obituaries and the stories that I’ve found through research. The same names and places keep coming up. In this case, the woods are easier to see than the trees, but you can still see the woods. [Seen below is the obituary of Washington Hawkins (August 7, 1915).]

MARK: Just to clarify, when you say that Ypsilantians were “connected to” these settlements that arose along the Underground Railroad, do you mean that they had family members in the settlements, or that they themselves had lived in these communities prior to arriving in Ypsilanti?

MARK: Just to clarify, when you say that Ypsilantians were “connected to” these settlements that arose along the Underground Railroad, do you mean that they had family members in the settlements, or that they themselves had lived in these communities prior to arriving in Ypsilanti?

MATT: In many instances they themselves had lived in these settlements before moving to Ypsilanti. Ypsilanti would have been an integral part of a single cross-border community for ninety miles or so on either side of the Detroit River. Families would have moved back and forth for decades, and Michigan and Ontario would have shared social organizations, churches, newspapers and cultural scene. In some ways, they still do.

Many of these families were free before the Civil War, and living in rural black enclaves like those in Gallia County, Ohio, or north of Madison. I’ve found several examples of families that lived next to each other in these settlements, like the Kersey and Artis families in Indiana, or the Richardson and Travis families in “Liberia,” Pennsylvania, then again living next to each other in Canada, only to be living next to each other again in Ypsilanti decades later.

MARK: What can you tell us about Kerseys, for example, and the journey that brought them here?

MATT: The Kersey family’s journey is telling, and would be similar to so many who came to Ypsilanti. It starts in a slave-state, then to settlements north of the Ohio River, then to Canada after 1850, and finally to Ypsilanti in the decades after the Civil War. Dozens and dozens of individuals and families made the same journey. [James H. Kersey pictured right, circa 1870.]

MATT: The Kersey family’s journey is telling, and would be similar to so many who came to Ypsilanti. It starts in a slave-state, then to settlements north of the Ohio River, then to Canada after 1850, and finally to Ypsilanti in the decades after the Civil War. Dozens and dozens of individuals and families made the same journey. [James H. Kersey pictured right, circa 1870.]

The Kersey family would have been, at least partially, free before the Civil War, and living in Georgia. By 1830 they had come to an abolitionist stronghold north of the Ohio River called Richland, which is in Jennings County, Indiana. There they lived in the same community as future leading Detroit black abolitionist George DeBaptiste. In the early 1850s the family moved to Canada and the refugee settlement in Colchester, before settling in Buxton (founded in the 1840s by the emancipated slaves of William King) in the 1860s. The Kerseys then came to Ypsilanti around 1880.

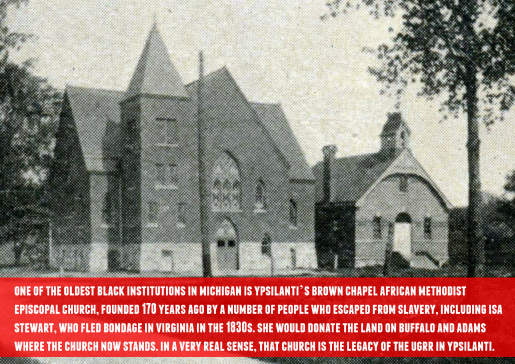

The Kersey family would have played a leading role in Buxton, Ontario. They were church deacons and built many of the homes there. In Ypsilanti, they would do the same. A number of homes still standing on on First Avenue and Second Avenue were built by James H. Kersey and family. Rolanda Kersey, now nearly 100 years old, still lives at the Kersey homestead on First Avenue, which has now in the family for over 120 years. Brown Chapel AME was said to be designed in the kitchen of the Kersey home. Built in 1904, the present church is the third AME church to be on the corner of Buffalo and Adams.

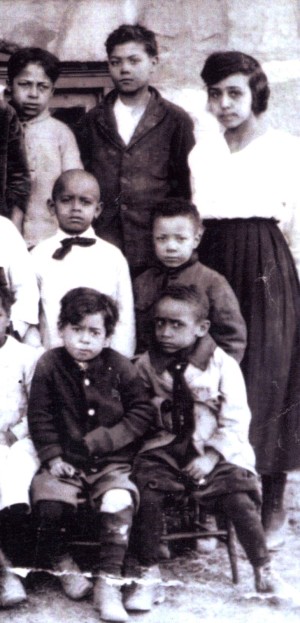

Bernice and Herman Kersey, siblings and children of James, would go on to lead the Ypsilanti schools desegregation campaign of the the 1910s. (This, by the way, would be reversed in the 1920s) and help found the city’s NAACP chapter in 1916. And Theron Kersey, great grandson of the generation that first fled the south before the Civil War helped found Eastern Michigan University’s AFSCME Local 1666. Today, there are dozens, if not hundreds, of Kersey descendants in the area. Do you see what I mean by connections? [Bernice Kersey can be seen to the right teaching at the South Adams Street School in February 1919. This the last class picture taken before the school closed.]

Bernice and Herman Kersey, siblings and children of James, would go on to lead the Ypsilanti schools desegregation campaign of the the 1910s. (This, by the way, would be reversed in the 1920s) and help found the city’s NAACP chapter in 1916. And Theron Kersey, great grandson of the generation that first fled the south before the Civil War helped found Eastern Michigan University’s AFSCME Local 1666. Today, there are dozens, if not hundreds, of Kersey descendants in the area. Do you see what I mean by connections? [Bernice Kersey can be seen to the right teaching at the South Adams Street School in February 1919. This the last class picture taken before the school closed.]

If you look at how the community came together and developed, a compelling picture is painted. One of the oldest black institutions in Michigan is Ypsilanti’s Brown Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church, founded 170 years ago by a number of people who escaped from slavery, including Isa Stewart, who fled bondage in Virginia in the 1830s. She would donate the land on Buffalo and Adams where the church now stands. Second Baptist was also founded before the Civil War, largely by people who had fled bondage to Ypsilanti. In a very real sense, these churches are the legacy of the UGRR in Ypsilanti. [A November 12, 1903 column from the Ypsilanti Daily Press on Isa Stewart’s escape from slavery can be found below.]

MARK: I probably should have started with this, but what was the operational structure of the Underground Railroad? Just how decentralized was it?

MATT: There was no single Underground Railroad, but many little railroads, each with their own particular story and dynamics. Which, in large part, is what made it so strong. There wasn’t one cohesive political group that could be targeted and destroyed. Most of the work was done ad-hoc, and often the people involved would have no idea of the work of other “lines” in the area. Many of the routes were based on personal relationships and were in a constant state of flux. Some were more established than others… Whole communities, as we’ve been discussing, were created in the environs of the Ohio River with the expressed purpose of helping fugitives. And many Ypsilantians, like those we’ve been talking about, came from those communities.

By and large, it was a hodgepodge of different activities directed against slavery, at many different levels, without anything like an overall operation or goals… As with any movement, it was beset by disagreements over strategy and tactics. There were many different trends, and those in the movement held different positions. And this was true on both the black and white sides of the movement.

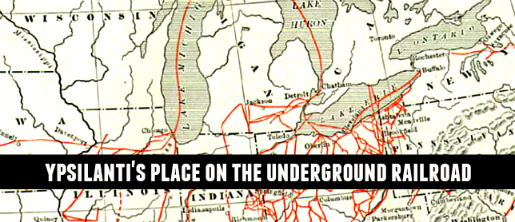

MARK: What do we know about the individual routes that ran through the area?

MARK: What do we know about the individual routes that ran through the area?

MATT: Again, routes would have come and gone. Some were well-connected and relatively public, like those of Levi Coffin and John Rankin. Others would have been the tightest held secret, long since lost to the grave. The routes certainly grew larger and more organized in the years leading up to the Civil War.

Detroit was, for obvious reasons, one of the most important routes to freedom in Canada and was teeming with secret black organizations like the African American Mysteries: Order of the Men of Oppression led by the remarkable William Lambert. I am sure that many of these organizations had relationships with black Ypsilanti at the time. Certainly the Prince Hall Masons were involved and they had an early chapter, Hart Lodge #10, here in Ypsilanti. (They’ve been in Ypsi 160 years, and on the same corner for at least 140 of those.)

They would not miss a beat and got right into organizing blacks to join the Union army in Michigan during the Civil War, which for many was simply a continuation of the struggle they had been engaged in for decades.

MARK: So, if there’s one big takeaway from today’s discussion, it’s that the black freedom movement was something that largely happened independent of white society…

MATT: Yes, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that a black freedom movement would, overwhelmingly, be the concern of black people. It involved, primarily, black participation in the freeing and shepherding of fugitives to freedom, mainly from states in the upper and border south to the north and, increasingly, to Canada.

Some fugitives got to freedom without any help at all. Indeed, the most important decisions, from that of whether and how to escape onwards, were made by the “passenger”. Passengers on the Railroad, contrary to the popular image of the fugitive shepherded from safe place to safe place, head down and silently being guided to freedom, were nearly always active participants in their own freedom.

Both ends of the railroad, the start and the finish, were embedded in the world of African America, and many of the “stops” and “conductors” along the way would have been folks most trusted by those fleeing, other black people with their own stories of slavery and freedom.

Conductors were often black, but whites, because of their obvious privileges, would often be of best aid on the UGRR playing that role. “Stations” were often in black communities, including rural hamlets. For some, the only station they ever slept in was their own camp.

Black Detroit was among the most organized northern African-American communities and the UGRR there was led by such people as George DeBaptiste, Rev. William Munro, and William Lambert. These men had both public and secret roles in the anti-slavery movement and would have been the most important activists, white or black, in the clandestine movement of people to Canada. Churches, like Second Baptist and fraternal organizations like the Masons in the city were also centers of organizing. Eventually, the operations run by the likes of Lambert would become well developed and rival any in the country. Ypsilanti’s large black community would naturally have been in their orbit.

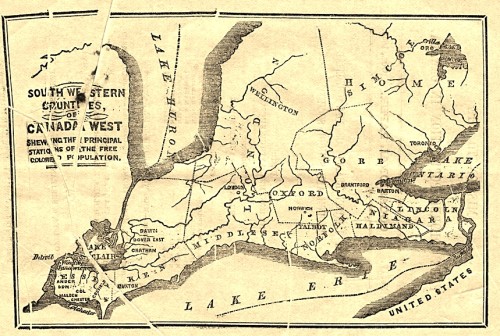

And finally, and this is what most don’t tend to think about when they think about the UGRR, but the terminals, the end of the line, invariably ended in a black community peopled by others who had made a similar journey. Without these towns, villages and homesteads there would have been no possibility of an Underground Railroad. Place like Chatham, Dresden, Colchester, Queen’s Bush, Buxton, Amherstburg, all places with deep associations with Ypsilanti. One can imagine how alive they would have been, with the freedom to self-organize in a way never they had before, with the debates of the time and the needs of the movement. [Below is a map of the Canadian West, showing the historically black communities being discussed.]

MARK: What were the politics like in these Canadian settlements?

MATT: In Canada, the debate was what kind of relationship to have with whites, if at all. There weren’t the “constitutional” versus “moral” divisions that cleaved white abolitionism. In some of the Canadian settlements, nothing short of a revolution was being called for. The idea of a slave revolt was appealing. It’s no accident that John Brown was drawn there in the hope of recruiting combatants for Harper’s Ferry.

Speaking of Brown, who was exceptional in many ways, I don’t want to diminish the role of white abolitionists. I hope I would have been one of them. But I think the generally held view of who was and was not an abolitionist has been far too skewed to white heros when the reality was very different. When we imagine an abolitionist, why do we almost never imagine the escaping slaves and the communities they created? Aren’t they practically abolishing their own slavery, and undermining the whole institution by doing so?

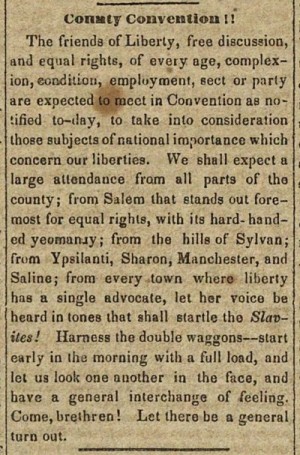

James Birney, Liberty Party leader and one of those white heroes, wrote in the late 1830s of what was not yet commonly known as the Underground Railroad, that “such matters are almost uniformly managed by the colored people.” [To the right is a September 17, 1842 clipping from the Liberty Party’s Signal of Liberty, announcing an anti-slavery convention to be held in Ypsilanti.]

James Birney, Liberty Party leader and one of those white heroes, wrote in the late 1830s of what was not yet commonly known as the Underground Railroad, that “such matters are almost uniformly managed by the colored people.” [To the right is a September 17, 1842 clipping from the Liberty Party’s Signal of Liberty, announcing an anti-slavery convention to be held in Ypsilanti.]

It should also be added that whites, always active in above-ground abolitionism, became increasingly active in the activities of the Underground Railroad as the crisis over slavery became widespread in the run-up to the Civil War. Ann Arbor had a host of public white activists, like the Beckleys and Richard Glazier, who would have been involved.

MARK: How did you get involved doing this kind of research, and what do you consider to be your most interesting discovery to date?

MATT: I’ve been studying local history through two degrees at EMU and there could be nothing more compelling to a local historian than Ypsi’s black history. It touches on all the crucibles on the 19th century… slavery and the fight against it, Reconstruction and its reverses. All that history is all around us, so it was natural for me to gravitate to it. I also have an interest as a historian in challenging national myths and conventional notions of the past, and, in America, that means race. So I think this story is significant for a variety of reasons, not least of which is the importance to the descendants of those historic black freedom fighters who now make up about a third of Ypsi’s people.

The most interesting discovery has been connecting the dots and seeing large historical movements embedded in the personal stories of folks. For example, when I find a family like the Ropers, I find them in Ypsilanti leading the struggle to desegregate the City’s Weurth Theater, which is still there, across from the Michigan Avenue Library, in the 1910s. And, in the 1880s, I find them living in Chatham, Ontario, the largest and most active refuge community in western Ontario, and the home of many Ypsilanti families. Before coming to Canada, the Ropers were living in a small Indiana community famous for being the home of one of the most active white UGRR activists of his day, Levi Coffin, who we discussed earlier. And before that, they were in the slave state of Virginia. A whole string of broad historical movements are embedded in their movements around the continent, and in their lives.

I also take some satisfaction in being able to trace families back into bondage. It’s very hard to find the history of most black families in the U.S. before emancipation, and I’ve been able to do that with a number of people. That journey has been illuminating and frustrating.

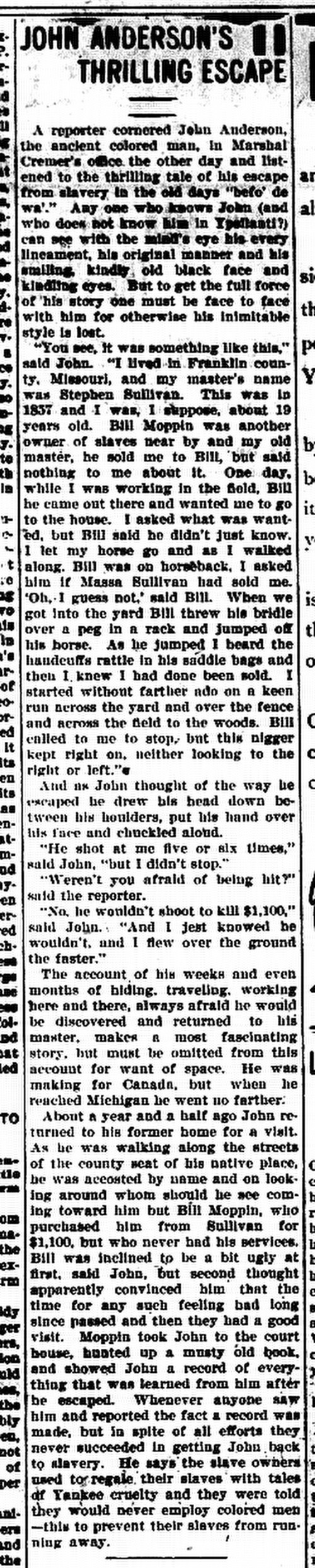

I also felt thrilled that a little historical justice was done when I found what happened to the Stephen Sullivan family, namesakes of Sullivan, Missouri, and “owners” of John Anderson. John lived at 303 South Adams in Ypsilanti for decades, having escaped slavery on the spur of the moment in the 1850s, when he thought he was going to be “sold down the river”. [John Anderson pictured right.]

I also felt thrilled that a little historical justice was done when I found what happened to the Stephen Sullivan family, namesakes of Sullivan, Missouri, and “owners” of John Anderson. John lived at 303 South Adams in Ypsilanti for decades, having escaped slavery on the spur of the moment in the 1850s, when he thought he was going to be “sold down the river”. [John Anderson pictured right.]

In his account, he was running as fast as he could, and could hear the bullets whizzing by him, but he wasn’t afraid, because he was worth “a thousand dollar to them and they wouldn’t dare shoot to kill.” They tried to get John back, but the Civil War intervened. Missouri was a border state and the Sullivans had their property confiscated because of their active support for Confederate guerillas in the war. That property included all their slaves. (Remember, the Emancipation Proclamation did not pertain to states, like Missouri, that were still in the Union.) Two of the Sullivan boys, who were fighting with pro-slavery guerillas, were killed by Union cavalry after refusing to surrender. And Anderson’s owner, Stephen Sullivan, died impoverished, a traitor, and bereft of children immediately after the War.

John, who made it to Ypsi before the war, and with a bounty on his head, lived through the war to be well into his seventies and saw many grandchildren born. He joined the 102nd USCT during the Civil War and his son Alfred would become the first leader of the NAACP in Ypsi in 1916. Yet another legacy of the Underground Railroad here in Ypsi. He is buried with a veterans marker in Highland Cemetery. The site of his grave is one of the stops I always make when giving tours of the cemetery.

[Following is John Anderson’s firsthand account of escaping slavery. It, according to Matt, is the only first person account he’s ever found of an Ypsilantian relating their escape from bondage. It ran in the Ypsilanti Commercial on January 25, 1901.]

UPDATE: Part II of this interview is now available.

17 Comments

Wow, this is great. One thing here in town that would be great would be a self-guided Underground Railroad tour, with a map.

Ypsilanti, however, is on the Adventure Cycling Underground Railroad bicycling tour route (Alabama to Owens Sound, ON) at http://www.adventurecycling.org/routes-and-maps/adventure-cycling-route-network/ugrr-detroit-alternate/ with a map of the route at http://www.adventurecycling.org/routes-and-maps/adventure-cycling-route-network/ugrr-detroit-alternate/#UGRR_Detroit_ALT_1detailModal

How about a fundraising campaign to set up a self-directed walking of Ypsi?

One wonders what these incredible men and women would make of Ypsilanti today.

For the record, my mother and I participated in the ‘Genome Project’ facilitated by the National Geographic Society at the Charles H. Wright Museum (fall 2009), and after receiving our results discovered that our ancestors never were freedom seekers, nor traveled along the Underground Railroad ways and trails. Ancestors migrated to America by way of Scotland as free men and women in the late 1870s. #mindblown #thoseslaveships tho’ #morecoffee

Thanks for the wonderful piece of JOURNALISM about the UGRR. Waiting anxiously for part 2.

I lived in the Gilbert Mansion for a number of years and it was always said that a bricked up door facing west into the hillside across from the railroad tracks was part of the UGRR. Escaping slaves entered and left from there and were housed in the basement between trains or something. I had the thought that it was a coal door, but…… who knows?

Keep up the good work.

An excellent interview chock full of information. Thank you Mark. Matt brings history alive; unburies the truth and lays it squarely on the table for all to feast. Loved it!

Chris Rock to Frank Rich today:

My mother tells stories of growing up in Andrews, South Carolina, and the black people had to go to the vet to get their teeth pulled out. And you still had to go to the back door, because if the white people knew the vet had used his instruments on black people, they wouldn’t take their pets to the vet. This is not some person I read about. This is my mother.

That’s an interesting note at the end of the Anderson article about him and his would-be owner meeting in the street years after the end of the Civil War. I would love to have witnessed that exchange.

What a wonderful, uplifting history lesson! Grateful for the interview; sorry I didn’t know of the presentation tonight in advance.

Pack a lunch when you visit this website because you can spend hours exploring and reading and learning about the history of Ypsilanti’s early African Americans residents and the South Adams Street communities where they lived, worked and worshipped. southadamstreet1900.wordpress.com

Really so great, Mark. Thank you. I wanted so much to get to the library for Matt’s talk tonight. Sincerely hope he does it again. What an exceptional post.

What about the white slaves who were brought to Ypsilanti against their will? Who tells their stories?

Thanks for a great article, Mark. So much rich history. I’m learning much about my family, the Morton’s, the Kersey’s of Ypsilanti.

My Great-Grandparents, Isaac and Lucy Berry, were mentioned in this article. Thank you for mentioning them. They certainly left their family an everlasting legacy of love and endurance.

Thank you again.

Thank you everyone for your interest in this very important historical research. I am a Caucasian female who stumbled onto DNA evidence that I have black ancestry. This made me very curious.

I traced my dna heritage and ancestors to Ypsilanti and am just diving into my apparently partially black heritage, which is very interesting. I don’t want To jump to conclusions, but my Grandmother’s grandmother was from Ypsilanti . She has an unknown place of origin but gave birth to several babies around 1845 – 1855 At the age of around 20 to 24 in Ypsilanti ;, then she changed her name and moved with one child to Elkhart Indiana. In Elkhart, she apparently changed the spelling of her first name and Married someone so that she had a different last name. I have a photograph of her and she looks like she has African-American heritage and she is the only one in my ancestry line who could explain my DNA black heritage

Based on my in-depth genealogy research, this great great grandmother didn’t have a known maiden name or birth Certificate.

I have a photograph of her and she looks like she is black or has black ancestry. given the Circumstances including The DNA evidence that I have african-American ancestry, in her photograph she looks at least partially black, the fact that her background is untraceable and there’s no birth certificate to be found ( unlike my other ancestors ), she spelled her name differently as she moved around and she had a daughter who is married and never mentioned her parents’ or mothers identity in the official documents., Could she could be potentially an escaped slave?? No official legal documents regarding her date of birth, marriage or death, and she had ties to places that were abolitionist communities.

Thank you for any thoughts or feedback on this

I would like to get in touch with Matt Siegfried. My great-grandfather’ father was a escaped slave whose story is told by the Raisin Valley/Institute abolitionist Laura Haviland. Through years of research, I have a long, detailed-filled story of the escape, additional escape attempt, and outcome.

4 Trackbacks

[…] past November, I posted a lengthy interview with local historian Matt Siegfried about slavery, the fight for emancipation, and the role played by Ypsilantians in that struggle. We covered an incredible amount of ground, but, as I still had a lot of unanswered questions, I […]

[…] and the passion that she has for our community. And Matt Siegfried was nominated for his work documenting Ypsilanti’s historic black community. The list goes on and on. And it wasn’t just the kinds of folks that you’d expect to […]

[…] two conversations that he and I have had in the past on Ypsilanti’s Native American past and the lives of former slaves in Ypsilanti. I think they should give you a pretty good idea of how knowledgeable he is about this odd, little […]

[…] who I’ve interviewed here on the blog before about Ypsilanti’s Native American past and the lives of former slaves in Ypsilanti. Our discussion was kind of all over the place. From the University of Michigan’s […]