This past November, I posted a lengthy interview with local historian Matt Siegfried about slavery, the fight for emancipation, and the role played by Ypsilantians in that struggle. We covered an incredible amount of ground, but, as I still had a lot of unanswered questions, I asked him back. Following, as Paul Harvey would say, is the rest of the story. In today’s installment, Matt and I discuss the ramifications of the Fugitive Slave Act, the activities of slave-catchers in Michigan, the bravery of local abolitionists in the face of violence, and the remarkable life of HP Jacobs. I hope you find it as fascinating as I do.

MARK: Given the amount of Underground Railroad activity this side of the border with Canada, my assumption is that, in addition to escaped slaves, Ypsilanti likely also saw its share of slave hunters in the wake of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which gave southern slaveholders the right to send agents into free states in order to retrieve runaway slaves.

MATT: In general, I think that the danger posed by slave-catchers, with a few exceptions, diminished the further one got from the south. For example, violence to recapture slaves would be much less tolerated in Michigan than in southern Ohio, or Kentucky for that matter. Not only were the politics different the further north you went, but this was an era before there was a pervasive communications infrastructure in place, so the search for runaway slaves became more difficult with each mile… That said, Detroit, for obvious reasons, would have been a hive of such activity, and the city saw a whole economy grow up around slave-catching.

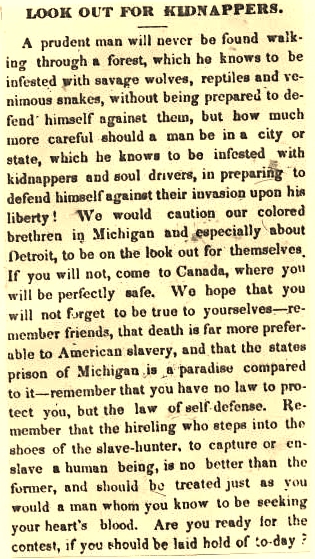

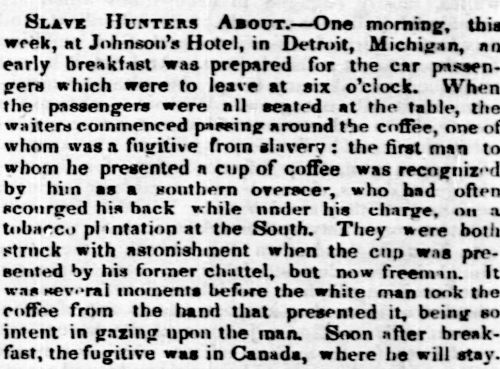

In 1855, under pressure from a growing anti-slave power movement (one could be opposed to slave power, without being opposed to slavery, one could be opposed to slavery and still be virulently racist), Michigan passed ‘personal liberty laws’ that attempted to restrict the impact of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act. [Right: Voice of the Fugitive, April 23, 1851]

In 1855, under pressure from a growing anti-slave power movement (one could be opposed to slave power, without being opposed to slavery, one could be opposed to slavery and still be virulently racist), Michigan passed ‘personal liberty laws’ that attempted to restrict the impact of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act. [Right: Voice of the Fugitive, April 23, 1851]

MARK: What do we know of the activities of slave-catchers in Detroit?

MATT: There were constant battles, both in the courts and in the streets, against the activities of slave-catchers. At one point, the city proposed to build a special jail for runaways, to the outrage of abolitionists, who found the idea of a “slave-pen” in Michigan to be abhorant.

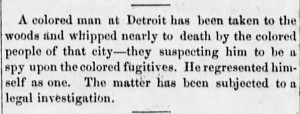

It was a dangerous business, a matter of life and death, and there are a number of accounts of blacks who were accused of betraying fugitives being the subject of some rough justice by Detroit’s black community.

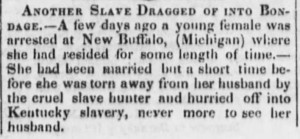

Detroit’s white community was, with a few notable exceptions, notorious for being hostile to blacks and the activities of the Underground Railroad. The Detroit Free Press was the go-to paper of white reaction at the time. While there were certainly white supporters, abolitionism did not enjoy anything like the support it did in places like Ann Arbor, or Adrian, or Ypsilanti. Also remember that in 1840, Detroit’s population is not yet 10,000… larger than Ypsi’s at the time, but there was nowhere near the difference in size between the two communities that we see today. [Right: Anti-Slavery Bugle, October 1, 1853]

Detroit’s white community was, with a few notable exceptions, notorious for being hostile to blacks and the activities of the Underground Railroad. The Detroit Free Press was the go-to paper of white reaction at the time. While there were certainly white supporters, abolitionism did not enjoy anything like the support it did in places like Ann Arbor, or Adrian, or Ypsilanti. Also remember that in 1840, Detroit’s population is not yet 10,000… larger than Ypsi’s at the time, but there was nowhere near the difference in size between the two communities that we see today. [Right: Anti-Slavery Bugle, October 1, 1853]

MARK: Are there stories of slaves being apprehended in Ypsilanti and taken back south?

MATT: Not from Ypsilanti that I am aware of. Ypsilanti and the surrounding area, though, would have certainly been known to slave-hunters, and we have hints from a few places of their activities. By and large, the movement in Michigan was pretty successful in resisting such returns, though.

MARK: Is there a specific Ypsilanti story that comes to mind?

MATT: The best-known story from Ypsilanti is one related by Laura Haviland. Haviland, a Quaker who would come to live near Adrian, on the Raisin River, was a pioneering Michigan abolitionist who helped form the State’s first anti-slavery society, The Logan Female Anti-Slavery Society, in 1832. Leaving the Quakers because her abolitionism was too radical, she established the Raisin Institute in 1836; a school open to all races, genders and creeds. A number of recently emancipated people were sent to the school, and the community that grew up around it was a hub of Underground Railroad (UGRR) activity. Haviland herself became increasingly involved in the UGRR after the death of her husband. She really is an amazing woman. Her memoir, A Woman’s Life Work, is available online for free, and well worth reading for those interested in the history of the UGRR.

MARK: And, according to Haviland, what happened in Ypsilanti?

MATT: Well, in her memoirs, she relates the story of slave-catcher Thomas Chester, son of slave-owner John P. Chester of Tennessee, who came to Ypsilanti in 1850 looking for the family of Willis and Elsie Hamilton, who had escaped from Nashville all the way back in 1832. Haviland had helped the Hamiltons years before. Among other things, she had traveled south in 1846 to try and rescue the Hamilton’s children. She had many tangles with the Chester family, including them putting a gun to her face once in Ohio.

So this slave-catcher and his posse took rooms in an Ypsilanti hotel and began observing the black population in the City, and the surrounding area. They did this for an entire month. And, when they thought they had the right people, a witness was summoned who then verified it in the court of Detroit Judge Ross Wilkins. Wilkins was an abolitionist sympathizer, but he did what was required of him under the law… All it legally took for a warrant, at that point, was the say-so of the slave owner. [Right: Image from Haviland’s memoirs]

So this slave-catcher and his posse took rooms in an Ypsilanti hotel and began observing the black population in the City, and the surrounding area. They did this for an entire month. And, when they thought they had the right people, a witness was summoned who then verified it in the court of Detroit Judge Ross Wilkins. Wilkins was an abolitionist sympathizer, but he did what was required of him under the law… All it legally took for a warrant, at that point, was the say-so of the slave owner. [Right: Image from Haviland’s memoirs]

Unbeknownst to Chester, though, and Haviland for that matter, the Hamiltons had gone to Canada in the late 1840s. So the individuals he’d identified weren’t the Hamiltons.

MARK: Had the Hamiltons escaped from the Chesters, or was Thomas Chester, in this instance, acting as a freelance slave-catcher on behalf of another Tennessee slave-owner?

MATT: The Hamilton’s had escaped from the Chesters. Thomas Chester was the lawyer son of John P. Chester, the slave-holder. The Chesters were businessmen, including the business of slavery, from Jonesboro, Tennessee. Looking at the slave schedules, which counted the enslaved concurrent with the Federal Census in order to determine white Congressional representation, they owned around a half dozen people, which would have made them moderately wealthy on the slave-owning scale, and very wealthy when compared to most folks.

MARK: So, what happened after Chester got the warrant in Detroit for the people he thought to be Willis and Elsie Hamilton?

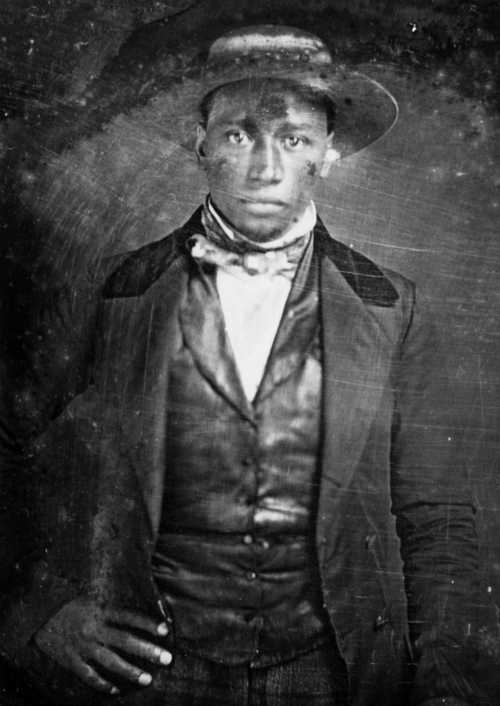

MATT: Well the Chesters had bad a reputation, and Judge Wilkins sent word to leading black abolitionist George DeBaptiste about the danger the “Hamiltons” were in. According to Haviland’s narrative, DeBaptiste telegraphed a “vigorous worker” in Ypsilanti’s black community and runners were sent in “every direction” to look for the Hamiltons. When they couldn’t be found, it was determined that they must be well-hidden, and these runners went to the train station to wait for the slave-hunters. Their plan was to follow them, and do what they could to help protect their targets. [Below: George DeBaptiste circa 1846, at approximately 30 years of age]

MARK: And who were the targets?

MATT: The family that Chester had targeted was that of a man named David Gordon, who was, in fact, a free man. By the time Chester had arrived at their home, there was a crowd following him. Chester confronted Gordon and his wife, and they responded by showing their “freedom papers” from Virginia. At that point, according to the story, Thomas Chester put his gun to the heads of David’s wife and daughter, demanding they admit to being the Hamiltons. They refused, and the officers who had accompanied Chester, having found the papers to be legitimate, freed the Gordons. Spurned even further, Chester then attempted to arrest another black man on the way to the train as Willis Hamilton. At this point an officer is said to have told him, “You know not what you are about, I will arrest no man at your command.”

MARK: An amazing story that could have had a much less happy outcome…

MATT: Yes. If Chester had gone to a different judge, or if witnesses hadn’t been present, it could have been tragic…

MARK: What happened to the the Gordons, and Thomas Chester?

MATT: The Gordons would leave for Canada, and the Chesters would get a southern Congressman to accuse the Judge of being “allied with Mrs. Haviland of the interior of the State of Michigan, a rabid abolitionist, in keeping slaveholders out of their slave property.” This was said in Congress, in an effort to get Judge Wilkins removed from the bench. The effort ultimately failed. (The rich used Congress then just as they do today.) The Chesters’ feud with Haviland would last for years. It’s a particularly interesting story because we not only have Haviland’s version, but we have a letter published by Thomas Chester in 1851, in which he explains his side. Unfortunately, though, we do not have the account of the Hamiltons or the Gordons.

According to Haviland’s memoirs, John P. Chester, the Hamilton’s owner, would go on to become a slave patroller in the years before the Civil War. Ultimately, he would be shot dead by a black man of whom he demanded papers. That man would go on to be hung. Thomas Chester saw his father die and would go on to die himself a few months later of fever.

Again, we know everything about this case because of its association with one of the most well-connected and public figures of Michigan abolitionism. There very well may have been other cases in Ypsilanti. One would hope they all ended as positively. The whole story gives some indication of how difficult it was to implement the Fugitive Slave Act in some areas, and the inherent dangers to the entire black community in the wake of the Act.

MARK: You mention that Chester published his own account of what transpired in Ypsilanti. How does his account differ from that relayed secondhand by way of Haviland?

MATT: It’s different in many respects. It’s main focus is on the inability or refusal of Northern law officers to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act. Chester makes no mention of the fact that he got the wrong people and that he threatened them. He simply states that the Hamitlons were ferried to Canada before he arrived because the local black population was tipped off by the Judge. He ends it by making an appeal to those who have lost their “property” in Michigan to capture it “by force rather than expose themselves to the treachery of their officers or people.”

MARK: What about other stories concerning the lives of former slaves in Ypsilanti? Are there any folks that we didn’t talk about last time that you think people should know about?

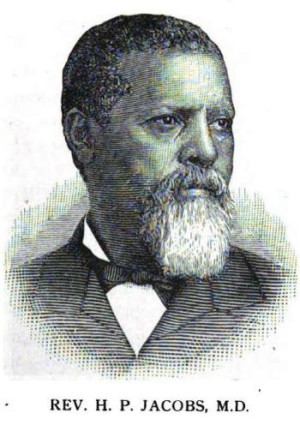

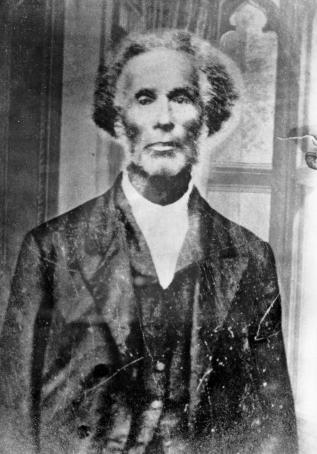

MATT: A name that must be mentioned is HP Jacobs, born into slavery in Alabama as Samuel Hawkins. He learned to read and write and forged freedom papers for his extended family. They left Alabama on July 24, 1856 and arrived in Canada on August 19th. There he was baptized by Rev. William Troy and shed his slave name, taking the name of HP Jacobs.

MATT: A name that must be mentioned is HP Jacobs, born into slavery in Alabama as Samuel Hawkins. He learned to read and write and forged freedom papers for his extended family. They left Alabama on July 24, 1856 and arrived in Canada on August 19th. There he was baptized by Rev. William Troy and shed his slave name, taking the name of HP Jacobs.

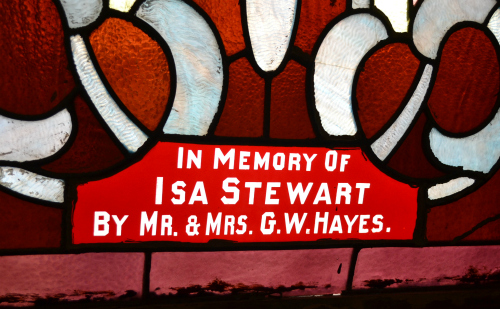

He then came back to Ypsilanti in the late 1850s and worked as the janitor for the Normal College (now EMU). While here, HP Jacobs founded Second Baptist, still active over 150 years later, and became its first pastor. Both black churches here, Second Baptist and Brown AME, were founded by fugitives from bondage and would have undoubtedly been deeply involved as their Detroit sister churches were, in the struggle for freedom. The stained-glass windows at Brown AME commemorate some of those very freedom-seekers, and are, in my opinion, among the most important historic treasures in all Ypsilanti.

[note: Our discussion of Isa Stewart can be found in part one of this interview.]

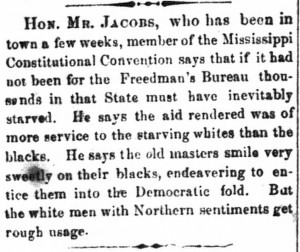

MARK: I’d never heard of Jacobs. What else can you tell us about him?

MATT: Well, he also helped to organize a school for Ypsilanti’s black children. His was the most prominent black voice in Ypsilanti during the Civil War period, leading marches, organizing rallies and speeches and participating in the statewide 1863 Michigan Colored Men’s Convention held in Ypsilanti. He may well have been active in the Underground Railroad, for he was connected to many of the most militant leaders in Detroit through the Baptist Church and 1863 convention, and as he was a veteran of the road himself.

He enrolled his daughters in the Normal (blacks could always study at the Normal) and his daughters (and granddaughters) would become the most celebrated area musicians of their day. When they graduated in their early teens, he took the family to Natchez, Mississippi. There he founded the Natchez Seminary, a school for recently freed slaves, which is now known as Jackson State University.

He would be elected to the Mississippi State Senate twice and Natchez City Council during Reconstruction… from slave to Senator in ten years. He helped to rewrite Mississippi’s constitution so it could be readmitted into the Union. He was also founder and first President of the Missionary Baptist Convention, the state’s first black Baptist authority. His children would later return to Ypsilanti and live here for decades at the center of black social life. His daughters, and this is the 1870s, would retain their maiden names, hyphenating Jacobs with their husbands’ surnames. Anna Jacobs-Dehazen taught music from her front room on South Adams Street.

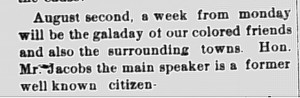

HP Jacobs would travel the country, often returning to Ypsilanti to visit his family and speak as an honored guest at Emancipation Day, the generations-long celebration Ypsilanti held on August 1st in conjunction with other black communities. Nothing underlines Ypsi’s role in the freedom struggle like Emancipation Day, which would sometimes bring thousands of people in the City. [Right: Ypsilanti Commercial, July 23, 1886]

HP Jacobs would travel the country, often returning to Ypsilanti to visit his family and speak as an honored guest at Emancipation Day, the generations-long celebration Ypsilanti held on August 1st in conjunction with other black communities. Nothing underlines Ypsi’s role in the freedom struggle like Emancipation Day, which would sometimes bring thousands of people in the City. [Right: Ypsilanti Commercial, July 23, 1886]

Late in life, he left the church and got his medical degree, becoming a doctor for black migrants out west. Recently, there has been a move to rename Jackson State University after him. There are dozens of Ypsilanti newspapers articles from the period which mention him, his activity and role. This was the one-time janitor at EMU… and perhaps the most important black man to ever call Ypsilanti home.

As a historian, I want to know what happened between then and now to bring us to a point where, today, no one in Ypsilanti knows him, the most important black Ypsilantian of the era.

MARK: I’ve heard you say before that there’s evidence that many living here prior to the Civil War were living somewhat openly as runaway slaves. Just how open were they? And should this be taken as evidence as to just how anti-slavery Ypsilanti’s white community at large may have been at the time? I mean, if there really were men and women living openly as escaped slaves, wouldn’t it have been fairly easy for people to have turned them in for a reward? [Right: Ypsilanti Commercial, September 26, 1869]

MARK: I’ve heard you say before that there’s evidence that many living here prior to the Civil War were living somewhat openly as runaway slaves. Just how open were they? And should this be taken as evidence as to just how anti-slavery Ypsilanti’s white community at large may have been at the time? I mean, if there really were men and women living openly as escaped slaves, wouldn’t it have been fairly easy for people to have turned them in for a reward? [Right: Ypsilanti Commercial, September 26, 1869]

MATT: I don’t think anyone advertised that they were an escaped slave, though there are more than a few cases of people flaunting it once they got to Canada. That said, I was surprised to see people living and acting quite openly in the period who clearly, or most probably, were fugitives from slavery. There are many examples in Ypsilanti; the Bowles, the Andersons, the Hamiltons, the Stewarts, the Jones and the Hawkins, to name a few.

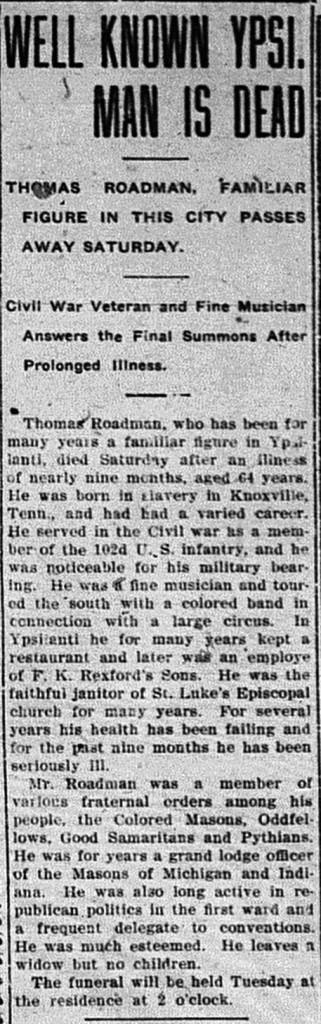

That doesn’t mean they were living openly as escaped slaves though. It’s also true that there were many ways to emancipation in individual cases. We know, for example, that some fugitives in the north ended up purchasing their freedom from their former owners, thereby making their emancipation legal. Others were freed by way of wills or other agreements. So, it’s also possible that a number of people we’re seeing in the historic record, who appear to be runaway slaves, were emancipated after having fled slavery. [Right: Ypsilanti Sentinel, April 26, 1909, Thomas Roadman obituary]

That doesn’t mean they were living openly as escaped slaves though. It’s also true that there were many ways to emancipation in individual cases. We know, for example, that some fugitives in the north ended up purchasing their freedom from their former owners, thereby making their emancipation legal. Others were freed by way of wills or other agreements. So, it’s also possible that a number of people we’re seeing in the historic record, who appear to be runaway slaves, were emancipated after having fled slavery. [Right: Ypsilanti Sentinel, April 26, 1909, Thomas Roadman obituary]

As for the threat of being turned in by white Ypsilantians, it wasn’t a situation where you could just turn any black person in. Slavery was held together by the legal system, and, as such, was bound up in all kinds of laws. Individuals had to be wanted, and there had to be a warrant for there to be any bounty offered. Of course, there were personal bounties and black markets as well. And some areas, like southern Illinois, and Indiana, and even Detroit and New York City, had judges and sheriffs who were just as supportive of slavery, and hostile to fugitives, as anywhere in the deep South.

Remember, many merchants and banks in the North were deeply dependent on the slave economy and would have been strongly against any threat to that relationship. So, you can see how the Fugitive Slave Act would have accelerated latent political, even social, differences in communities across the North.

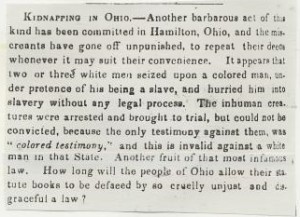

MARK: By “black market,” are you referring to the practice of kidnapping free blacks in the north and selling them into slavery?

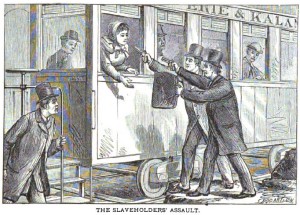

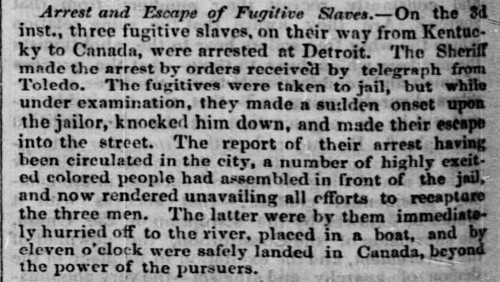

MATT: Yes, this certainly existed. Some may have seen the recent movie based on Solomon Northrup’s book. That world is not made up. There was a huge “black market” in slaves, including from Africa. We often think that it was the labor of the enslaved that masters were after, but this was a business; it was the value of the enslaved themselves in which the most wealth was held, hence such exertions to get those fugitives returned. Their bodies, not their labor, were worth hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars in a marketplace as thoroughly capitalist as ours is today. Indeed, nearly 20% of the entire nation’s wealth at that time, 3 billion dollars worth, was counted in human chattel. Once into the black market, it was an easy entrance into the legal market, and you are quickly lost. [Right: The Colored American, May 22, 1841]

MATT: Yes, this certainly existed. Some may have seen the recent movie based on Solomon Northrup’s book. That world is not made up. There was a huge “black market” in slaves, including from Africa. We often think that it was the labor of the enslaved that masters were after, but this was a business; it was the value of the enslaved themselves in which the most wealth was held, hence such exertions to get those fugitives returned. Their bodies, not their labor, were worth hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars in a marketplace as thoroughly capitalist as ours is today. Indeed, nearly 20% of the entire nation’s wealth at that time, 3 billion dollars worth, was counted in human chattel. Once into the black market, it was an easy entrance into the legal market, and you are quickly lost. [Right: The Colored American, May 22, 1841]

MARK: So black citizens of Ypsilanti, even though the situation may be described as relatively safe at the time, could never really let their guard down, as they could, say, in Canada.

MATT: I would think that as long as your status was unresolved, any fugitive could never afford to let their guard down. And this would have been especially true after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act. You know, it’s not something we often think about, but the psychological trauma of slavery, escape, and the fear of recapture, must have been really intense and damaging. Some folks may never have been able to let their guard down again.

The Act greatly increased the danger, and added to the general feeling of hostility, for all black folks living here. Whole communities, including many that we have talked about, uprooted from Ohio and Indiana and left for Canada at this time. Many thousands fled. For every one that stayed in Ypsi, someone probably left to go to Canada. We know that Second Baptist in Detroit lost many of their parishioners in this period. [Below: William Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator, March 4, 1852]

MARK: How did the Fugitive Slave Act change the operation of the Underground Railroad?

MATT: It had a huge impact. In addition to forcing entire communities to Canada, those involved in the freedom struggle began to force the issue at every opportunity. Slavery, as a result of the Fugitive Slave Act, had become an increasingly disruptive topic of concern in the North. What was before almost exclusively the work of black people, both required and spurred more white participation after the Fugitive Slave Act and the Dred Scott case.

MARK: What would have happened to a Michigan family caught harboring runaway slaves during this period?

MATT: Black and white families would have faced an entirely different measure of justice. The Fugitive Slave Act stipulated up to six months’ imprisonment and a $1,000 fine for helping a fugitive. The Act made the arrest of any black person obligatory on as little as the word of the former owner. In addition, it gave bonuses, or bounties, for captured slaves, giving multiple financial motives for the capture of black people, “free” or fugitive.

The Act compelled all states to enforce the ‘property rights’ of owners, and all citizens were obligated to aid in the fugitive’s return. Further, after the Dred Scott case (litigated in part for the slave owner by Ypsilantian Lyman Norris in 1857), blacks were confirmed to be non-citizens and had “no rights any white man was bound to respect.” They could not testify in their own defense; the slave-catcher’s word was all that was legally required. So, a black family would have been at risk from slave-catchers whether they had ever been enslaved or not. Both free blacks and fugitives were at risk after the Act, even before Dred Scott. And we know that fugitives were returned to the horrors of bondage from Michigan. [Right: Anti Slavery Bugle, January 10, 1852]

The Act compelled all states to enforce the ‘property rights’ of owners, and all citizens were obligated to aid in the fugitive’s return. Further, after the Dred Scott case (litigated in part for the slave owner by Ypsilantian Lyman Norris in 1857), blacks were confirmed to be non-citizens and had “no rights any white man was bound to respect.” They could not testify in their own defense; the slave-catcher’s word was all that was legally required. So, a black family would have been at risk from slave-catchers whether they had ever been enslaved or not. Both free blacks and fugitives were at risk after the Act, even before Dred Scott. And we know that fugitives were returned to the horrors of bondage from Michigan. [Right: Anti Slavery Bugle, January 10, 1852]

MARK: Are there instances of communities, either white or black, rising up to interfere with the activities of a slave-catcher in Michigan?

MATT: There were a number of cases. The two best known Michigan cases are those of the Crosswhite and Blackburn families, in which attempts were made to return fugitives to slavery only to face community resistance (black and white). Both of those cases happened years before the the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850 and demonstrate that the danger was real even before that time. Detroit had instances of blacks liberating those fugitives being held in City jails and saw a great deal of militant, street-level activity. There would have been “Vigilance Committees” in Detroit’s black neighborhoods that patrolled around the clock looking out for “soul-stealers”. [Below: The Liberator, June 11, 1852]

MARK: I’m not familiar with the Crosswhite and Blackburn cases. What happened?

MATT: The Blackburn case happened in Detroit in 1833 and involved Thornton and Ruthy Blackburn, who had escaped from Kentucky and settled in Detroit. When they were tracked down by their former owner, they were placed in jail awaiting return to the South. Detroit’s local black population, small at the time, organized Lucy’s escape by switching a free person with her while in jail. Then, 400 people stormed the jail to rescue Thornton. The resulting riot lasted for two days in Detroit, as Thornton made his way to Canada. There is a wonderful book, I’ve Got a Home in Gloryland, that tells this story. [Below: Thornton Blackburn’s wanted poster]

The Crosswhite case involved the family of Adam and Sarah Crosswhite, also fugitives from Kentucky, who had settled near Marshall, Michigan. When slave-catchers tracked them down in the winter of 1847 a large crowd of black and white came out to defend them. The crowd forced the sheriff to arrest the slave-catchers rather than the Crosswhites. As the slave-catcher’s legal situation was being resolved, the Crosswhites escaped to Canada. They would later return to Marshall. [Below: Adam Crosswhite]

By the way, the daughter of the Crosswhites, Sarah, married Ypsilanti Civil War veteran Lafayette Crosby and lived on First Avenue for decades. Together, they have a great many descendants in the Ypsilanti/Ann Arbor area. If your last name is Simmons, or Crosby, or Evans, you may be related.

By the way, the daughter of the Crosswhites, Sarah, married Ypsilanti Civil War veteran Lafayette Crosby and lived on First Avenue for decades. Together, they have a great many descendants in the Ypsilanti/Ann Arbor area. If your last name is Simmons, or Crosby, or Evans, you may be related.

MARK: I didn’t mention it when we first spoke, but, not too long ago, in an exchange with local historian Deborah Meadows, she mentioned a series of interviews conducted in 1913. “In 1913,” she said, “there were interviews of Ypsilanti citizens whose parents and grandparents were involved in local Underground Railroad activity.” According to her, the woman who conducted them, Mary Goddard, also interviewed two elderly women in town who had been former slaves.

MATT: Yes… If I’m not mistaken, the George McCoy story that we discussed last time, about slaves being transported to Detroit inside a secret compartment in his wagon, came from that series of interviews.

MARK: To your knowledge, are Goddard’s interviews public? I’d particularly like to read the interviews with the two former slaves noted by Meadows.

MATT: They are not published or available as far as I know, but the findings are presented in a paper (“The Underground Railroad”) to the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1913 and held at the Ypsi Historical Society Archives in the UGRR file. In addition to this, there is also the research which was collected by local historians A.P. Marshall, Carol Mull and others.

I’ve done a bunch of research on documents, but I’m not sure if we will uncover any more primary source accounts from Ypsi. There may be some diaries or letters in a drawer somewhere out there that might surface, but we are limited in terms of direct stories of the UGRR. But who knows what might show up.

We do have many local buildings associated with the UGRR, though, that go entirely unrecognized. For example, for all the claims of existing Ypsilanti homes having been stations on the Underground Railroad, and I have heard dozens, I have yet to see a single one verified by primary sources. We do, however, know for certain of a dozen or so existing homes where passengers on the Railroad lived, raised families, and built this community. [Right: 315 South Adams, the former home of Richard Hamilton]

We do have many local buildings associated with the UGRR, though, that go entirely unrecognized. For example, for all the claims of existing Ypsilanti homes having been stations on the Underground Railroad, and I have heard dozens, I have yet to see a single one verified by primary sources. We do, however, know for certain of a dozen or so existing homes where passengers on the Railroad lived, raised families, and built this community. [Right: 315 South Adams, the former home of Richard Hamilton]

We’re also lucky that folks in Canada, like historian Bryan Prince, steward so much of this information. I have learned and understood more about this subject by traveling to Ontario and visiting the cemeteries, museums, archives, and churches than by researching what is available here. That makes sense, of course, as Canada was the terminus of the UGRR, and those with these stories ended up there. I hope to make many more trips.

The community museum in Chatham, Ontario, and and the one in Buxton, are marvelous examples of local history, and have rich archives which detail many Ypsilanti families. Everyone with an interest should make the short journey to visit these museums or gather for the annual Homecoming Celebrations on Labor Day there. We are hoping for a bus tour for next year’s celebration in Buxton.The cemetery in Buxton contains the graves of so many ancestors of Ypsilantians, many of whom escaped to freedom. It’s an incredibly moving and picturesque place. Ypsilanti ought to seriously think about partnering with those towns in telling this story. [Below: The North Buxton Community Church Cemetery]

MARK: I know you said that you’ve never seen Goddard’s original interviews, but what do we know about these two former slaves from the accounts at the Ypsi Historical Society?

MATT: They were of two elderly women, Caroline Hill and Martha Washington, who came to Ypsilanti from Canada after the Civil War. Martha was born into bondage in Virginia, and came to Ypsilanti from Colchester right after the Civil War. Caroline fled with her lover all the way from Alabama, eventually making it to Chatham, Ontario. After he first husband died, she remarried and moved to Ypsilanti.

Carol Mull’s Underground Railroad in Michigan tells some of their story. One of the projects on my list is to go into some deep history about the places these women came from and what happened to those plantations after they fled.

Carol has done a huge amount of research looking into sources for her book and anyone interested in the subject should read it. The book is essential and contains much information on the Ann Arbor/Ypsilanti abolitionist movement, and many of the people related in this interview are covered at length in it. I hope the work that I have done looking into the roots and routes of the area’s black community is seen as supplementing Carol’s work.

MARK: Speaking of research, I’m curious as to what resources, if any, are available through organizations like the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati? You mentioned the archives in Canada, but I’m curious as to other sources where we might find archived documents that reference of activities that took place in Ypsilanti, or those people who lived here.

MATT: I’m originally from Cincinnati and that area has a rich tradition of abolitionism (and racism). The Freedom Center there is definitely worth a visit, but isn’t really a archival research institution.

The Charles H. Wright Museum in Detroit has done some great programs on area black history, including the Underground Railroad, and has archives that the public can access.

And Ohio has the Seibert collection, made in the 1890s, on abolitionism. It contains references to Ypsilanti, as do the letters of people like William Lloyd Garrison and Henry Bibb, both of whom visited Ypsi on speaking tours against slavery. The Provincial Freeman and the Voice of the Fugitive, were black-published newspapers of the time in Canada, and they both reference Ypsi frequently, as does Garrison’s The Liberator, which covered the 1863 Michigan statewide “colored men’s” convention held here.

MARK: You were quite clear on the fact, during our first interview, that the Underground Railroad was first and foremost a black enterprise, but there were white Ypsilantians, like Helen McAndrew and Leonard Chase, who did assist in the movement, correct? [Right: Helen McAndrew]

MARK: You were quite clear on the fact, during our first interview, that the Underground Railroad was first and foremost a black enterprise, but there were white Ypsilantians, like Helen McAndrew and Leonard Chase, who did assist in the movement, correct? [Right: Helen McAndrew]

MATT: Yes, of course. Those are some names associated with the anti-slavery movement here. There are many other names, like the poor white Prescott family who lived near to where the Peninsula Paper Mill was. They’re known to have brought black children into their home to teach. The Norris family has a split relationship; Justus Norris was a leading local Liberty Party member and Lyman Norris, his nephew, I believe, was counsel for Dred Scott’s owner, Dr. John Emerson.

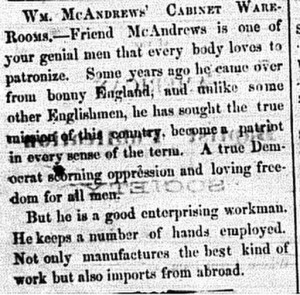

The Helen and William McAndrew family were all-around social reformers. Emigrating from Scotland in 1849, the McAndrews settled in Ypsilanti after teaching blacks to read forced them to leave Maryland. Here, they built an octagon house on South Huron which also served as a medical clinic. Helen would go on to get her medical degree specializing in children and women, and treat the impoverished and African Americans, the only Ypsilanti doctor for years to do so. [Right: The McAndrew’s house at 105 South Huron]

The Helen and William McAndrew family were all-around social reformers. Emigrating from Scotland in 1849, the McAndrews settled in Ypsilanti after teaching blacks to read forced them to leave Maryland. Here, they built an octagon house on South Huron which also served as a medical clinic. Helen would go on to get her medical degree specializing in children and women, and treat the impoverished and African Americans, the only Ypsilanti doctor for years to do so. [Right: The McAndrew’s house at 105 South Huron]

William McAndrew is remembered by his son as “help[ing] hide the runaway Negroes in barns and [driving] them in wagons at night, covered with loose hay, to the outskirts of Trenton, where rowboats ferried them to Canada.” After the war, the McAndrews would remain committed to women’s suffrage, childrens and health issues, temperance and religious and racial tolerance. Dr. Helen McAndrew is a member of the Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame and is buried near the integrated Union soldier’s ground in Highland Cemetery. [Right: Ypsilanti Commercial ad, 1864]

William McAndrew is remembered by his son as “help[ing] hide the runaway Negroes in barns and [driving] them in wagons at night, covered with loose hay, to the outskirts of Trenton, where rowboats ferried them to Canada.” After the war, the McAndrews would remain committed to women’s suffrage, childrens and health issues, temperance and religious and racial tolerance. Dr. Helen McAndrew is a member of the Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame and is buried near the integrated Union soldier’s ground in Highland Cemetery. [Right: Ypsilanti Commercial ad, 1864]

Leonard Chase was a radical abolitionist and had a property near the Rail Station in Depot Town. There are many unsubstantiated rumors about tunnels and UGRR activity in the area, but it is certain that Chase operated near the railroad. He was involved in both anti-slavery and UGRR work in Ypsilanti from his arrival in 1841 from New York until moving to Wayne County in the 1850s. Goddall relates that children, including Maria Morton, were occasionally instructed to bring food for freedom-seekers harboring with the Chase family. He was a blacksmith and lived openly in an interracial household, in 1850. [Below: 1860 Depot Town map. The Chase property would have been behind the Thompson Block – center, far right in the image.]

In 1850, Chase and his wife, Sarah, with their two daughters, shared their home with a five year old black child, Nathan, a family from the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii – and who are recorded as black) and a single thirty year old black farmer from Virginia, Adam Delon. These were not employees of the Chases, as the McCoys were on the Starkweather Farm, but boarders sharing their home. Surely, the most multicultural home in Ypsilanti at that time, and probably for many years after. One can just imagine the rude speculation the household received from locals.

Much of the culture and personalities of the abolitionist movement would have been recognizable to today’s social activists; from the endless meetings and debates associated with political struggles to the boycotting of goods and the organizing of forums and raising money. Every time I read about the personalities of abolitionists, they seem familiar to me from my own experiences. For example, a wedding of an abolitionist couple might make sure to include a commitment to anti-slavery in their vows as well as ensuring the whole ceremony, from the sugar in the wedding cake to the fibers of the bride’s dress, were not harvested or made by enslaved people. They might also, in lieu of gifts, ask that you give to the Michigan Anti-Slavery Society or a particular campaign to win freedom for someone in bondage. And, it goes without saying, they would only be married in an anti-slavery church by an abolitionist minister.

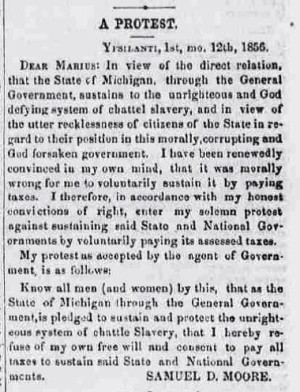

The Liberty Party was active in this area in the 1840s and the Signal of Liberty was published in Ann Arbor by the Beckley’s, so we have quite a bit of information about who the most active white abolitionists in the area were. Samuel Moore and a family of radical free-thinkers by the name of DeGarmos, were among the most active. The role of women in the movement changed as well, becoming more (publicly) prominent in later years. In the 1843 Governor’s elections, the Liberty Party’s James Birney got just 6% (28 votes) in Ypsilanti and 13% (82 votes) in Ann arbor; somewhat better than what the Green Party would get today. (For some reason, Salem Township, just north of us, led the county with 26%.) [Right: Anti-Slavery Bugle, 1856]

The Liberty Party was active in this area in the 1840s and the Signal of Liberty was published in Ann Arbor by the Beckley’s, so we have quite a bit of information about who the most active white abolitionists in the area were. Samuel Moore and a family of radical free-thinkers by the name of DeGarmos, were among the most active. The role of women in the movement changed as well, becoming more (publicly) prominent in later years. In the 1843 Governor’s elections, the Liberty Party’s James Birney got just 6% (28 votes) in Ypsilanti and 13% (82 votes) in Ann arbor; somewhat better than what the Green Party would get today. (For some reason, Salem Township, just north of us, led the county with 26%.) [Right: Anti-Slavery Bugle, 1856]

Our location next to Detroit, though, and the prospect of freedom in Canada, is as responsible for the arrival of fugitives in this area as the work of local abolitionists. If no abolitionists were here, fugitives from slavery would still have to travel through Michigan from almost any place west of the Appalachians to get to Canada.

MARK: Is there any evidence as to how accepted the activities of abolitionists were in Ypsilanti prior to the Civil War?

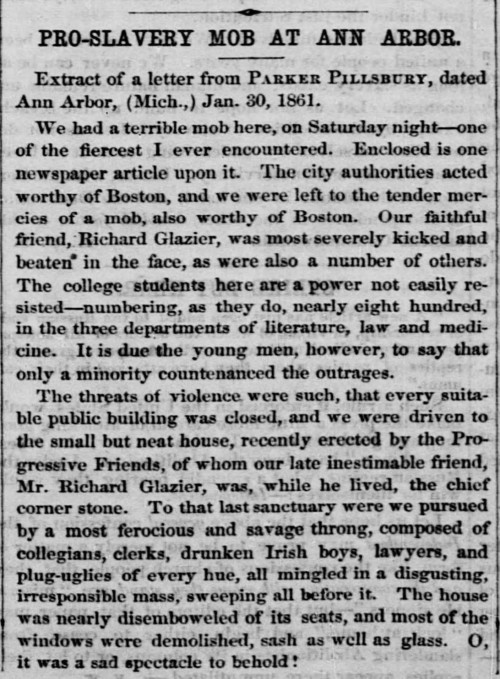

MATT: A number of Ypsi’s wealthiest families at the time would have been sympathetic to anti-slavery politics and I am sure that made the situation here more tolerant for abolitionism than many other places in Michigan and significantly more tolerant than some other regions of the North. The local Democratic press at the time was nothing but vitriol against the abolitionist movement and the Liberty Party, and there certainly would have been hostility toward abolitionist gatherings and public sentiments. Ann Arbor saw a number of attacks on abolitionist meetings over the years. [Below: The Liberator, February 8, 1861]

White abolitionists would have been a small, despised minority, even in Ypsilanti. (We like to think that everyone was an abolitionist – they weren’t.) They would have been on the very margins of society. They proposed upending the very way society worked. And, because of that, they were about as popular with the general (white) public as members of the Communist Party were at the height of McCarthyism. It didn’t get you invited to a lot of dinner parties. On the other hand, leaders in the movement would go on to play leading roles in local and state government during, and immediately after, the Civil War.

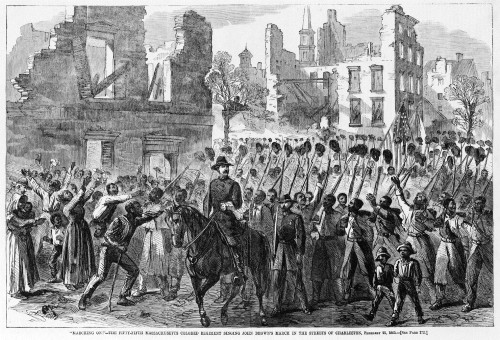

The war really did transform politics. White abolitionist officers would come to lead blacks, many of whom had just recently escaped to Union lines, in uniform, and under arms against slave-owning officers of the Confederacy. Just few years before, the Supreme Court said they “had no rights any white man was bound to respect,” and John Brown was hung as a traitor. By 1865, though, black troops, including many Ypsilantians, were marching through the street of Charleston, South Carolina, secession’s citadel, singing “John Brown’s Body” over the rubble of a defeated Confederacy. They included the middle-aged escaped slave “Father Cazy” who insisted, despite his years, on joining on as a nurse to the all-black 55th Massachusetts Infantry. Profound. [Below: The Fifty-Fifth Massachusetts Colored Regiment marches through the streets of Charleston, February 21, 1865]

MARK: You mentioned the Signal of Liberty earlier. Were there other local papers of note that pushed the anti-slavery agenda?

MATT: For a few years in that period, during the Civil War and Reconstruction, the Ypsilanti Commercial would have been a radical Republican paper and closely associated with anti-slavery, women’s suffrage, education reform, temperance and religious questions long debated within the abolitionist movement. [Below: Masthead of the Ypsilanti Commercial, April 14, 1865]

In time, the Commercial would go on to to become as anti-black as the white supremacist Democratic papers of the day, and Ypsilanti, despite its abolitionist past, would become more, not less, segregated than other Michigan cities. But that’s another story, though certainly connected.

MARK: You’re referring, at least in part, to the rise of the Klan in Ypsi, right?

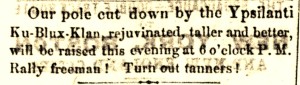

MATT: Well, the rise of reaction of which the Klan was a part. Immediately after the Civil War, the Klan was active in Ypsilanti, attacking the polling places of “black Republicans.” I expected to find the Klan in Ypsi in the 1920s, but I was a little shocked to find reports of Klan activity here the very year it was born. I did not expect that the Klan, a Southern phenomenon when it was first formed, to find an echo here then. The later Klan, of the post-World War One era, was largely directed at migrants, both black and Catholic, and Slavic immigrants from Europe coming into the largely white, Protestant, north. For the original Klan to find support here says a lot. [Right: The Ypsilanti Commercial, September 12, 1868]

MATT: Well, the rise of reaction of which the Klan was a part. Immediately after the Civil War, the Klan was active in Ypsilanti, attacking the polling places of “black Republicans.” I expected to find the Klan in Ypsi in the 1920s, but I was a little shocked to find reports of Klan activity here the very year it was born. I did not expect that the Klan, a Southern phenomenon when it was first formed, to find an echo here then. The later Klan, of the post-World War One era, was largely directed at migrants, both black and Catholic, and Slavic immigrants from Europe coming into the largely white, Protestant, north. For the original Klan to find support here says a lot. [Right: The Ypsilanti Commercial, September 12, 1868]

Ypsilanti was largely a conservative town with pockets of progressives around the black community and the Normal College, but it wasn’t at all universal. Lincoln won the election here in 1860, but lost in 1864 in what was seen as a referendum on a war for abolition. Jim Crow, though not codified in law, would also become a reality in Ypsilanti. By the 1890s, Ypsilanti had become a very segregated town. This was Michigan’s largest black city of the era, by percentage, so the racial politics of the day were bound to vigorously be played out here.

MARK: I imagine it’s hard to know, but do you have a sense as to how many runaway slaves may have found their way to freedom through Ypsilanti?

MATT: The total number is probably a little larger than I would have first imagined. In the 1850s, when the UGRR really gets going, Ypsilanti’s (official) black population more than tripled, from under 100 in 1850 to over 300 in 1860s and hundreds more by the 1870 Census. Reports indicate that upwards of 30,000 had made it to Canada by the Civil War, though certainly not all through Michigan. Given those numbers, I would be comfortable in guessing that hundreds more came through Ypsilanti who didn’t stay; others would return from Canada after the Civil War on the basis of connections made in the period of the Underground Railroad. Many hundreds of passengers on the Railroad would have seen Ypsilanti and it is possible that the total number was as high as a couple of thousand over the decades, but we will never know for sure. What is sure is that the community they built, and that their descendants continue, thrives to this day.

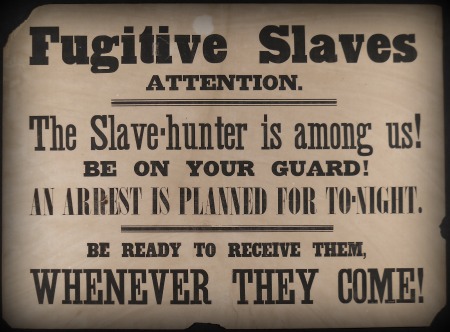

[The fugitive slave poster at to top of the page is from 1850s New England, and comes courtesy of Dartmouth’s Rauner Library.]

15 Comments

I’m hesitant to look into my family’s southern past as I’m afraid of what I might find there.

Thank you for your work, Matt. This is fascinating.

Kim,

Thanks for your kind words. Never be afraid of the past; the only guilt is in not knowing! Matt

Matt, can you elaborate on rumors concerning the existence of tunnels in Depot Town? I’ve never heard mention of such rumors.

Mr X.

There are pre-(Civil)war sewage and water tunnels that run under Depot Town to the river that became a source of rumor about the UGRR in the early 20th Century. I think folks take the “Underground” part of the Underground Railroad too literally.

This is a wonderful and informative article. Thank you so much for the interview with Matt. We are so fortunate to have him doing and sharing his research!

How much money would it cost to create an HP Jacobs plaque in town? I bet we could raise it on Kickstarter pretty quickly.

Im thankful for the information presented here in this post and curious about William Pollard who’s name is in the A.M.E church in Ann Arbor. He lived at 422 South Adms Street.

Harold,

Thanks for reading. Please contact me at southadams1900@gmail.com. I have quite a bit of information on William Pollard, who was formerly enslaved in Virginia and a member of the 102nd United States Colored Troops during the Civil War. . I’d be happy to share what I have with you.

Matt, I’m wondering if you could say a few words about your experience learning all of this. What surprises you about what you’ve researched? How has your understanding of the Ypsilanti area changed since you first started this research? Great interview!

Lisa- thanks for the questions. Lot’s of surprises, and they keep coming. I think the biggest takeaway from my research is just how central the African-American story is to Ypsi. It’s not possible to understand the town’s development or even physical layout without that perspective; it’s what makes Ypsilanti so different from Saline or Northville, towns in the area that have a lot in common with Ypsi- started at the same time and by the same types of people (more or less) – but are now very different from Ypsi. Ypsi was and is, in many ways, an African-American city going way back; it’s what makes Ypsi unique.

Great! Thanks.

Mark and Matt: Thank you for this information. The best l’ve ever read about Ypsilanti’s African-American and Native American histories. And, happy to have found your blog as another source for local news.

My name is Annette Wright. I am one of Adam and Sarah Crosswhite’s great x3 grand-daughters. I am also the great-great grand-daughter of Sarah Crosby. My birth name is Annette Marie Crosby. I was born in Toledo, OH. My father’s name is Frank A. Crosby, Jr., his father’s name is Frank A. Crosby, Sr., his father’s name is George Crosby born to Sarah and Lafayette Crosby.

I am desperately seeking information about my grandparents. I understand that my great-great grandparents, Sarah and Lafayette Crosby resided in Ypsilanti for many years.

Do you have any photographs of them or their son, George? I have census records and birth/death records. I have visited both Kentucky and Marshall, Michigan.

I would appreciate any information that you can share.

Thank you kindly.

Annette,

Please email me at southadams1900@gmail.com. I do have some information. So glad you found this!

Matt

The Debaptise, The Crosby’s, and the Hamilton’s are all my family. Richard Hamilton was my grandfather and I grew up spending the summers in that house on South Adams.

3 Trackbacks

[…] UPDATE: Part II of this interview is now available. […]

[…] In this first installment, he both celebrates the life of local janitor turned university president HP Jacobs and tarnishes the legacy of Rosie The Riveter, who he says fought to keep black workers out of the […]

[…] In this first installment, he both celebrates the life of local janitor turned university president HP Jacobs and tarnishes the legacy of Rosie The Riveter, who he says fought to keep black workers out of the […]