My old friend and former bandmate, Pete Larson, moved to Kenya a few years back to oversee a number of public health related research projects. And, while there, he fell in love with the country’s culture and music. Now, like a good academic, he’s doing his best to document and preserve what he can, starting with the work of Oduor Nyagweno, one of Nairobi’s last Nyatiti players. Following, for those of you who would like to know what exactly a Nyatiti is, is the transcript of my most recent transcontinental discussion with Pete. He, in case you’re interested, was eating goat brain soup, and I was sipping on a kale-beet-carrot smoothie.

MARK: Hey, Pete.

PETE: Hey, Mark. How are you doing?

MARK: I’m good. Where are you?

PETE: I’m in Nairobi?

MARK: How are things in Nairobi?

PETE: Nairobi is like a summer day, every day.

MARK: And that’s a good thing?

PETE: Yeah, I think so.

MARK: Awesome… So I hear you have a new record coming out?

PETE: I do. It’s on Dagoretti Records, which is a new record label we just recently started here in Kenya.

MARK: So what’s the new record?

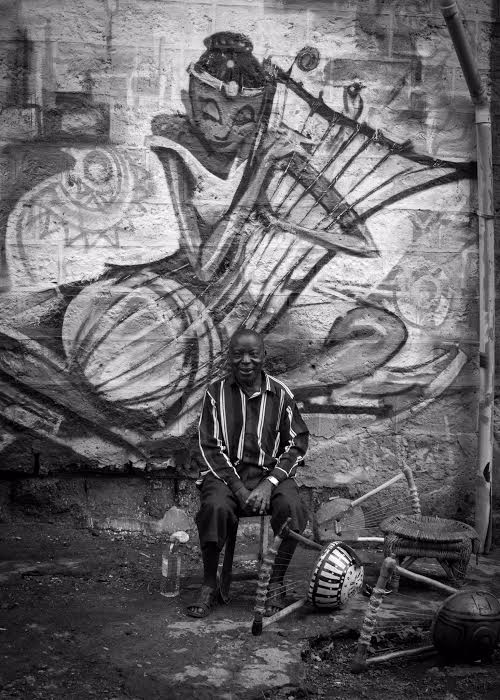

PETE: It’s by “Oduor Nyagweno and the Nyatiti Attack,” and it’s called “Teach Me, Teach Me.” Oduor Nyagweno, who I find myself referring to simply as “the old man,” is the guy I’m learning the Nyatiti from… My friend Daniel Onyango and I both take lessons from him on this instrument called a Nyatiti… Anyway, this recording that we’re releasing has six songs.

MARK: OK, so the record isn’t out yet, but you’re releasing six songs now, online or something, in advance of pressing the record?

PETE: Yeah, these six songs all came from the same session back in January. And we wanted to get them out now, while we’re working on the full length album… We’re trying to raise money right now to put a full length record out on vinyl, and we thought that, by making some of these tracks available, people might be inclined to contribute a few dollars…. It’s going to be a really great record. I’m really proud of it. We’ve put in a lot of work so far, but it deserves it… It deserves a real release.

MARK: Are the tracks we’re talking about traditional songs that people might know in Nairobi? Or are these things that the old man has written himself?

PETE: Well, these first six songs that we’ve just released, are mostly folk tunes. So, yeah, people would know them here in Kenya. So, for example, the first track is called “Dodo,” and it was popular way back in the 1970s, when it aired on television as part of an ad campaign directed at drinkers. The message was essentially, ‘Don’t get caught drinking.’ The song didn’t tell people not to drink, it just told them to not to get caught drinking. And kids would sing this song in the hood, like, you know, they would just sing it because it was all over the radio and all over the TV. And there are also a couple of other tunes that are folk tunes from various traditions throughout Kenya. So it’s tunes that Kenyans would know, yeah.

MARK: So how did you come to know this guy?

PETE: Well, I started playing the Nyatiti about a year ago. It’s kind of a lyre-like instrument. There’s all different versions of it throughout East Africa, but they’re all related, having come down from Greece, through Egypt, and down the Nile to the Lake Victoria region.

And, a couple of years ago, I saw Daniel Onyango, who’s now my friend, playing the Nyatiti live, and I went up to him afterward and asked him if he could give me lessons, and he introduced me to the old man. The old man is really just one of two elder Nyatiti players out there. He’s about 70. He’s doing pretty well, but he’s old. And I would go and sit with him once a week, twice a week, several times a week. Sometimes I’d go to his house, if his gout was flaring up. And sometime he’d come up to the Kenya National Theater and teach me songs. And it’s been a really great time. It sort of makes being in Kenya worth it.

MARK: So, how much money do you need to raise for the vinyl?

PETE: It’s not cheap, you know. We need about $3,000 or $4,000 to make it work. And I’m hoping we can at raise at least get half of that… It’s really incredible stuff. It’s great to hear him sing. He’s a great singer, a great player. And, culturally, it’s incredibly significant to have this out, because, when he goes, that’s it. It’s gone. You know, there’s no young people doing this kind of music in the way he does. And this type of music, this type of poetry, needs to be preserved, because it’s not being passed down anymore from old people to young people.

MARK: And what language, or dialect, are the songs sung in?

PETE: The finished record will have eight songs, all played by Nyagweno, and they’re all in Luo. We’ve gotten all the songs translated, though, so there will be a lyric sheet with translations, as well as explanations about the tunes that I wrote with my friend Rapasa here in Nairobi, who is also a Nyatiti player.

MARK: Are there any academics studying this stuff?

PETE: No. There’s like one guy at Kenyatta University who wrote his dissertation on the Nyatiti several years ago, but, no, no one is doing any work on this at all. I mean, in the world there’s only 20 people that play this instrument, and that includes me.

MARK: Oh, I’m sure it will catch on now that you’re involved.

PETE: Well, I doubt it. Nothing I do seems to catch on, but that’s okay.

MARK: So who’s the other old guy that plays? I’m just kind of curious as to whether there are any politics involved, for instance, if they’re from different groups… I think you and I talked about this before, about different ethnic factions. You know, is Nyatiti just played by one ethnic group, or there are multiple ethnic groups that play? And is this other old man perhaps from a different faction?

PETE: Well, yeah, there was some of that. You know, it used to be an instrument from a specific region of Kenya… the songs were sung in Luo traditionally. I mean, it’s not… I don’t want to say it’s “a Luo instrument,” because the Luo people are so widespread, and it’s really just from this one area. But, you know, that has changed a lot. And that’s one of the things we’re trying to address in the movie that we’re making along with the record, which I’ll get to in a minute. Here’s this instrument that started with these Luo guys, and it’s now being played by people like Dan Onyango, who are like Nairobi University educated, you know, Kikuyu-speaking, Swahili-speaking, English-speaking, young people. They don’t sing Luo like the old guys did. And a lot of these guys that are playing now don’t even speak Luo. I can think of two people in Nairobi that play the Nyatiti and speak Luo, the rest are like from other tribes, speaking other languages.

So it’s sort of like we’re preserving this old type of poetry, singing style, and not just the instrument. And, more importantly, at the same time, we’re seeing young people move on from this tribal nonsense, take things from one another’s tribes within their country, and do new things with them. And I think that’s super.

MARK: What kinds of things do Nyatiti players generally sing about? What, traditionally speaking, is the poetry of Nyatiti players about?

PETE: It’s a lot of things that are common to African music, like praise songs, or songs about how great the singer is, but the themes usually contain really vulgar elements. We have one track on the full length record that’s a tribute to Barack Obama that starts out with some story about a guy in the village couldn’t get an erection, so his wife went and complained to her mother that there wasn’t any action going on at home, the implication being that she’s now free game. Inexplicably, he moves on to talk about how Obama gives people iron roofs, and beats Hillary Clinton in the election, and what a great man he is. (It’s worth mentioning that Obama and Nyagweno are related through the same clan.) It doesn’t make a whole lot of sense to us, but that’s the style these guys sing in.

Another one lists all the women that the subject of the song has slept with, which is nearly all locals guys’ wives and daughters. Of course he names them all, because everyone knows all the dirty secrets of the village. And there’s all these double meanings and innuendo, like one song I worked on with the old man is ostensibly about playing the Nyatiti morning till night, but the word choice implies that the singer is having sex with all the women in the village constantly. “I’m playing this girl all day long,” where the girl is either the instrument or any number of real girls.

It’s usually hard to get parents to allow their kids to learn the Nyatiti because these songs are intended to be sung in drinking places, where people like to talk about those kinds of things. Above that, people out there just simply like crude stories about sex, just like people everywhere else. It’s a lot like hip hop in the States, but I still always find the divide between English and vernacular culture here to be completely fascinating. English is boring and stodgy while the vernacular languages are colorful, complex and fun.

MARK: OK, so the old man is Luo, right?

PETE: Yeah, the old man is Luo. Both of the old men are Luos. And they’re from opposite sides of a river out in Siaya, and there’s somewhat of a rivalry between the two. They don’t bash each other, but there is a rivalry there.

MARK: Like a Biggie, Tupac kind of thing?

PETE: You know, it really was. A long time ago, that’s the way it was. You know, Nyatiti used to be like… they had these competitions, kind of like rap battles, like you’d see in Eight Mile, where they would sit around a circle and they’d play, starting at seven at night, and go on to seven in the morning. And people would be drinking and having a good time, and these guys would take turns talking about how great they were and how much better they were than all the other guys. These were apparently serious rivalries. And the stakes were high, like, the better you play, the more likely you were to win the prize, which was something like a bicycle, or a cow, or something that was really expensive at the time.

So these guys were like, they were out to get each other. And I’m not going to repeat what what I’ve heard, but there are really salacious stories about them putting curses on one another to screw up their playing, among other things. There was all kinds of crazy stuff. But, for the most part, the rivalries were quite friendly. They were borrowing off one another to improve their technique and sound, just like hip hop guys do, which is the closest analogy.

MARK: So I’ve seen clips of the videos that you shot and most of them have been about the music. Are you also getting into the history of it? I mean, are you interviewing people about this past on camera for the video?

PETE: Yes. So we’re working on a documentary right now called “Nyatiti Stories.” And we’re interviewing, basically, whoever we can, who plays the Nyatiti, or is associated with it in some way. And we’ve interviewed both the old men and gotten them to sit down and tell us some stories. And part of that has been going into the culture around the instrument and the poetry associated with it, and it’s been incredibly fascinating. It’s not just about learning to play eight-string instruments, it’s also about the deeper traditions associated with it, which are not really that much different from what we would see in hip hop for example. I mean, it’s really not that much different in the end.

MARK: Is there like a Nyatiti festival somewhere where all these 20 people come together? Do people know of each other, these 20 people that play?

PETE: Oh, yeah. All these guys, ladies, they all know each other. But, no, they never get together. That’s the way it used to be, it’s like all these Nyatiti guys would get together and they’d play at these festivals and compete, but that doesn’t happen anymore. Nairobi, the music scene in Nairobi is like, tends to operate in a way where they don’t go out of their way to actively obstruct one another, but, at the same time, they also don’t come together very much. I don’t know whether that’s because it’s Nairobi, or it’s because it’s 2017, or it’s because, whatever, but, no, they don’t do that anymore. In many ways, it’s analogous to how the entire country works. It’s difficult to get people to want to pull together for a common goal.

MARK: And the Nyatiti, I assume, isn’t seen in bars because bar owners don’t think there’s a market for it….

PETE: Yeah, that’s it. I mean, this is going to sound terrible, but one thing that really is different about musicians in the states and here is that a lot of musicians in the states don’t necessarily need to do it for a living. Here, there’s money involved. They are eating off this, and they’re not really motivated to work with each other unless there is money involved. That’s just the way it is. Life is hard here. It’s not easy. It’s one of the most expensive cities in the world. And a lot of the people that play, never went to school or anything, so this is what they do. They don’t really have time to just play around, which is good and bad, I guess. I don’t know.

MARK: Ao what’s next for you? How much more work do you have to do on the documentary?

PETE: We pretty much finished shooting. We’ve shot about 50 hours worth of footage at this point. We’ve filmed shows, and interviews, and a number of other things. We’ve followed people around. So, right now, we’re just looking at editing and seeing where this is going to go. And, hopefully, we’re going to take it somewhere and people will see it. I’m writing a book too. It’s a companion piece that will go along with the movie. It’s not an academic book. It’s more a compilation of all the stuff we couldn’t fit into the documentary, plus the interviews. And then there will also be a CD compilation release that will come out of it too, of all these different people playing.

MARK: And have you guys been writing original music too? Like, you mentioned that the first six songs on this release, the online release, are all kind of folk songs. Are there other pieces, though, that you guys have written together with the old man?

PETE: You know, the old man has always written songs. He’s got hundreds of songs. It’s ridiculous how much he does. He writes songs, he doesn’t remember them. Sometimes he’s like, ‘I have this song,’ and he plays it for me, and the next week he doesn’t remember. Like, yeah, he is always writing tunes. And I used to play along with him, he just would play the riff and we would play along and I’d learn from that. It’s a great experience. But I’m working on music with my own band, Ndio Sasa, playing Nyatiti in that band, and also playing with Dave Sharp, who came out a few weeks ago and played with us here in Nairobi. It was a good time. So yeah, I mean, there’s a reason for all of this music to come out…

MARK: I didn’t know Dave went out there. Did you guys write together, or did he just come out to record you guys?

PETE: No, he came out with some jams. I was there, my friend Colin Crowley, our percussionists for Ndio Sasa, Kaboge Chagala and Tomo Tsukahara along with Boaz Jagingo from the band Kenge Kenge Sound System who have played in more than 100 countries worldwide. We had probably two of the greatest musicians, greatest young musicians in Kenya right now. Boaz plays this violin kind of instrument and sang. It was fantastic, it was a great time. Yeah.

MARK: Should we expect to see recordings of this stuff coming out?

PETE: Dave’s going to put that one out, you know. I’m hoping I can get a couple of tunes from the sessions for an EP. But, Dagoretti Records, we’ve got several things in the works. We’ve got the Nyagweno full length, I’m talking to another Nyatiti player here in Nairobi named Rapasa and I’m trying to get a full length release on him. Maybe an Obokano record, which is like a big version of the Nyatiti. I’ve got another record by a band in Japan called Sick Trees and there are two records by my band Ndio Sasa. So there’s lots of stuff coming out.

MARK: And after you’ve recorded all the Nyatiti stuff, and maybe branched out to document the Obokano, are there other traditional instruments that you might want to look at?

PETE: I play the Shamisen, which is a three-stringed instrument from Japan. I’ve also started picking up the Orutu, which is like a violin kind of instrument. It’s like a one-string kind of mountain violin thing.

MARK: Yeah, I’ve seen you playing one on Facebook.

PETE: Yeah, it’s cool. It’s like, you know, one string, you only get five notes out of it, but the sounds are cool. And I still play guitar. So I’m doing all kinds of stuff… But the Nyatiti is everything right now. I’m all about the Nyatiti.

MARK: I’m happy for you, Pete… Is there anything else you want people to know about the project?

PETE: So the record is available on Bandcamp right now. And it’s a free download, but we want to encourage people to pay some money for it if they can, whatever they want to pay, because we’re trying to raise capital to do a final release, and to get all of this other stuff going, and do more if we can. It’s on Bandcamp. So please go there.

We also have our YouTube page for Dagoretti Records which has numerous videos of Nyatiti music and Shamisen music, and music from all over Kenya. So please go there and check that out too.

MARK: Do you have a distribution network there for the records once they come out? Can you sell them in Kenya? Do people have record players there?

PETE: No. I mean, we may be able to sell a couple in Kenya, but, for the most part, it’ll be CDs in Kenya. It’s nearly impossible to sell records in Kenya, though. I mean, people don’t have a lot of money, and that’s why we made all of our releases free downloads with the option to pay for those who can. We wanted to make this accessible to people here if they wanted it, so they can get it for free. I mean, it doesn’t make sense to try and sell this kind of thing in Kenya.

MARK: Yeah, I understand… I’m just wondering if there are record stores in Kenya.

PETE: Oh, no, no, no. I mean, there is like one record store here in town. It’s really old school. They sell old Kool and the Gang 12”s and stuff like that, which is cool, but the vinyl, and even physical releases, are long gone here.

MARK: Cool. Well, it’s been nice talking to you.

PETE: Yeah, it’s great talking to you. Stay hungry.

MARK: One last thing… I thought you told me you’d never start a record company again. What happened?

PETE: It’s the only thing I know how to do… I went through a particularly bad spot in my life, and sort of instinctively defaulted back to something I know and can do. When shit goes bad, you really have to move where you feel comfortable. So, yeah, I said I’d never do it, but I did… and, truthfully, since there aren’t any expectations now, it’s much easier, and far more fun.

MARK: So, how is this different from the experience of starting Bulb Records?

PETE: In the past, I didn’t really know all that much about music. It’s better now that I have some clue about what music really is. It makes it much easier to tell people to listen to it… Interacting with this kind of music has vastly increased my knowledge and understanding of music in ways that I could never have imagined. When you look at things through a lens that you’ve never experienced before, you develop a better understanding for how things work (and how some things don’t). I’ve always been fascinated with what music can do to people, and coming as an outsider in this kind of music has given me a seriously new perspective on everything. So, yeah, it’s easier now that I’m giving this a lot more thought than I would have in the past, and, again, it’s just more fun.

[Above: Video of Oduor Nyagweno playing the Nyatiti.]

[To download “Teach Me, Teach Me” by Oduor Nyagweno and the Nyatiti Attack, just click here. And don’t forget to make a contribution if you’re able to do so.]

7 Comments

Very interesting.

When Larson talks about how “super” it is that people from different tribes are picking up this Luo instrument and innovating with it, I’m reminded of the comments I’ve seen on this site about how terrible it is that Frank at Ma Lou’s is frying chicken as a white man.

Good work, Pete and Mark! I look forward to the vinyl and the doc.

That was good.

Great interview. So much is now clear… stuff I was a bit confused about from watching bits and pieces on Facebook

I will play this on my radio show on WCBN! (Mondays from 3-6:30)!!

Hi!My name is James I appreciate the good work Larson is doing down there in the Hoods of my country Kenya. The instrument Nyatiti is an instrument well recognized far and beyond Kenya currently being played in Japan , US, Italy , United Kingdom and many other counties of the world , In the previous years at the Kenya National Theatre I saw scholars who came and were taught by Another Old Man called Nyamungu a core rival of Mzee Nyagweno an American Scholar called Adams between 2001 to 2003 we issued him with a certificate , he was playing it very nicely ; then Came a Japanese lady who also learnt it together with the luo native language her name was Anyango Nyar Siaya derived from the Luo community her music are on u-tube che really plays it nice I remember we had a plan of developing a Nyatiti Learning School during this time but there was no enough support for the idea , we were issuing certificates Japanese Lady called came to Kenya stayed in Luo village and learnt the instrument together with the Luo language heck out Japanes Nyatiti player Anyango Nyar Siaya, latter my Friend Helena from Italy also learnt it through mzee nyagweno , she went back to Italy with instrument and now playing it both in Italy and Mauritius where she is working, mid last year she came here in Kenya and did a documentary with mzee Nyagweno and at the moment I am assisting her in Translations , Nyatiti songs are always the same ans sung the same way from one nyatiti player to the other.The instrument Nyatiti has some spiritual connections to the Luo ancestors and was considered a curse…

2 Trackbacks

[…] I have a friend who perhaps suffers from a similar affliction. He went to Kenya and got himself hooked on an instrument called a nyatiti, and now it can’t seem to break free of its grasp. It’s a huge part of his life now. […]

[…] moved away from Michigan in ’93, I must have given a copy of this recently surfaced video to Pete Larson, founder of Bub Records, for the label’s archive. [This would have been around the same time […]