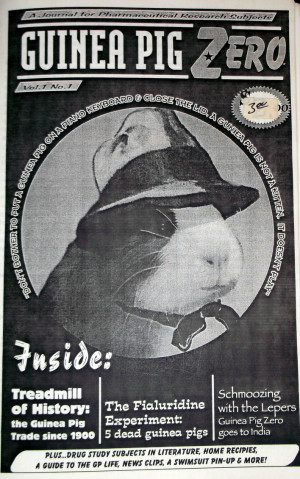

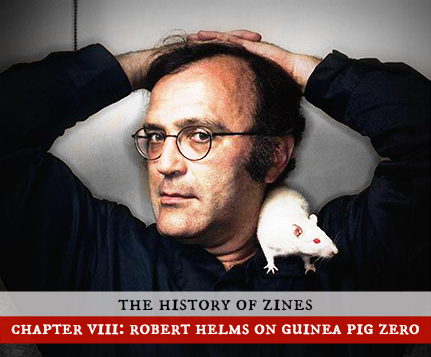

In an attempt to better document the American underground press, or at least the sharp, rusty sliver of it that infected me 20-some years ago, I’ve given myself the task of interviewing all of the zine folks that I respected back in the day, during the period which many of us still consider to be the golden era of self-publishing. Today’s interview is with Robert Helms, the man behind the journal for human research subjects, Guinea Pig Zero (GPZ).

MARK: My guess is that Guinea Pig Zero came about after you’d already been a human test subject for some time. Is that correct?

ROBERT: Yes. When I released the first issue, in May of ‘96, I’d already been doing medical studies on a regular basis for over a year. I’d also tried to do one back in 1990. I got cut from that one, though, because I fainted. I was all set up on PK Day – that’s when they dose you and the work begins – and, as soon as they put the catheter in my vein, I passed out. It happens to beginners. It’s called a vasovagal syncope. That’s when you pass out suddenly as your vein is punctured, or, sometimes, when you’re having a crap. It has something to do with the body experiencing fear, but I forget the details…

MARK: Do you recall when the idea for the zine came to you? Was there, perhaps, a specific experience that caused you to say to yourself, “I really need to start documenting this?”

ROBERT: I’d heard the idea floated by a guy who was already a guinea pig, and who knew about zines. (I’d known about zines then too, but only slightly.) This person who mentioned the idea of a guinea pig’s zine, coincidentally, was the same one who later went temporarily nuts from a drug study, which led to my article, “The SmithKline Beecham Debacle of 1996,” which in turn led to my being threatened with a lawsuit by the company. My friend (which he was at that time) never wrote a word about being a guinea pig, nor created any zine. His remarks on the idea got me thinking, though, and I ran with it.

MARK: Do you remember when it was that he first brought the idea up, and what the circumstances were? Were you and he having beers after a hard day of guinea pigging, or were you, maybe, laying next to one another, on gurneys, being dosed with something?

ROBERT: He and some other friends lived in a squat on Cedar Avenue in West Philly called the Brew Squat (the residents being caffeine addicts), and we shared an office on the ground floor. We were in the kitchen, shooting the breeze with one or two other folks, and he started talking about how guinea pigs had a shared workplace culture, and how a zine about that culture would be cool.

MARK: Where were you living at the time, and what, if you don’t mind my asking, did you need an office for?

MARK: Where were you living at the time, and what, if you don’t mind my asking, did you need an office for?

ROBERT: In the years when I published GPZ, I lived in a few different places in Cedar Park, the neighborhood where the Brew Squat was, and where all sorts of radical activity goes on. (It’s affectionately called the “anarchist ghetto” by some.) I never resided in a squat because I had a huge library in those days, and I’d never risk losing or ruining my books. Also, I always keep cats, and giving them a stable environment is part of the deal. Anyway, I moved a few times during that period. (Some of the time I was in France, living as a visitor.) As for the office space in the squat, we used it to agitate for IWW campaigns, and to publish a paper called the Free Voice. The letter “i” was dotted with a circled A. It was a local anarchist paper, and a good one, too. It’s preserved in a few archives now.

MARK: How was publishing the Free Voice similar or dissimilar from publishing the zine?

ROBERT: The Free Voice ran for about five months, and there was an editorial committee. So there were conflicting opinions about content, which I found annoying. We all felt that it was well worth the effort, though.

MARK: And, with the GPZ, I imagine that, while you had input and contributions from others, it was somewhat more autocratic in nature… Was that liberating as an editor, not having to run things by other people, and build consensus?

ROBERT: I had total control of the zine at all times. That was the best way. And I believe that’s why GPZ was so successful.

MARK: Speaking of the success, do you think that you could have leveraged it to have had a career as a writer?

ROBERT: When I started GPZ, I had no reason to believe that more than just a few people would read it. Other zine writers, even when they loved GPZ, would tell me, “Don’t quit the day job.” For me, it was a writing experiment.

Later, when I was all over the media, I probably could have found a way to write for the rest of my life. But I didn’t catch the ball. I wasn’t focused enough. And I only write well when I’m writing about something that makes me mad. The New York Times Magazine invited me to write an article on Prozac once. I said I didn’t know much about it, hoping that they’d give me something else, but the editor wanted only that. I promised the article, but I never wrote it. I just didn’t want to become the guy who, after a weekend of hurried research on a current mental health issue, could turn out a few clever sentences. Ever since, I’ve wondered if I should have done exactly that. I know I could have pulled it off, but it didn’t feel right. The upshot is, to write for a living, your situation has to be on a steady course, and mine just kept changing in all sorts of ways.

MARK: You mentioned that you were somewhat aware of zines when starting GPZ. How did you become aware of them?

ROBERT: I knew Jeff Kelly, the editor of Temp Slave, because we were both Wobblies. And I’d read a few job-zines… namely Dishwasher, which was the best one out there. When I started writing articles for that first issue of GPZ, in late 1995, though, the rest zine world was unknown to me.

MARK: When you say that you knew Jeff, as you were both Wobblies, do you you mean you knew of one another through IWW publications, internet usenet groups, and the like, or were you actually living in the same town at the same time, involved in some of the same IWW campaigns?

ROBERT: Jeff lived in Northeast Pennsylvania, in the Lehigh Valley. And, when we started the IWW branch in Philly, in 1991, Jeff and other Lehigh Valley Wobs came to the event, which was a little concert. He and I were involved in a few campaigns after that, and we stayed friends after he moved to Wisconsin. I haven’t seen him for quite a while now, though.

MARK: I need to track him down for an interview. The last I’d heard, he’d gotten married and was working in a cheese factory. I may be remembering this all wrong, but I seem to recall him telling me that it was his job to walk around these giant tanks of milk, sprinkling in enzymes, or some such thing…

ROBERT: He turned milk into cheese by doing what cheese people do in big cheese factories, and the pay was good. Europeans try the average piece of cheddar in the U.S. and they simply refuse to call it cheese. Same with Hershey’s Kisses. They’re not chocolate, to anyone who has eaten good chocolate. If you feed a Hershey’s Kiss to a Belgian, there might be punches thrown. As for Jeff, I heard some new development, not too long ago, but I forget what it was. He’s still in Wisconsin, though, I think.

MARK: One of the great things about zines is that, through them, we get to know people who, more often than not, don’t have a voice in the media. They’re not politicians, entrepreneurs and celebrities. They’re dishwashers, temp workers, and, in the case of Guinea Pig Zero, the people who we, as a society, test our cosmetics and erectile disfunction drugs on. They’re marginalized individuals who, for whatever reason, have decided to make their voices heard. There’s not always a political motivation at play, of course, but there often is. And I’m curious, in your case, to what degree you saw GPZ as an organizing tool. When you set out, were you consciously looking to raise awareness about the issues encountered by human test subjects? Or were you just looking to share interesting stories?

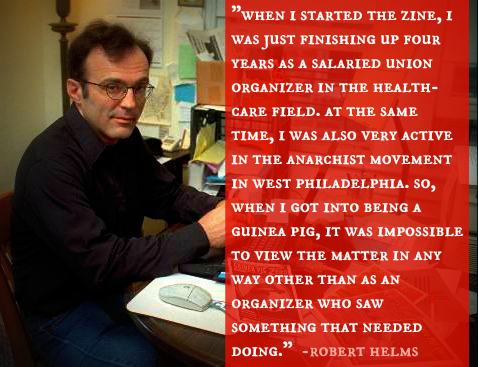

ROBERT: When I started the zine, I was just finishing up four years as a salaried union organizer in the healthcare field. At the same time, I was also very active in the anarchist movement in West Philadelphia. So, when I got into being a guinea pig, it was impossible to view the matter in any way other than as an organizer who saw something that needed doing. Also, I’ve always been a hog for history. And I knew that the history of medicine, just like all mainstream history, was leaving out the poor slobs. So, I caught the subject when I was on a roll. I was passionate about it, and people wanted to hear about things they weren’t used to hearing about.

MARK: Was Temp Slave the first zine you ever read?

ROBERT: I’m not sure what was the first, but it might have been. I must have perused whatever Wooden Shoe Books had in stock back in 1989, but I didn’t think about them enough to recall them now.

MARK: What did you think of Temp Slave?

ROBERT: It took what I’d refer to as a “rip ‘em a new asshole” approach when discussing abusive, stupid management in the workplace. This was, and still is, badly needed. The mainstream discussion takes care not to seem angry. It doesn’t use the harsh language that working people actually use when their boss is being a total asshole. Jeff never cut them any slack.

We need people like Jeff Kelly in the mix. Several times, I’ve followed news stories about workplace shootings, where a shooter walks around with the gun, shooting bosses and supervisors, but simply ignoring co-workers. He just walks past them, or leans to the side to get a clear shot at a boss, but not hit the rank and file person. Obviously, this should be called “bossicide,” but, when it happens, and every reporter in the country is examining the event, the talk goes straight to the shooter’s mental health, his troubled home life, and simply anything but this phenomenon that is bossicide. Once it happened in the sign shop of the Philadelphia Department of Streets. A guy I knew worked in a different part of the department, and he told me that every single dead person had been an obnoxious, belligerent, abusive, power-drunk scumbag. The shooter didn’t harm the workers who were sitting right beside them. Bossicide is the elephant in the room. And only a writer like Jeff, who doesn’t give a shit about the tender feelings of stupid assholes, will point out the obvious and clear pattern you see in cases like that.

MARK: Are you still a human test subject? If not, when did you stop, and why?

MARK: Are you still a human test subject? If not, when did you stop, and why?

ROBERT: No, I stopped doing studies almost entirely in 2003, when I turned 46, because 18 – 45 was the age range that the good studies in the U.S. were asking for. After that, the tests aren’t going to be often enough to plan one’s life around.

MARK: So, from 1995 to 2003, selling your services as a human test subject was your primary source of income?

ROBERT: It was a major part of my income – sometimes the primary source – during those years. I was also a house painter and a handyman/carpenter’s helper.

MARK: I wasn’t aware that these tests happened with enough regularity that one could expect to be able to keep jumping from one project to another. Would I be right to assume that this required you to travel quite a bit between different cities, and test units?

ROBERT: I traveled to some studies, but, living in Philadelphia, I was close to many units already. Philly has been a major center of medicine and the sciences since Colonial times. Of course, one has to lie, and say that the last study you did was at least four or five months ago.

Each research group has its own private list of volunteers. The way it works in the U.S. – unlike in, say, France – there’s no central database that keeps track of how many studies a person does, and how close they are together. So it’s simple, as long as you and the research staff stay in character. All experienced guinea pigs know, and every single doctor and nurse involved in such studies knows, 99% of the volunteers lie to qualify. If you’re too truthful, you get no work. And, If they get obsessive, and catch too many guys lying, they’ll wind up with too few reliable guinea pigs. For long or complicated studies, if the volunteer has never done studies before, there’s no way they’ll get it right. We pros would laugh like crazy at the mistakes new guys would make. The recruiters know all this, and it’s basic stuff for them. But they can’t say it on the record. If they did, they’d be stepping out of character.

The farthest I ever drove for a study was Kenosha, Wisconsin. I took that trip with Dishwasher editor Pete Jordan, who was living in Pittsburgh at the time. He entered a study, which he later wrote about for GPZ, and I was planning to do it with him. We both screened and qualified for the study in Kenosha. (It was at Abbott Labs, I think.) Before the test was supposed to start, though, I got an offer to start a union consulting gig back in Philadelphia, so I dropped out of the study before it started, and drove home to Philly. Otherwise, I stayed within an hour or two of Philadelphia… I did one in Delaware, one in Baltimore, and about five in Neptune, New Jersey… But I wasn’t a workaholic about it. I knew many guys, though, who would carpool a thousand miles at the drop of a hat, year after year.

MARK: How did you print that first issue of GPZ? Did you pay to have it printed, or did you find a way to scam it? I have this vision of you sneaking out of your bed, while participating in an inpatient study, sneaking down a darkened corridor, and breaking into an office to use the photocopier of a pharmaceutical company. Is that how it happened?

ROBERT: No… It was actually just as secretive, but far more complicated than that.

ROBERT: No… It was actually just as secretive, but far more complicated than that.

This brings us to another layer of the big onion. Remember, when you interviewed Pete Jordan, and he described the system that existed for scamming free services from Kinko’s? Well, to put it very mildly, it wasn’t just something that happened in the lives of a few isolated zine publishers. It was a huge affair, happening all over the country. I’d say, though, that Philly was either one of the biggest centers of it, or perhaps the biggest. My production of Guinea Pig Zero was just a tiny fraction of the operation. We had a guy who worked there, on the graveyard shift, for about two years, maybe more. During his shift, we brought in our own crew, sometimes up to about six people. By the way, our inside man at Kinko’s was the same guy who lost his marbles in that drug study, and who originally mused about making a guinea pig zine. Well, he calculated very precisely how much we could get away with. He strategized how to produce whatever we had in the queue, so we didn’t exceed the normal margin of waste of paper, which Kinko’s accounted for in its business plan. We produced many tons of pamphlets, flyers, posters, laminated cards, and zines. We even published 3,000 copies of Anarchism and the Black Revolution.

We would lay out a spreadsheet, and each person would do what they had the skills for. And, if they had no skills, they’d collate some regular Kinko’s job. If they could operate one of the machines, they would, either for a Kinko’s job, or for one of the anarchist jobs. And, at the end of the shift, the day manager would come in and be amazed by the huge amount of work that had gotten done overnight.

You’ve heard of Mumia Abu-Jamal? Well, he’s not only alive, and famous, but no longer on death row. Well, if not for the West Philly anarchists working through the wee hours of the night for several years, he’d be long dead and totally forgotten. And it wasn’t just quantities of paper. It was very fine graphic design as well. One reason why Mumia’s case got popular all over the world was because his face went from being an ink-smudge with a smile on it, to a real face, thanks to our work and the Kinko’s facilities.

We made our own stockpile of self-service copy cards for the cause. I had 4-inch tall bundles, all wrapped up in paper, with a $99 credit on each card. We gave them away to good causes all the time. All that went on for about nine years. In the thick of it, we refilled the self-serve cards at home. We worked all night, sometimes three or four nights a week. And the rear bumper of my van would scrape the pavement as we left the Kinko’s parking lot, throwing up sparks. I thanked that company in the acknowledgements page of the Guinea Pig Zero anthology. (I called it “Stinko’s.”)

MARK: I love the idea of Kinko’s playing an active, albeit unwanted, role in subverting the death penalty. That’s exactly the kind of unwritten history I was hoping to get at with this series.

ROBERT: Kinko’s had no interest in catching and prosecuting scammers like us, even when the store manager was sharp enough to figure it out. Many managers had scams of their own going on, and it would have been a disaster at the corporate level if the general public learned how easy it was to scam copies. Kinko’s was this inflated corporate behemoth that was a near-monopoly, and that’s what they relied on for dominating the market. They never had anyone arrested when they spotted the $99 cards. They would just confiscate the card, and sometimes banish you from that one store. This never happened to me. I’d just lay a hat or a book on the card reader and keep an eye on the staff if I happened to be doing work in the daytime.

So it was a balance of completely unrelated interests.The company wanted profit, but they could afford to ignore us, or not even look for us. We were doing our activism without needing to be paid, and we weren’t disrupting their operations. We brought Kinko’s all our business because the price was zero. They beat the price of all the brilliant, eco-friendly companies where workers were respected. To beat Kinko’s price of zero, you’d have to pay us and do the work too.

While we never tried too hard to get a union campaign started there, we did agitate a little. We’d sent union newsletters by email and FAX to hundreds of stores a night. It was great fun, and it lit a fire under a few asses. But it fizzled out, as most campaigns do. We reverted to not biting the hand that was feeding us.

MARK: How did GPZ evolve over time, in terms of content, focus, design, contributors, etc?

ROBERT: I laid out the pages of issues 1 and 2… and the last one, 8. My friend Alexis Buss designed all the covers, and the pages of the other five. But, in most cases, I got the images and artwork together for her. Twice I paid artists for the cover image. Those were issues 3 and 7. (Issue 7 was the best one of all, with a cover by Bruce Orr.) Issue 8 was done as a gift from my friend Maile Pickett, who was a serious activist in those days. For contributors, I preferred actual guinea pigs, but they had to give a good enough story. Once I ran a piece by a guy who pretended to be a guinea pig… I could tell, but I had nothing better at the moment, and it was short. And it didn’t say anything so wrong that it did any harm. Once I had to edit a piece so much that I was almost rewriting it, but it was important. Another major reason for the zine’s success was the general support of close friends, such as Alison Lewis. She’s the webmistress, plus she was a contributor, and always gave valuable advice.

MARK: Speaking of friends and collaborators, is there anyone else who comes to mind?

ROBERT: I have fond memories of Phil Buchanan, who lived in Indianapolis. He wrote in issues 5 and 7 about Eli Lilly’s sometimes raunchy research unit there. At first, his reports were anonymous, but later I used his name and called him my “Indianapolis Bureau Chief.” (The title was a spoof on how big news people turn themselves into mucky-mucks.) We used to spend hours on the phone with one another. Phil was in his forties, and dirt poor. He slept on the floor of his mom’s basement. His stories were great, and he was a really nice, intelligent guy. Finally, he got some weird cancer and died after not too many months. He had to scramble for pain medication that he couldn’t pay for. When I lived in Paris, I’d get advice for him from my sister Denise, who is a Nurse Practitioner. Unfortunately I never met Phil in person, nor even saw a picture of him. I wish I had, because his contribution to the GPZ project was a big one.

Only during this interview did I remember that “Randall Phillip,” the publisher of the zine Fuck and creator of Deceased Fetus Trading Cards, wrote a report card for GPZ. His zine was gratuitously disgusting, and, to read it, you’d assume that he was a psycho killer, or at least a total whack job. He also did one-man protests in front of abortion clinics. He did this not to harass the clients, but to ridicule the anti-abortion maniacs who would usually be elsewhere on the same street. I knew him well in West Philly, and he wasn’t even slightly crazy. Rather, he was the opposite. Randall’s stuff was free speech and pro-choice activism… if you could see beyond the pictures of miscarried fetuses with two heads. He would come along with us to Kinko’s sometimes and produce stacks of his zines and laminated cards.

MARK: Is there anything that you didn’t print, but you wish now that you would have?

ROBERT: A few times, for whatever reason, I was unable to get a great story into the zine. And I regret those instances. One was a story about a doctor who did extreme Ritalin experiments on his girlfriend (who I interviewed). He had gotten caught, decades earlier. That would have been huge if I’d finished it, in part because he was alive, and I’d located him on the west coast. The doctor’s name was Donald McCabe. He died in 2011, probably of old age. McCabe was an amateur artist, and that played into the story.

Another story was sent to me in a long, hand-written letter about the author wandering around in an abandoned state mental hospital, and it was really good.

MARK: I’m curious as to how McCabe’s being an artist figured into his experimenting on his girlfriend…

ROBERT: In the court case about the experiments, back in 1978, McCabe surprised everyone by surrendering all of his notes on the experiments, which included his drawings of the victim.

ROBERT: In the court case about the experiments, back in 1978, McCabe surprised everyone by surrendering all of his notes on the experiments, which included his drawings of the victim.

MARK: Do I understand correctly that you left the U.S. for a while?

ROBERT: I lived just outside Paris, in Noisy-le-Sec, France for two years (2003-2005). I intended to settle in France permanently, and I still miss the place. I ask myself what life would be like right now, had I stayed. At the time, though, I was living alone, and pretty poor. I felt isolated. That’s the short version. I decided to return to Philadelphia, and that’s what I did. But I did some of the best writing I’ve ever done in France. It’s a wonderful country, and I know it well… Because I was poor, I’d wanted to do drug studies over there, but my French was lousy, so the recruiters turned me away on ethical grounds. I gave up on the idea after a few tries… Fortunately, I got hired as a documentary film researcher. The film group had found me because they’d wanted to ask me about guinea pigging, and I ended up working for them. That was another huge adventure, by the way. I researched a documentary about the 1978 Jonestown tragedy. The story is so large, and so sad. To know it as well as I do changes a person. I was deeply affected by it. It also had me investigating a story that, until recently, carried the weight of conspiracy theories. When I started, I asked eyewitnesses about all that, but now – well, it’s just a bad joke. Anyway, I’m lucky to have learned the Jonestown story directly from people who were there.

MARK: You’re referring to the rumors that our government was involved in the killing of Jones and his followers?

ROBERT: Yes, that was the gist of the conspiracy theories. It was one thing to spin together these theories at the height of the cold war, but today, after tons of the old documents are available (thanks to the Jonestown Institute in San Diego) and loads of testimony has been given by people who had remained silent for decades, it’s a different thing. If you can still find anyone who believes that CIA-employed mercenaries killed people that night, then you’ve found an idiot. All of that bullshit derived originally from the lips of Jim Jones, in the lies he told his followers in order to make them afraid and to keep them under his control. It would be easier to know the Jonestown story if the CIA had had any role in the disaster. What actually happened is a million times more disturbing.

MARK: In retrospect, do you think that Guinea Pig Zero helped bring about any positive change with regard to how human test subjects are treated?

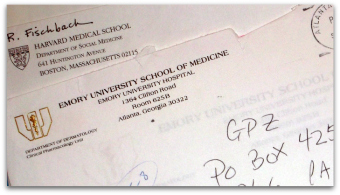

ROBERT: It did help. I can’t say what changed directly as a result of GPZ in terms of the way clinical trials are done, but the idea of guinea pigging as gainful employment had never been presented as well in a public forum before I came along. Even now, when I meet people in the pharmaceutical industry, they know about Guinea Pig Zero, every time. The Guinea Pig Zero anthology has been used as a teaching text in universities ever since it came out, and, back in the day, I used to send the zine to college libraries all over the world.

MARK: Did it ever cross your mind to try to formally unionize human test subjects? I image doing so would be next to impossible, given the itinerant nature of work, but I’m curious as to whether you gave it any thought, given your background.

ROBERT: I’ve been asked this ever since the beginning, and the answer is very simple. To organize paid volunteer guinea pigs is an idea that people would only have if they’d never organized before. First, paid volunteer research subjects are self-employed contractors, not employees. As such, U.S. labor laws don’t even apply to them. Second, they’re scattered in tiny groups, or individual situations, to the point of being atomized. This means that people who had never even seen each other’s faces, would have to take risks together, when most guinea pigs don’t even do this work as their primary source of income. The pros, who do rely on it, have to scam the system in order to do as many studies as possible, so, if they turned into “employees,” they’d have to “go legit” and come onto the legal radar. And this would be financial suicide.

The most important reason why there will never be a guinea pig union, though, is because U.S. labor law, if applied to guinea pigs, would diminish the rights and protections that they have as sort-of patients, sort-of experimental subjects. It would disempower them. The general buzz that exists about guinea pigs in the media, including the existence of my zine, creates a shared culture and an awareness of one another, and that has real meaning, but trying to create a labor union of human guinea pigs is a waste of time. Any experienced union organizer would tell you the same thing.

MARK: Were there attempts to keep you out of the industry? Was it ever brought to your attention, for instance, that your photo was being circulated within the clinics where this kind of work was being done at the time?

ROBERT: When they realized that I was Guinea Pig Zero, the staff of a given research unit would make a decision as to how they felt about my writing. I got different reactions in different places. At a few places (e.g. University of Pennsylvania), I was told that I was considered a journalist, and, as such, having me participate would compromise the privacy of the other subjects. But, at the best units here in Philly (Jefferson Hospital and Wyeth-Ayerst), where I wanted to keep doing studies, they were cool. The staff at Jefferson actually had special rules pertaining to me. My zine could not be in the nursing station, and the staffers weren’t allowed to buy the zine from me while in the unit. This was perfectly fair. I shouldn’t have been treated like a VIP. And I took it as a huge compliment.

ROBERT: The idea for the zine’s title, which was my nom de plume in the first two issues, was loosely based on “patient zero,” the wandering rogue AIDS sufferer who upset scientists by having his own agenda. It was also influenced by secret agent mythology… how an agent, like James Bond, would be given a number. My favorite, was Agent 355, George Washington’s ultra-secret female operative in New York. Even today we don’t know her identity. She was incredibly brave, extremely smart, probably quite beautiful, and she saved the American Revolution in no uncertain terms.

MARK: What’s your favorite GPZ story?

ROBERT: The one I feel gave me the most delight was the one about Alexis St. Martin. The best one by a contributor was “Awake With A Vengeance,” by Donno Layton. The most important were the two about the case of Jesse Gelsinger, one by me and the other by Jesse’s father Paul. His article could easily have been published in a major newspaper or magazine, but Paul Gelsinger chose Guinea Pig Zero. That really floored me.

MARK: Do you mind if we take them one by one, starting with the piece about Alexis St. Martin? What did that piece in particular delight you?

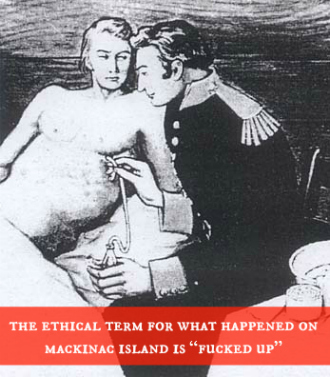

ROBERT: Alexis St. Martin is probably the most famous human guinea pig in the history of medicine, because Dr. William Beaumont used his body to determine how the human stomach digests food.

MARK: He’d been shot at close range, leaving a hole in his side, through which Beumont could observe his digestion, right?

ROBERT: Right, but when the emergency was over, the surgeon should have closed up the hole. This guy, Beaumont, made the hole permanent, though, so that he could continue his digestion experiments. In ethical terms, this is called “fucked up.” And all of the descriptions of Alexis left him looking like an asshole. My article turned that around, and became the definitive, and most thorough, article ever written about St. Martin. I was, and I still am, proud of that article.

MARK: Why did people think that he was an asshole? And how did you disprove that commonly held belief? Did you find diary entries of people on Mackinac Island, where this happened, saying, “Alexis isn’t an asshole”?

ROBERT: Everyone who had written about Alexis since the 1820s had done so solely because he was part of Dr. Beaumont’s story. Alexis was an illiterate dirt farmer, a French speaking Catholic, and a very poor young man. Beaumont was the opposite in every way. When I stepped in and wrote about Alexis, I had to look at all the existing information and point out what I felt was obvious. His life was completely changed by Beaumont’s experiments. The hole in his stomach never needed to exist. It was there because it benefited Beaumont and his research. The big, miraculous contribution to the world was that Alexis was so generous with himself, not that Beaumont was an excellent doctor.

ROBERT: Everyone who had written about Alexis since the 1820s had done so solely because he was part of Dr. Beaumont’s story. Alexis was an illiterate dirt farmer, a French speaking Catholic, and a very poor young man. Beaumont was the opposite in every way. When I stepped in and wrote about Alexis, I had to look at all the existing information and point out what I felt was obvious. His life was completely changed by Beaumont’s experiments. The hole in his stomach never needed to exist. It was there because it benefited Beaumont and his research. The big, miraculous contribution to the world was that Alexis was so generous with himself, not that Beaumont was an excellent doctor.

Speaking of Alexis, I was contacted by one of his descendants, and she gave me a photograph of him and his wife that had never been published before. Communicating with descendants has brought some of the most thrilling discoveries in my research over the years.

Anyway, Alexis St. Martin was a very cool person, and a hero of medical history. I was the one who made that clear. Before me, Alexis was this wretched, ungrateful, and morally doubtful person who had accidentally become part of the Beaumont story.

MARK: “Alexis St. Martin allowed the experiments to be conducted,” according Wikipedia, “not as an act to repay Beaumont for keeping him alive, but rather because Beaumont had the illiterate St. Martin sign a contract to work as a servant.” I don’t imagine that contract still exists, does it?

ROBERT: No, its existence is known from correspondence and journal entries of Dr. Beaumont, as I recall.

MARK: I don’t recall “Awake with a Vengeance.” What was that one about?

ROBERT: Donno Layton was working at the nearby video rental place in those days, and he was learning the tattoo trade. We’d both heard about sleep deprivation studies being conducted at the University of Pennsylvania, and we signed up, maybe a few weeks apart. Fortunately for me, Donno finished his sleep study first, and wrote an article about it. He gave me the piece when I was still in the early stages of the study, before I’d been confined… before they shut off all communications. His description of going insane, over an 88 hour period, from lack of sleep, was so funny and well-written that I had no need to put myself through the torture to get the same story.

MARK: So it wasn’t always strictly about the money, then? You took some jobs primarily because you thought that result might be story-worthy?

ROBERT: Well, in that case, I certainly wanted the story more than money. I also had a lot on my plate then, and I didn’t want to be out-of-touch for the several days it involved. Usually it was just for the money, though. Another time, I’d wanted to go to the Johnson Space Center in Texas for a bed rest study. It only paid pennies, but I wanted to get the story. But they spotted the zine and I never went down there.

MARK: What do you mean by, “they spotted the zine”?

ROBERT: They somehow connected my name, when I was speaking to them by telephone, to the person who was publishing Guinea Pig Zero… on the internet, or by word of mouth, I don’t know. It must have seemed peculiar to them that I wanted to go all the way from Philly to Houston for such extremely low pay, to work a tortuous, ultra-shity job. I wasn’t too surprised when they spotted me.

MARK: What were you criteria for choosing or not choosing a particular study?

ROBERT: The best study is one where the pay is high, the food and accommodations are at least decent, and you take a drug that you don’t even feel or notice. Psych drugs are off my chart because they defeat the point. I want to get paid while my body works, keeping my mind free for other things. Psych drugs monopolize your mind, so the drug study becomes like most jobs, where you give 100% of yourself to it.

MARK: Jesse Gelsinger, for those that don’t remember the name, died at the University of Pennsylvania in 1999, at the age of 18, as a result of having participated in a clinical trial. He suffered from ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency, an X-linked genetic disease of the liver, which is usually fatal at birth. He’d apparently gotten it later in life, as a result of some kind of gene mutation, and researchers were testing a gene therapy on him. The hope was to create a drug that could be used to treat infants. But, according to an investigation after the fact, several rules were broken in this case. Is that right?

ROBERT: The chief investigator was financially invested in the outcome of the experiment, they had an in-house bioethics professor signing off on the project, and they mishandled the blood and tissue samples. Worse, they tweaked the chemistry of Jesse’s blood in order to make him qualify for the experiment, which put him in danger according to the protocol that they themselves had written. And, worst of all, they lied to Jesse and his father about how the experimental treatment was improving the condition of other subjects in the experiment.

With all these very wrongful things happening at the same time, I wrote that it was a case of manslaughter, which it certainly was. But the New York Times and many other periodicals were following the story and never used the word manslaughter, because it would have precipitated a lawsuit. Interestingly, the Philadelphia Inquirer stayed away from the whole thing and ran university-friendly op-ed pieces. The student paper, though, The Daily Pennsylvanian, ripped the researchers new assholes.

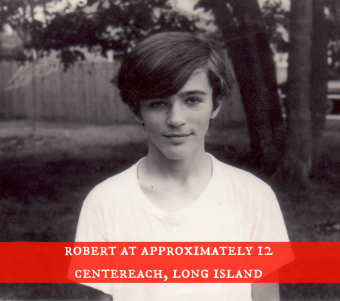

MARK: Where did you grow up? And what were you like as a kid?

ROBERT: I grew up in Centereach, Long Island. My neighborhood was surrounded by woods when I arrived as a five year old in 1963. But the woods disappeared as I grew up. My childhood was fairly idyllic, I suppose. It certainly was in comparison with most kids growing up now. I was into chess. I read a lot. I read Homer and Tolkien in elementary school. My Mom used to read when my sisters and I were in school, and tell us all about the books she’d read when we came home. I took in Will Durant’s 10-volume Story of Civilization this way – second-hand. As a teenager, I became an alcoholic, but I stopped drinking at age 22.

ROBERT: I grew up in Centereach, Long Island. My neighborhood was surrounded by woods when I arrived as a five year old in 1963. But the woods disappeared as I grew up. My childhood was fairly idyllic, I suppose. It certainly was in comparison with most kids growing up now. I was into chess. I read a lot. I read Homer and Tolkien in elementary school. My Mom used to read when my sisters and I were in school, and tell us all about the books she’d read when we came home. I took in Will Durant’s 10-volume Story of Civilization this way – second-hand. As a teenager, I became an alcoholic, but I stopped drinking at age 22.

MARK: What made you stop at 22? Most people, from what I’ve experienced, need a little more time to come to the realization that they need to stop?

ROBERT: Briefly stated, it was either stop or die. It totally altered my early life.

MARK: Where were you at the time?

ROBERT: I still lived in Eastern Long Island, with small periods in Brooklyn and Queens.

MARK: So, how’d you come to be in West Philly?

ROBERT: I moved to Philly in 1983 because my then-girlfriend was from there. Nothing was happening on Long Island to keep me there and I found Philly very interesting. We got an apartment in the far Northeast (at the edge of the city, more suburban than city living) and I enrolled in Temple University. I did a “junior year abroad” in Rome, Italy, and then another in Visakhapatnam, India. After India (summer 1989) I returned to Philadelphia, looking for a place, and a friend was living in West Philly, so I took a room in the same house. That’s when I started meeting anarchists and union organizers. Since then, life has been most interesting. I feel correct in saying that I became an adult at that point.

MARK: Do you still identify as an Anarchist?

ROBERT: Yes. That will never change, as I was in my thirties when I started to identify as such. People who discover it as a kid can feel that they’ve passed into another phase of life and just leave it, but, for me, it’s part of being an adult. I’m getting back into local anarchist historical research too. I’ve made some serious connections over the past few years.

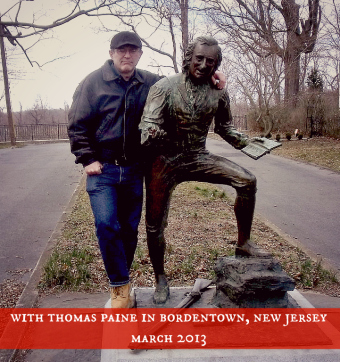

But I should say that I spend more energy thinking about being an atheist and freethinker now. Lately, I’m more and more interested in the way the memory and the legacy of Thomas Paine has been suppressed since the 1790s in the United States… especially here in Philadelphia. We have a huge bridge and a museum for Betsy Ross, who is rumored to have done something completely irrelevant, but virtually nothing for Thomas Paine, whose writings literally won the war.

Anarchism is sort of built into me, and I don’t need to think about it all the time. It’s like my race or my gender. I’m white, male, and anarchist.

MARK: What should people know about Thomas Paine, in your opinion?

ROBERT: Tom Paine wrote pamphlets that defined the American Revolution, and, in so doing, he transformed the war from a hopeless mess into a victory. Nobody else did that. His legacy has been suppressed because he wrote, in The Age of Reason (1794): “I do not believe in the creed professed by the Jewish church, by the Roman church, by the Greek church, by the Turkish church, by the Protestant church, nor by any church that I know of. My own mind is my own church.” So, ever since, the religious bigots have smeared him, ostracized him, and kept him from the honors that he deserves. It goes very deep when you look further in, and it’s glaringly true and undeniable. All over the U.S., there are major airports, bridges, highways, universities, and whole cities named after people who, in terms of historical importance, are mere ass-wipes in comparison to Tom Paine. But, in Philly, where the hero patriot lived and wrote, a statue of Paine in a park was once vetoed by City Council because it might “offend passing Christians.”

Anyway, I’ve been bitching about that lately. It makes my blood boil. It’s a national disgrace.

MARK: I’ve always been curious about Paine and how he managed his printing. Was he just a wealthy guy? Or did he have a benefactor? Or was pamphleteering a legitimate and profitable business? I feel as though I should know, but I don’t.

ROBERT: Tom Paine was a working man. He had been a civil servant in England, but, when he came to America, his writings started selling well. They were game-changing – extremely popular bestsellers. But Paine gave all of his earning from his pamphlets to the cause of the revolution. He made nothing from them. Here he was, the author of the bestselling pamphlets of his century, and yet he had to ask Congress for a living stipend, so that he could continue writing in support of the war effort. Not only did he not get the money from the sales, but, if the King’s men found him, he would have been tortured and hanged, for this same writing. It was a crazy arrangement.

ROBERT: Tom Paine was a working man. He had been a civil servant in England, but, when he came to America, his writings started selling well. They were game-changing – extremely popular bestsellers. But Paine gave all of his earning from his pamphlets to the cause of the revolution. He made nothing from them. Here he was, the author of the bestselling pamphlets of his century, and yet he had to ask Congress for a living stipend, so that he could continue writing in support of the war effort. Not only did he not get the money from the sales, but, if the King’s men found him, he would have been tortured and hanged, for this same writing. It was a crazy arrangement.

Aside from writing the words that won the war, Thomas Paine was a warrior in the army. He refused a commission, insisting that he’d rather stay with the men. Not only did this mean that he earned lousy money, but he also didn’t get a horse. He had to march during the campaigns he was involved in. We’re talking about hundreds of miles, carrying a pack and a musket. At Trenton and at Fort Mifflin (a few miles from me), Paine braved cannon fire.

There have been very, very few people whose work and sacrifices toward a good cause have achieved so much, in all of human history, as those of Thomas Paine. And this country’s response is to treat him like shit. Those who would deny what I’m saying, or who think he deserves this treatment, are religious bigots and freedom-hating rats. Paine was the only American patriot of high stature who was not a rich man, and not university educated.

And Paine’s critics tell yarns about him drinking too much. It’s completely weird how the report of alcoholism works. Paine was a guy from England who, from what I can tell, drank the usual amount of beer. There is no other evidence. But people like to say that he drank too much. Conversely, it you go through the little museum-house where Edgar Allan Poe wrote The Raven, and the tour guide will tell you, “We’ll never know exactly what happened when Poe got off the train at Baltimore…” We all know that the great poet very publicly drank himself to death, and they don’t mention it at all. As one who has come close to doing exactly that, this is a very big deal to me. If he had not been a boozer, Poe might have become as huge a literary figure as Shakespeare – he wrote that well. In Paine’s case, the reports of drunkenness are invented, whereas, in Poe’s case, they’re withheld. It just depends on whether the historical figure in question is being condemned or celebrated.

MARK: Do you suffer from any long term adverse effects as a result of the work you’ve done as a human test subject?

ROBERT: No. I avoided studies that seemed dangerous, especially psychiatric drug trials. By the way, I’ve been asked this question thousands of times and it always reminds me how tempting it can be to exaggerate or embellish these off-beat stories of guinea pigging. Once I was on This American Life with Ira Glass, and I could have really opened up a can of worms because they wanted something different, something juicy. But I never cared about being sensational as much as I wanted to be ready to debate cases with doctors and their lawyers. The big adventure with Harper’s Magazine galvanized me on that point.

MARK: What happened with Harper’s?

ROBERT: Harper’s was sued by a hospital company and threatened with one by SmithKline Beecham because they reprinted my unfavorable “report cards” on the research units they owned. I was co-defendant with Harper’s because I wrote the material. In the end, I was very clearly in the right, and Harper’s looked bad because they sold me out, caving in to the pressure. The hospital company (Allegheny) imploded in a huge and scandalous bankruptcy debacle. Harper’s printed the first and second “apology and clarification” statements in all their 150 years, but they wore egg on their face as a result of the apologies, once I was vindicated.

MARK: How many tests have you participated in over the course of your career as a test subject?

MARK: How many tests have you participated in over the course of your career as a test subject?

ROBERT: The number I’ve settled on is seventy-five or eighty. It’s probably as accurate as I’ll ever get, but I didn’t keep a careful record of each one.

MARK: Was there good money in it back in the day?

ROBERT: The usual rate was $200 per day, for each whole day in a study. I decided that was the going rate, but it was much lower in some parts of the U.S.

MARK: Assuming you keep an eye on the industry, how’s it different today from when you started, in terms of pay, the kinds of research being done, the treatment of human test subjects, etc?

ROBERT: I don’t really keep track of the industry anymore. When a big story comes up, I read about it, but it’s been a few years since I’ve collected information on a case. I don’t feel the urge to write about what I don’t know, so, now that I’m not doing studies, the GPZ project is over.

MARK: Do I understand correctly that, a few years back, you were involved in a documentary film project. What was that about?

ROBERT: Yes, it’s called Off Label, created by Mike Palmieri and Donal Mosher, released in 2012. It was the last of the film projects I’ve been involved in as GPZ, and it’s a world ahead of all the others. The film was inspired by the writings of Carl Elliott, the Bioethics professor at University of Minnesota. Carl is a knight in shining armor in the Bioethics world. There are a few others, but he has done the most.

When Mike and Donal first came to Philly and interviewed me, I immediately saw that their project was picking up where I had left off when I put my zine to bed. They already knew almost all the people I recommended to them, whereas most filmmakers had done about half a day’s reading before they get to me. I’m talking about dozens of filmmakers, for both documentaries and fiction films, a few of which were finished. One had me as a character (with my name) in a quirky adventure film with a romance between a lab rat and a nurse. That one was a script that was sent around Hollywood, and it was quite well written. Another time I got an option with money paid to me. Two of the unfinished documentaries went as far as taking footage and making short proposal videos to show to studios.

The years when Off Label was in production, and when Carl Elliott was interviewing me for articles, were in a period when I was not at my best, for reasons I’ll just leave out. My involvement contributed well to their work, but I regret that my work with such stellar people did not give them all of what they would have gotten if our paths had crossed now, or a dozen years ago. The results would have been well amplified.

MARK: What was the worst test that you were ever involved in?

MARK: What was the worst test that you were ever involved in?

ROBERT: It was in Neptune, New Jersey, in a relatively large unit. The accommodations were so lousy that you couldn’t really sleep or get a hot shower. Some of the guinea pigs were jailbird types, and the food was just shit. This was the study where my blood pressure dropped so low that I passed out and my face fell into the salad that I was eating. But I never suffered harm or got badly scared in the course of a study. Once, I almost suffered harm, but I only got the placebo.

MARK: What happened?

ROBERT: It was a study at Wyeth-Ayerst, here in Philly. My dose of the drug wasn’t prepared in time, due to a heavy rain storm. The man whose job it was to mix it was blocked by flooding. He arrived a few minutes late, which meant they couldn’t give me the dose. It was a decades-old heart attack drug called Ameoterone. The guy in the bed next to me had gotten it earlier as an injection. He told me that he felt it rush along his veins and up to his head. It felt like he was being brained with a 2×4, he said. He had bruises from the stuff. My dose of the drug would have been as a drip, from a bottle. As the guy was late, though, I just got a water drip (placebo). This other guy had gotten the drug in the injection and water in the drip. We were getting $450 per day, and it lasted about four days. I just kicked back the whole time and got full payment. The other guy really earned his cash.

MARK: Just now, having taken a break from our interview, I jumped over to Reddit, where the first thing I saw was an interview with a survivor of Nazi medical experimentation. The woman, Eva Mozes Kor, is the author of Surviving the Angel of Death: The True Story of a Mengele Twin in Auschwitz. Truly horrific stuff. By noting this, I’m not trying to suggest that modern clinical trials are in any way equivalent to the work of the Nazis, but, when I saw her use the phrase “human guinea pig,” there was a moment where I made the connection, and realized that your experience as a human test subject exists on the same continuum as hers. And the same is true of the those black sharecroppers, in 1932, who were unwittingly made part of the Tuskegee syphilis experiment. Did you, back when you were a human test subject, give any thought to that continuum, and your place on it?

ROBERT: I agree that this continuum exists, but I always try to be clear about where my experience comes in. I was a healthy, normal control subject, working as a paid volunteer in the U.S. after the prisoner experiments were abolished. As such, I was not in much danger for the most part. People in the same situation that I was in do suffer harm or die, and the legal teams of the research institutions make most of that disappear from History. Still it does not morally compare to someone who was forced, as a prisoner or as an oppressed citizen who was totally deceived, to serve as experimental flesh. In the case of Tuskeegee the experiment was conducted for purely racist reasons anyway.

I had a weird little way of paying my bills as a working class American in the 1990s. My job was less dangerous than many other, common jobs. Those other guinea pigs were lied to, tortured, and murdered.

MARK: Did you ever do a drug that made you feel better to the point that you missed it once the trial was over?

ROBERT: No, definitely not.

MARK: Is there anything that you’d do differently, if you were to do it all over again?

ROBERT: I would change the way I moved around. I moved more than I needed to. I wish I’d kept a more stable living situation so that I would be more productive as a writer. With a few errors not made, I would be the author of half a dozen more books by now.

MARK: What are you doing these days?

ROBERT: For money, I paint and repair houses. I have three cats, and I’m trying to get back to the writing. I feel it coming back. It’s a quiet winter, this.

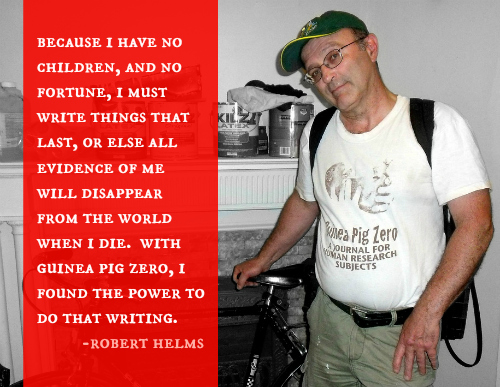

MARK: What’s the best thing to come from the GPZ experience?

ROBERT: I took a strange and lousy job and turned it into a public discussion, and a personal adventure, all by my written words. That was how I discovered the most important thing in myself. Because I have no children, and no fortune, I must write things that last, or else any contribution I have made will disappear from the world when I die. With Guinea Pig Zero, I found the power to do that writing. This discovery was the best thing to come from the zine.

[note: If you like what you’ve read and want more about the American underground press and the people behind it, be sure to check the other interviews in the History of Zines series.]

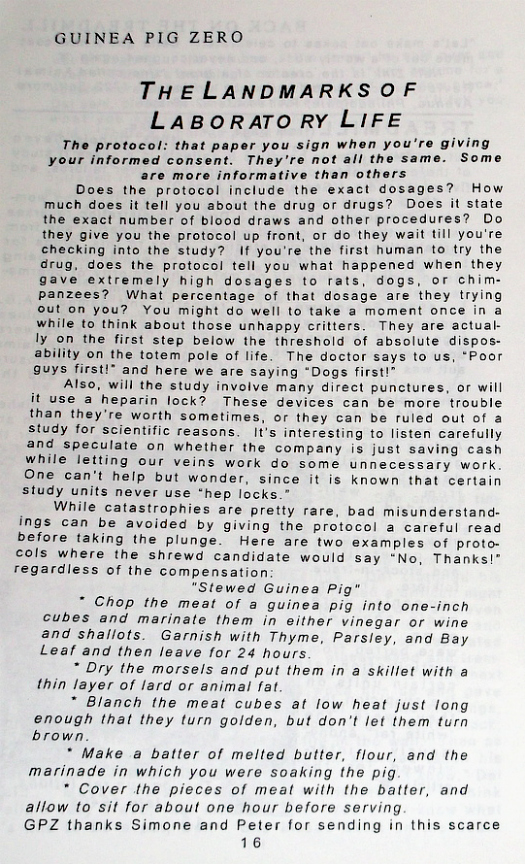

update: For those of you who have never had the pleasure to have held a copy of Guinea Pig Zero in your hands, here’s a story from the first issue, titled The Landmarks of Laboratory Life.

You’ll find the rest of the story here: page 2, pages 3 & 4, pages 5 & 6, pages 7 & 8.

10 Comments

Damn you. I’ve wasted the past two hours knee deep in Jonestown conspiracy theory because of this post.

If you care to join me, you can do so here.

http://www.ratical.org/ratville/JFK/JohnJudge/Jonestown.html

A lot of friends used to be lab rats at Pfizer, back in the 90s. I’d always wanted to do it, as it seemed like easy money, but, every time an opportunity presented itself, I chickened out. What my friends told me about the contract language really scared me.

I’m going to be on Mackinac Island this summer. Does anyone know if there are still any artifacts there from St. Martin? If so, I’ll take photos for you.

Great interview. The image of Beaumont and St. Martin, though, looks like gay porn.

Am I reading the text above McCabe’s drawing of his girlfriend correctly? Does it say, “All I think of is killing myself”? He fed her Ritalin until she was suicidal?

McCabe INJECTED the Ritalin into her.

One wonders what Thomas Paine would make of this discussion.

Perhaps of interest on Reddit right now.

“IamA Human Guinea Pig Getting the Newest Ebola Vaccine AMA!”

http://www.reddit.com/r/IAmA/comments/2gnn1r/iama_human_guinea_pig_getting_the_newest_ebola/

This is the only post with the tag “experiments.”

Presumably, all of the other posts are real.

According to Robert, today is the 20th anniversary of the first issue coming out.

“I can hardly believe that twenty years ago today, I released the first issue of my zine Guinea Pig Zero. The project has given me so many cherished memories. When I think about it I get lost in thought.” – Robert Helms

3 Trackbacks

[…] Your name has come up in a few interviews that I’ve done in this series. Most recently, Robert Helms, the publisher of Guinea Pig Zero, was telling us about your activities in the Pennsylv… prior to the launch of the TempSlave. As I wasn’t aware of that part of your history, perhaps we […]

[…] friend Robert Helms, the editor of the zine Guinea Pig Zero, reminded me of this fact today, when he forwarded a link […]

[…] Pete Larson. He played a few metal riffs on his guitar and we were off. The next call was from Robert Helms, the editor of Guinea Pig Zero, who’d called in to talk about Thomas Paine, and the fact that […]