Upon graduating the University of Michigan with her PhD in Biomedical Engineering, Michelle Leach decided to try something different. Instead of either pursuing a careen in academia, or accepting a job in industry, she chose to start a social venture called Oasis Aquaponics with the intention of creating an affordable food production system that could dramatically improve the quality of life for poor families in Central America. Now that her third generation prototype is about complete, thanks in part to a grant from the Ann Arbor Awesome Foundation, I thought that I’d check in with her and see how things were going.

[above: Michelle Leach and Jacquelyn Hernandez Ortiz in El Salvador, in front of Mt. Guazapa, surrounded by the ubiquitous corn that dominates the local diet.]

MARK: When discussing the Oasis Aquaponic Food Production System with someone for the first time, how do you describe? Or, to put it in entrepreneurial terms, what’s your elevator pitch?

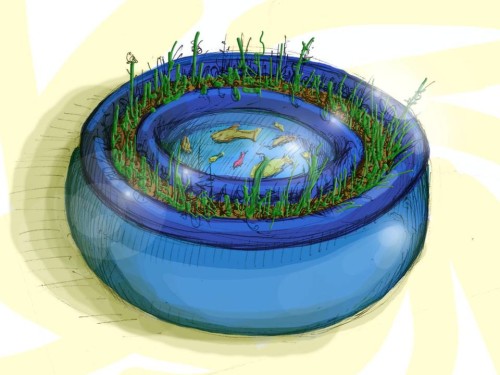

MICHELLE: Food insecurity is the constant companion of the poor. Our solution, The Oasis, is a solar-powered inflatable aquaponics system capable of producing at minimum 300 pounds of Tilapia and 600 pounds of tomatoes, or other vegetables, annually. With a projected retail price of $100, and a business model that provides low-interest purchasing credit, our system is radically affordable and accessible.

MARK: How did the idea for the Oasis Aquaponic Food Production System come about?

MICHELLE: Two years ago, my friend Jacquelyn Hernandez Ortiz was finishing up her agricultural engineering degree and needed a senior thesis project. (Jackie was one of the Salvadoran students who received a college scholarship from my church.) Jackie asked me to help her brainstorm, and it just happened that I had recently stumbled across an article on aquaponics online, so I suggested the technique to her. Neither Jackie nor her professors had ever heard of aquaponics. I assisted them with locating some literature in Spanish on the subject, although there wasn’t much available. Jackie and her student teammates had great success with their senior thesis project, which resulted in a prototype barrel-based system. Jackie graduated, got a job with a local non-profit in El Salvador, and continued building the barrel systems with women in five remote villages in her general area. She and I then collaborated to increase the size of the system and moved to a brick tank-based design. This substantially increased the system’s production capability. However, the systems were still too expensive to sell. So we designed the Oasis with ultra-affordability in mind.

[above: The first prototype: a barrel based system]

MARK: And you, if I’m not mistaken, are spending a good deal of your time in El Salvador now as well, working with Jackie, correct?

MICHELLE: Yes. Jackie meets with the women who have barrel systems on a semi-regular basis to resolve any problems they may encounter. A subset of the women are also working on a larger system that they operate on a cooperative basis with Jackie in town. I do weekly water testing on the 31 brick systems, as well as chat with the family operators to address issues and try to glean more insight. I also have several more experimental-type systems running, which I monitor on a day to day basis.

[above: The second prototype: a brick tank system]

MARK: For people who might not be familiar with aquaponics systems, can you give us a brief overview on how the various components work together?

MICHELLE: Simplest explanation: The fish feed the plants and the plants clean the water. More detailed: The water pump draws water from the fish tank up to the gravel grow beds. Fish waste is suspended in this water and the gravel acts as a crude filter, as well as physical support for the plant roots. Bacteria living on the surface of the gravel breakdown this waste into a form of nitrogen which plants can uptake. The water draining out of the grow beds falls back into the fish tank, oxygenating the tank a bit in the process. Then the cycle repeats.

MARK: How has the $1,000 Ann Arbor Awesome Foundation grant helped?

MICHELLE: The money has all gone toward prototyping.

MARK: So, where are you with the next generation prototype?

MICHELLE: I hope to have prototypes ready to go in El Salvador by the end of February.

[above: Third generation Oasis prototype]

MARK: It’s probably worth noting that you, by training, are a biomedical engineer. Is that correct?

MICHELLE: Yep, undergrad, masters, and phd, all at U of M. My thesis focused on biomaterials for repair of trauma to the peripheral nervous system. I’m working on totally different stuff now – and yet sustainable agriculture has a similar base of knowledge – biology, engineering, the health of the product, producer and the environment, etc.

MARK: I’m curious as to why you chose to go this route instead of seeking out a post doc. Had you, earlier in your career, been planning to go into academia? If so, why the change in course?

MICHELLE: Yes, my plan had been to continue in academia, but I became rather disenchanted with it all. Particularly in my postdoc work it became apparent that I was spending all my time building million dollar devices that might one day benefit a couple of millionaires. It struck me that there were far more basic problems afflicting far more people that still needed to be addressed. I initially chose biomedical engineering because I wanted to use science and engineering to improve quality of life. I have not deviated from that course.

MARK: Would it be fair to say that, while a lot of work has been done in the area of aquaponics, up until now, there hasn’t been a lot of scientific research in the field? I mean, a lot of people are building systems, but, to my knowledge, not a lot of trained research scientists, like yourself, have taken on the problem in a systematic way that might yield reproducible results, right?

MICHELLE: Yes, this is one my peeves. There are a ton of backyard hobbyists, who are producing systems that seem to work, but they lack controls. It also seems like a few commercial operations are doing well, but they guard their systems like trade secrets. The few scientists who have done work in the area are using systems which are incredibly complicated/expensive and unsuited for the developing world. No one is doing well-controlled research on SIMPLE systems. This is the hole I’m trying to fill.

MARK: You said this was one of your peeves. Are there others as relates to this new industry you’ve entered?

MICHELLE: Sure, I suppose. The idea that the solution to poverty is a ‘thing’ or device is also somewhat misguided. People aren’t poor because they don’t have an Oasis, or a water filter, or a solar panel. People are poor for a host of other systemic reasons, which include poor infrastructure, corrupt governance, non-functioning legal frameworks, etc, etc, etc. But an Oasis, or a water filter, or a solar panel can make poverty less severe while big systemic changes happen slowly. We can use ‘things’ to chip away at the effects of poverty, and in the process empower the poor to demand systemic change.

MARK: There are other aquaponic systems on the market. How is the Oasis system different?

MICHELLE: The Oasis is designed to be radically affordable and large enough to produce a substantial quantity of food. Other systems are either extremely over-priced or too small to make a dent in a family’s nutritional requirements.

MARK: How is the system being received by those currently using the prototypes in El Salvador? Is it, as you had intended, changing people’s lives for the better? Are they providing useful feedback?

MICHELLE: The systems are being very well received. While everyone to date has received their system free of charge, we only provided alevin (baby fish) and concentrado (fish food) for the first crop cycle. It is up to the families to purchase these items for subsequent crop cycles. So far no systems have been abandoned. We see this as evidence that the families find the systems valuable. We have had some trouble getting ‘straight’ feedback, though… Everyone is super polite to me, and I was getting suspicious that perhaps I wasn’t hearing the whole story. So I recruited a local person to do anonymous interviews. We got some good data, which we are still working to translate and compile, but our preliminary read through suggests everyone is happy with the systems. We did, however, identify some small issues to address that hadn’t been on our radar.

MARK: What kinds of small issues? I’m curious.

MICHELLE: The operators compare the size of their fish to those of their neighbors. They attribute this to a difference in quality of alevin. The truth is that most of this inter-system variability is from different degrees of operator error. I wasn’t aware how little the operators understood about overfeeding resulting in excess nitrogen, resulting in stunting. Looking at it now, it’s rather counter-intuitive. For most animals, more food = more growth. In this case, though, too much food is very detrimental. And we need to do more education to drive this point across. I’m also going to create a kind of ruler scale that can be transferred onto a Coke bottle so that users of the system can make their own ‘measuring cups’.

It also came across how different operators are picking up small ‘tips and tricks’ that need to be shared with the group. We are going to try to convene them more often to share lessons. Stuff like: Make sure kids aren’t throwing rocks in to startle the fish, they will get sucked into the pump. If your dog is inexplicably soaked on hot days, it’s because he’s going swimming in your system. Just because you don’t see birds or garobos (local iguana-ish things) in your yard doesn’t mean they aren’t robbing you blind when you’re out of sight.

[above: Tilapia – about mid crop cycle]

MARK: You mentioned above that you were considering a unique financing system that would allow people to purchase these systems more easily. What do you have in mind?

MICHELLE: It would be a microloan with the system itself as the collateral.

MARK: I’m curious about your price point of $100 per unit. Do you think that’s sustainable? First, do you think you can produce and deliver the Oasis system for that amount? And, second, can you make enough to sustain a company, investing in sales, R&D, customer support, etc.?

MICHELLE: We see ourselves as really having two markets. Farmers in the developing world and aquaponics enthusiasts in the developed world. The price point in the developed world will be higher. Also, the amount of infrastructure we will be building in the developing world will be minimal.

MARK: Have you thought about your distribution channels yet? Is there an existing infrastructure of some kind that you can perhaps piggyback on?

MICHELLE: Distribution in the developing world is tricky and absolutely must piggyback on the informal systems already in place. For example, Coca Cola stopped driving trucks around El Salvador years ago. However, you can still get a $0.40 Coke on the side of any mountain in any tiny remote village. Why? Because an informal distribution network of village shopkeepers and mid-size wholesalers exists. The only distribution method that works is local people selling locally. It is very much the Wild Wild West with the village General Store. The shopkeeper becomes like a car dealer – a subject matter expert, a repair shop, etc all in one. We won’t develop a large sales and customer support network, rather we will fit into the one that already exists.

MARK: The last time we spoke, we discussed your long range plans to start collecting data from users, having them weigh the fish harvested, the produce grown, etc. Have you made any headway toward putting together a research plan that will yield hard data?

MICHELLE: For now, I think our initial pilot with The Oasis will be run by Jackie herself. It is very important that we get accurate data. We will have a small number of systems (2-3) at first, so it won’t be too much for her to manage.

MARK: So the idea is to have two or three units, side by side, so they’ll have the same sunlight, rainfall, etc… and then collect detailed data on the output of each system in terms of fish and vegetables produced… Will all of the units be exactly the same, or might one, for instance, have a different species of fish, or peppers instead of tomatoes, or a different kind of pump circulating the water, so that you can begin making comparisons that might help you to optimize the system?

MICHELLE: Yes, that’s the idea. For now, I am envisioning the systems identical with the exception of the power units. At least one will be on grid, and the others will have the option to be switched to the grid if the solar systems aren’t cutting it. (The grid is very stable where we are, and I have some doubts about the cheap components of the solar system). We will load the three with different amounts of fish (all tilapia) and try to keep the number and type of plants more or less constant.

MARK: Can you quantify how impactful a system like this might be in the life of a family in El Salvador? Do you have anecdotal data from those you’ve been working with thus far?

MICHELLE: Very impactful. Whole tilapia sells in the market at $2/lb. Tomatoes are $0.60/lb. A family that produces 300 lbs of fish and 600 pounds of tomatoes, that sold every bit of produce, could cover their costs and still net around $900 a year. In a country where a family is lucky to bring in $500 per person, per year, this can have an enormous impact. (Hard physical labor nets $1 per hour, when you can find it.) And all this from a system which only requires 15 minutes of attention daily.

6 Comments

It makes me happy to read stories like this. There are too many terrible things in my news feed today. It’s good to know that there are people out there trying to make a positive difference.

SOOOOO Awesome!

Michelle, thank you for doing this important work. Is there a site where you will be publishing your research findings?

I love companies, like Tom’s (http://www.toms.com/improving-lives), that channel their profits earned in the so-called developed world into helping people around the globe improve their quality of life. It’s heartening to hear of more and more companies reevaluating what it means to be “in business” and exploring new models.

I haven’t worked with inflatables such as this, but my concern would be weight. Given the thickness you would need to make something of this size puncture resistant, I would think that it might become too heavy to make remote distribution feasible.

Hi Mark,

Thanks for bringing Michelle’s story to life. I understand from some folks I’ve worked with that algea buildup can be a pretty tough problem with aqua systems. Their solution is to tarp all exposed areas, especially the fish tanks. If the tarp was strong enough, it could keep the dogs dry too!