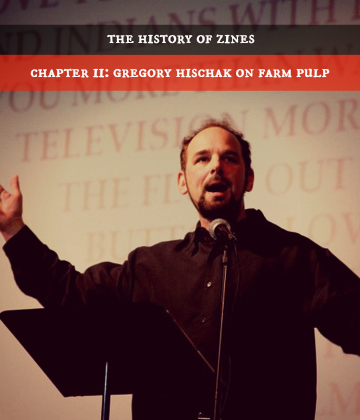

In an attempt to better document the American underground press, or at least the sharp tiny sliver of it that I find most interesting, I’ve given myself the task of reaching out to all of those former and current zine publishers that I know, and asking them about their motivations and experiences. Today’s interview is with the publisher of the juxtaposing little zine Farm Pulp, celebrated playwright Gregory Hischak.

MARK: As I don’t think I’ve ever seen the first issue of Farm Pulp, why don’t we start there… What can you tell us about it?

GREG: Some years ago I stumbled upon a pretty well-preserved copy of Farm Pulp Number 1 (I think January 1990) and, really, I couldn’t make heads or tails out of the thing. It was mostly a crude, vaguely punk juxtaposing of magazine headlines and random images. It was just all over the place… It was like looking at a little newborn surrealist cub rolling around, making a mess with sprayglue and tape.

MARK: By “vaguely punk,” do you mean strictly in an aesthetic sense, in that it looked like the cut-and-paste album art of, say, the Sex Pistols? Or was there, early on, a tangible tie to punk music? Was that the scene you came out of?

GREG: Its “Punk” lay in its aesthetic of cut and tape, and abrasive juxtaposing. Likely I was listening to Gang of Four, or thinking about them, while folding Farm Pulps. But Farm Pulp never really lived in, or popped out of, any one particular musical genre — pretty much like me.

MARK: Where did the name Farm Pulp come from?

MARK: Where did the name Farm Pulp come from?

GREG: The explanation of the name’s genesis takes longer than the actual genesis: I had a sheet of press type (this being the days when graphic designers were still called commercial artists too) and it was 30 point Caslon Open Face or something, and I had enough room across the top of the cover for nine characters. And, based on the letters that were left on the sheet (not many), FARM and PULP were the words I came up with, and I never saw any reason to change. In hindsight, I wish I had used ALARMPUP.

MARK: Was Farm Pulp the first thing you’d ever printed and shared with others, or were there earlier publications that I’m not aware of?

GREG: Well the first issue, the first half dozen, were pretty crappy, but it was pretty much what I’d always been up to. I made one-off constructions — small intimate assemblages to woo girls, or large room-sized installations that would get me invited to parties… Neither worked very successfully… But Farm Pulp was the first time I kind of codified the thing into mass-production, well at least dozens at a time, and then later in the hundreds.

MARK: Can you elaborate on these “small intimate assemblages to woo girls”? Are we talking painfully honest poetry over collaged battlefield photos… horribly cringeworthy stuff?

GREG: Well no one ever gave them back to me, so I’m not sure what they looked like now. Sometimes they were flat boxes that opened onto several layers of cut-outs. Sometimes they were long accordions, a series of z-folds that stretched several feet. Generally they were Surrealist, Dada things that dressed the real emotions in ambiguity. They were ambiguously honest and heartfelt, I suppose.

MARK: When did you first encounter Surrealism and Dada?

GREG: Sometimes I told my folks I was going to the library when in fact I was just going out to get stoned with my high school thug friends, but frequently I actually went to the library and I read the shelf of art books from left to right. So I learned about Dada early, and Surrealism much later on (shortly after Post-Impressionism and Renaissance, I suppose).

MARK: What was it about those two particular movements that resonated with you?

GREG: Well, in both movements the interpretation of any particular piece is tossed into the hands, and head, of the viewer. It’s a very collaborative relationship to view a piece of art that looks back at you and says, “Here is a hat and here is a tomato — make of me what you will.”

MARK: Do you recall the chain of events leading up to the publication of that first issue? Was there something that had inspired you? Had you perhaps seen a copy Factsheet Five?

MARK: Do you recall the chain of events leading up to the publication of that first issue? Was there something that had inspired you? Had you perhaps seen a copy Factsheet Five?

GREG: I’d moved out to Seattle and left a lot of people back in Ohio, and so I primarily made the magazine for them as a “Look I’m still alive and just as ridiculous” scrapbook/journal. From the very first issue the size was established and never varied (though the page count always did). I made it the same size as National Geographic (6.75” x 11″) so that I could print it off on 11” x 17” paper, which would accommodate fold-outs and gates and insertions of smaller sheets. I’m crazy about letting a page turn reveal an idea, or a joke. Like Mad Magazine’s back cover fold-ins and those sprawling revelations that National Geographic did to show you where Alexander the Great got Dysentery. I was up to issue 9 or 10 before I was shown a copy of Factsheet Five and I realized I’d inadvertently created something that was not only already created, but had its own culture and secret handshake. I was taken aback, and then I quickly became aware of FS5’s ability to get people to send me money.

MARK: How much money are we talking about? Nowadays you occasionally hear about bloggers striking it rich. I don’t remember that so much with blogs. I guess a few people got book deals, or guest spots on TV, but I don’t think most of us came close to breaking even. How did you do?

GREG: On my really flush weeks I got twenty bucks. Sometimes several weeks in a row like that and then nothing. Later on there was a sporadic zealot who wanted to buy every back issue. I worked at getting book deals. There were proposals pushed here and there, but I never felt the stuff would work as well when it hit that glossy paper, and editors generally agreed. Michael J. Rosen printed a bit of my Pulp material in his Mirth of a Nation anthologies. He’s a handy friend, and, through him, I’ve also designed a lot of other humorists books for different presses.

MARK: That’s funny. As I recall, several years ago – like well over a dozen years ago – I got contacted about Mirth of a Nation. Letters were exchanged, but, in the end, I guess I didn’t make the cut. I also went through the whole pre-interview process at This American Life, only to get the boot when they stumbled on a story about elderly shoplifters that fit that particular episode’s theme better than what I’d been asked to talk about. The zine somehow found its way into the hands of the right people, but, for whatever reason, I wasn’t ever able to take advantage of that fact… What’s the biggest door that Farm Pulp ever opened for you?

GREG: Well it didn’t open doors to any world stage, but it put me in the living rooms of writers in Seattle, and I was embraced as “the Farm Pulp editor,” and treated like a writer by writers. So I magically changed shape into that of a writer… That’s what Farm Pulp opened.

MARK: How did you distribute in the early days, before you learned the secret handshake and began pushing copies of Farm Pulp out through the zine underground? In addition to mailing them to friends back home, were you leaving them around Seattle for people to find? Or were you handing them out at parties?

GREG: I handed out a lot of copies in addition to hitting all the local independent bookstores — and Seattle had a lot, Portland had a lot too — Elliot Bay Books, Left Bank Books, Powell’s, Reading Frenzy — great stores run by great folks. I sent copies to bookstores in the bay area as well, to Atomic Books in Baltimore, See Hear in New York — they all took on copies. Later, I had distributors do the legwork, but they were always ineffective, sending issues off to chains, and a lot of those copies probably went into the trash.

GREG: I handed out a lot of copies in addition to hitting all the local independent bookstores — and Seattle had a lot, Portland had a lot too — Elliot Bay Books, Left Bank Books, Powell’s, Reading Frenzy — great stores run by great folks. I sent copies to bookstores in the bay area as well, to Atomic Books in Baltimore, See Hear in New York — they all took on copies. Later, I had distributors do the legwork, but they were always ineffective, sending issues off to chains, and a lot of those copies probably went into the trash.

The handing out of copies of Pulp reminds me of another on-going project during my time in Seattle: the circulation of brochures for Big Squirrel Lick National Park — a totally ficticious National Park. I made little tri-fold brochures and slipped them into tourist info kiosks all over Puget Sound. I like to think that at some point I had fleets of RVs moving back and forth across Idaho and Montana looking for a not-so-pristine fantasy destination. I like to think that lives were changed.

MARK: I don’t mean this in a bad way, but would you say that there’s a part of you that enjoys fucking with people?

GREG: There is fucking with people for the sake of fucking with people — which I don’t do, unless a telemarketer calls and I start jabbering in mock-Croatian until they hang up. And then then there’s jarring people into looking at something differently than they have before. Big Squirrel Lick is mostly about asking people exactly what is their relationship to physical landforms, and the history of these landforms — geologic, political, cultural… “Are you a voyeur, or a collector of giftshop trinkets, or are you so restlessly looking for something that you would start driving across very sprawling states based on a brochure you picked up?” With Farm Pulp I liked to set up expectations with the reader — that they were about to delve into an article, and then twist it, or a page suddenly unfolded to reveal a larger graphic agenda.

MARK: How old were you when you set out to work on that first issue, and what were you doing at the time?

GREG: I moved to Seattle from Cincinnati when I was around 29 years old. I was a graphic designer and continued being a graphic designer which meant I had a lot of unsupervised access to office machinery and, hence, a zine. I believe Farm Pulp put a lot of graphic design firms out of business, and, for that reason alone, it should be lauded.

MARK: What was it that motivated you to leave Ohio for Seattle?

GREG: I followed a woman to Seattle—I kind of had to because I was married to her and then I followed a woman to Cape Cod because I was married to her—not the same woman though. I suppose we should talk more about zines.

MARK: How many issues of Farm Pulp have you published? And how has it evolved since that first issue?

MARK: How many issues of Farm Pulp have you published? And how has it evolved since that first issue?

GREG: Farm Pulp ran about 12 years and made it to Issue 42 which was entitled Colophon, which is Greek for “finishing touch” and refers to an acknowlwdgement of fonts used in a book’s production. By Number 10, one of the first that got widely reviewed, it had a much more controlled layout and I’d learned what worked coming off particular copiers. By Issue 12 the found text had been replaced with my own writing, and the occasional guest contributor (like you — the check is still in the mail). It became, with each issue, a little cleaner and more thematically focused, and really it ceased being about culture at large which is what a zine was supposed to do, and became a strange meditation on whatever interested me at that time. Each issue would have 6 or 8 stories centered around — stuff. One issue would be insects, another was James Thurber, the End of the World, Maps, Staplers, Childhood… I could name all 42 if you like.

MARK: Was it a difficult transition to make, actually using your own writing instead of found text?

GREG: It was surprisingly easy and I don’t know why. It definitely complicated and yet simplified the development to take on all that writing. The benefit was that suddenly I had control over the tone and voice, which you couldn’t get with found text. And, because I never saw it as going to a wide audience, I felt no intimidation whatsoever in what I typed. The drawback was that I had no intimidation whatsoever in what I typed.

MARK: Is Farm Pulp now officially dead, or might we see it come back in some way?

GREG: The logistics of paper and postage and folding time (I spent a lot of the 90s folding paper) means that Farm Pulp will never surface in the print medium. If I inherit a copyshop that could change – are there even copyshops anymore? Really, the writing still exists and it’s constantly being produced, and the imagery is contained neatly in the writing.

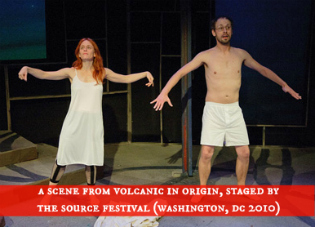

Farm Pulp was being produced concurrently with my being a slam poet and performing and traveling a lot in that capacity. And both evolved together into writing for the stage. Theatre work became much more intriguing and there were more rewards that came with that. The primary reward being that a LOT of people got exposed to the work as opposed to a trickle of packages sent through the mail.

MARK: On the other side of the equation, though, your written work stays in circulation, whereas your plays, once they’re performed, are lost to the ether, right? I mean you have that big audience for a few days, but, unless someone chooses to mount a new production, it kind of fades away… Or, I suppose, you could publish the plays in some way, or rework them for film…

GREG: That’s true, it’s pretty much a visceral thrill of limited duration. Several of my short plays get published, though. And the Humana Festival Anthology and the Smith & Kraus anthologies seem to make their way to schools and universities. And my play Hygiene has had four productions in the last 12 months. I haven’t seen any of them, but I’m hoping that somebody did.

MARK: Do you direct as well? And, if not, is that difficult… handing your baby off to someone else to raise?

MARK: Do you direct as well? And, if not, is that difficult… handing your baby off to someone else to raise?

GREG: I don’t direct much at this point except during the reading of a script in development. I trust the collaborative nature of creating theatre… I have a specific role and then others: directors, designers and actors have their roles. When it goes well it creates a work bigger than what you started with. When it goes bad it’s usually because my script left wires out that someone tripped over. Or sometimes the director didn’t ask the right questions or I forgot to say the basics, like “It’s about dogs, not impressionists.” Usually the collaboration is a joy.

MARK: You mentioned having left Cincinnati for Seattle. If I’m not mistaken, though, you grew up in Dayton, right? What was childhood like for you?

GREG: These are all true things, and, had I a more well-adjusted childhood, I wouldn’t have had to resort to photocopiers to get people’s attention. That said, at least it was positive attention. I had an early childhood in Upstate New York before shipping out to Dayton with my family — I had no choice in the matter, I was six. In Dayton I once successfully stopped three hoods from beating me up by making them laugh. That’s where I decided comedy was my forte. I also became a hood for a while, which was nice too. Dayton is the Birthplace of Aviation, you know.

MARK: Do you remember the joke that made the guys stop beating you up? I can foresee a scenario where it might come in handy for me someday.

MARK: Do you remember the joke that made the guys stop beating you up? I can foresee a scenario where it might come in handy for me someday.

GREG: Yes, I completely lifted it from Woody Allen. As both of my arms were pinned behind my back I told them (four of them) I was going to write an angry letter to the Times. They cracked up.

MARK: When did play-writing come into your life? Were you writing for the stage since the very beginning of Farm Pulp, or did that come later?

GREG: My upbringing was pretty rife with theatre and broadway cast albums, and I was raised to see playwriting as a kind of normal thing that people did, in addition to having day jobs. The stage writing kept pace simultaneously with Farm Pulp’s development. My first (lousy) full length play was written for the Seattle Fringe Festival in 1994. There were two wonderful staged revues of Farm Pulp work produced by A Theatre Under the Influence (in Seattle). The Wright Bros material I used in Farm Pulp #41 (Birthplace of Aviation) turned into a performance at ACT in Seattle and then underwent development and grew into a very solid play. The premier of its final incarnation was with Portland Stage Company (Maine) in 2011, and it’s again in production for a Spring 2014 run here on Cape Cod at the Cotuit Center for the Arts. A crazy piece from the Thorax, Abdomine & Nematodes issue (#29) turned into a very nifty short play that made it to the Humana Festival of New American Works… I only bring all this up to show that Farm Pulp still lives and breathes, but it does so behind smarter looking clothing.

MARK: You mention growing up in an environment where playwriting was a kind of normal thing that people did in their spare time, after work. Was one of your parents a playwright?

GREG: My parents were not particularly creative sorts, but they were indulgent enough. My oldest brother (Thomas S. Hischak) was already putting plays together in basements when I was a tot. He continues to put on plays and writes extensively about people who put on plays. I cannot tell you the number of books covering theatre and film that he has published, but they would fill up a bookshelf.

MARK: How would you characterize your relationship with you brother? Are you competitive? Would I be over-thinking things if I were to suggest that, in some small way, especially at the beginning, you might have been seeking his approval?

GREG: No, not so much competitive as mentoring, I suppose. My brother is nine years older than me so we were never hung side by side for comparisons. Also, my brother and I tackle different aspects of theatre. Tom has a grasp of the history and the voices starting with the Greeks… He knows the American songbook and it’s history as well… With me, I’m always sneaking into theatre through an unsecured door. I’m always going to be more of a fringe element, and so we never really see each other as competitive.

GREG: No, not so much competitive as mentoring, I suppose. My brother is nine years older than me so we were never hung side by side for comparisons. Also, my brother and I tackle different aspects of theatre. Tom has a grasp of the history and the voices starting with the Greeks… He knows the American songbook and it’s history as well… With me, I’m always sneaking into theatre through an unsecured door. I’m always going to be more of a fringe element, and so we never really see each other as competitive.

MARK: You’re aware that Farm Pulp number one says “sibling rivalry” right on the cover, right?

GREG: That’s right. And by “sibling rivalry” it should be understood to mean: “absolutely no sibling rivalry.” Never underestimate the distinctly human trait of contradiction.

MARK: Do you miss having Farm Pulp around to test out these concepts?

GREG: I do. It was a very handy publicly-shared notebook of ideas.

MARK: I’m not incredibly well versed in theater, but I’d like to think that, if forced to (by four young men holding my arms behind my back), I could hear a few lines and tell, based on the subject matter, the delivery and the phrasing, whether they were written by Samuel Beckett, Bertolt Brecht, or David Mamet. Having never seen your work performed, however, it would be difficult for me to identify “a Gregory Hischak.” Is there a recognizable palette that you work from that would distinguish your work from that of others?

GREG: My theatre voice is pretty recognizable even before the subject matter gives the authorship away. I write pretty rhythmically… Rythmicality I guess is the phrase… The dialogue is frequently quick and overlapping, you can tap your foot to it and that allows the breaks and stops to really carry some resonance.

MARK: How about subject matter? What do you tend to write about when writing for the stage?

MARK: How about subject matter? What do you tend to write about when writing for the stage?

GREG: I don’t have a pat formula for that and I make a lot of false starts based on what I think might work. I think of actors and what they would like to do, and I think of what would I like to do to an audience, and what an audience will want to talk about after seeing a piece. Sometimes I imagine a scenario where two audience members face each other over drinks after seeing my play and one says, “I don’t think I can ever look at a red dress the same again.” That begins my writing a play about a red dress.

MARK: So you write primarily about women’s clothing?

GREG: No, I haven’t yet, but the idea has been planted.

MARK: What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever received?

GREG: My friend James who was acting in Big Geology Cabaret took me aside to inform me that three times was always funny but four times was overkill.

MARK: What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever given?

GREG: That three times is funny and four times is overkill, but five times becomes funny again, and six times slays… Actually, I try not to give too much advice.

MARK: So, what are you up to these days? Are you still living on Cape Cod, where my family and I tracked you down several years ago?

MARK: So, what are you up to these days? Are you still living on Cape Cod, where my family and I tracked you down several years ago?

GREG: I do live on Cape Cod, which is primarily a long spit of sand jutting out into the Atlantic where retired people congregate to eat steaktips and flounder. However, when those people go to bed, there’s an amazing arts community flourishing and they’ve been a great support and they make me feel like I am home. I write a lot but I never write enough and I facilitate a lot of poetry events and classes — high school workshops, Cape Cod Writers Center. Scripts always get started and occasionally completed. I’ve endeavored to step away from graphic design and work within an arts organization. To this end I’ve somehow found myself the Associate Director at the Edward Gorey House here in Yarmouth Port. I have a daughter and Edward Gorey to shepherd through this complex world. Edward has of course already passed away so there is a limit to the damage I can do to him. It remains to be seen about my daughter…

MARK: What can you tell us about Gorey that we might not already know?

GREG: That he was a decent cook and attended every single performance of the New York City Ballet from 1959 to 1968 — or thereabouts.

MARK: What did he think of Charles Addams? Is there any evidence of nasty notes having been passed back and forth?

GREG: Addams’ prime work was a bit before Gorey’s time, but they might have passed each other once in the hallway of the New Yorker. Gorey wasn’t influenced by many cartoonists, but a lot of cartoonists and comics embraced his sense of the absurd. His actual influences were all over the place, but it’s safe to say that there were large cuts of Lewis Carroll, Edward Lear and Agatha Cristie marinating in Rene Magritte and Max Ernst.

MARK: Do you actually live in Gorey House? Do you make toast using his toaster?

MARK: Do you actually live in Gorey House? Do you make toast using his toaster?

GREG: His house in Yarmouth Port is called The Elephant House for a couple conflicting reasons and I don’t live in it (at this time), though his toaster is there and the kitchen counter is still covered with his rock collection and there’s something in the back of the fridge that might be his.

MARK: Gorey, if I’m not mistaken, referred to himself as “sexless.” Is there a sexlessness in the air?

GREG: No, it’s a very sensual place and kind of a rambling affair. Originally built by some sea captain back in the day. At some point someone planted a southern magnolia — a tree that won’t usually grow up in New England, but, because it was sheltered by the house on the north and west sides, it thrived, and now rather shelters the house. When Gorey was alive, the place was crammed with his books and sculpture and puppets and Golden Girls video cassettes and cats. Not sexy but sensual in that eclectic way, a curiosity about everything… Well, everything except sex, I guess.

MARK: Have you made any significant discoveries on his property? Have you, for instance, stumbled on an old trash pit that might shed some light on his favorite liquor, or brand of mayonnaise?

GREG: His video cassette collection is still lying around in boxes — Petticoat Junction, Xena, and such.

MARK: Well, the discovery of Petticoat Junction tapes should put to rest any talk of him being sexless once and for all… those beautiful young women swimming naked in their town’s municipal water supply.

GREG: They probably hold up surprisingly well.

GREG: They probably hold up surprisingly well.

MARK: I haven’t spent a lot of time analyzing why it is that I think I got into zines. I suspect, however, that insecurity probably played a significant role. I liked the fact that I could send out issues of Crimewave and get back letters from around the world, from people who genuinely liked what I’d put out there. I think I wanted approval. And, being too shy to just walk outside and make friends like a normal person, I sought to do it through the magazine. And I imagine that’s true for a number of us. Have you considered why it is that you invested so much time and energy?

GREG: Well if you just change the name Crimewave above to Farm Pulp you’ve told my story and I apologize for making anyone read this far because, really, that’s it in a nutshell.

MARK: I wonder what percentage of creative work is driven by insecurity…

GREG: An actual number? I think 72%. If insecurity covers the angst of where you fit into society, which part of it will you breed in, or not breed in, and what people will say of you when you’re gone or your back is turned.

MARK: At some point, you started creating sheets of stamps, and including them with Farm Pulp. How did that come about?

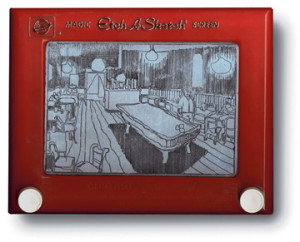

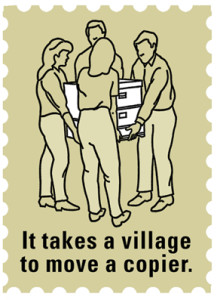

GREG: Until I discovered that Factsheet Five was mapping a whole culture called “zines” I considered Farm Pulp to be an art book, and Seattle was choke-full of artist stamp makers — an odd community that includes visual artists, poets, performers, hobos and civil war re-enactors. Eventually I gravitated toward the zine community because, well, I was making a zine but I liked stamp making. It all was a hold-over from dadaism and then later the fluxus movement in the early 60s (performance-oriented gallery events by folks like Yoko Ono and John Cage and others). Stamps were just one of the mediums, actually everything was a medium. With stamps you documented un-documentable things and that made them not just commemorative but commemorable. I commemorated office supplies a lot because someone needed to. I used Etch-A-Sketch a lot to record events. Then I commemorated Etch-A-Sketch in stamps. Had I broke my leg skateboarding I would have made a sheet of stamps commemorating that. Fortunately I didn’t… Actually, I’ve never skateboarded in my life.

GREG: Until I discovered that Factsheet Five was mapping a whole culture called “zines” I considered Farm Pulp to be an art book, and Seattle was choke-full of artist stamp makers — an odd community that includes visual artists, poets, performers, hobos and civil war re-enactors. Eventually I gravitated toward the zine community because, well, I was making a zine but I liked stamp making. It all was a hold-over from dadaism and then later the fluxus movement in the early 60s (performance-oriented gallery events by folks like Yoko Ono and John Cage and others). Stamps were just one of the mediums, actually everything was a medium. With stamps you documented un-documentable things and that made them not just commemorative but commemorable. I commemorated office supplies a lot because someone needed to. I used Etch-A-Sketch a lot to record events. Then I commemorated Etch-A-Sketch in stamps. Had I broke my leg skateboarding I would have made a sheet of stamps commemorating that. Fortunately I didn’t… Actually, I’ve never skateboarded in my life.

MARK: What’s the best thing to ever come from Farm Pulp?

GREG: There was an incredible amount of effort put into those 42 issues but it was rarely a chore. Even all that folding was a zen-like meditation and while I knew that it was unlikely to lead to greatness the community that it was part of made me feel like I was part of a movement — a member of that great horde of individuals who were defining the decade, and I guess we did a good job of it. It was a good decade and we celebrated it with a lot of paper. I’m happy that the body of work I did, all that dark stupid loam now rotting quietly in boxes and archives, allowed a lot of other work to grow and flourish.

MARK: Let’s say, hypothetically, someone stumbles across this interview and is intrigued to the point where he or she desperately wants to experience Farm Pulp firsthand. Might you be persuaded to slide a shovel under that pile of loam and put a bit in an envelope?

GREG: Yes, have their people call my people. We’ll haggle.

MARK: What are your current obsessions?

GREG: I am still struggling with the Big Squirrel Lick National Park script—in fact, I’m answering all these questions at length just to avoid getting to work on that. After that there is a play about Eugene Baskerville, the typesetter and Mrs. Eaves, his second wife. I also can’t stop humming through the Burt Bacharach/Hal David song catalog. I’m thinking of seeing a specialist in Boston.

MARK: If some day, a talented young man in Yarmouth were to find himself caretaker of the Gregory Hischak House, what would you like for him to know about you?

MARK: If some day, a talented young man in Yarmouth were to find himself caretaker of the Gregory Hischak House, what would you like for him to know about you?

GREG: I love that question and will answer it this half-assed way: there are no secrets to discover here but keep the place swept and the gift shop competitively priced. I have always surrounded myself with found objects — actually objects that have found me. Usually they fit in my hand but sometimes they veer me off in decade-long tangents. At the Gregory Hischak House (closed Mondays) there will be a docent who shows people around saying things like, “He seemed a bit directionless but he was loved and he was very lucky.”

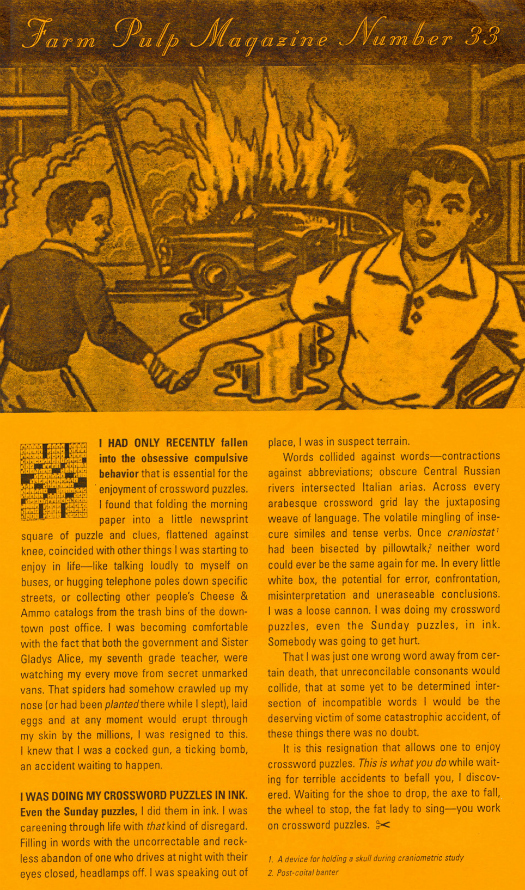

UPDATE: Here, for those of you sorry sons-of-bitches who have never seen a copy of Farm Pulp, is a bit of detail from issue number 33. The layout, including folds, can be found here.

[EXTRA SPECIAL BONUS FOR THOSE WHO ACT WITHIN THE NEXT FIVE MINUTES: A rare scan from Farm Pulp 37.]

[If you like what you’ve read above and want more, be sure to check the other interviews in the History of Zines series.]

15 Comments

Greg, to my knowledge, was not responsible for this.

Someone needs to make a brochure for the Gregory Hischak House.

They wanted to call it something other than Farm Hussy, but those were all the letters that were left.

This delightful interview left me wondering one thing. Is Big Bone Lick National Park real? I drive by the sign all of the time but I’ve never exited the highway to look for it. Might it be the work of pranksters like Mr. Hischak who erected a sign in the middle of the night?

It’s great to hear that the old school guys like Greg are still stirring shit up and challenging people. Who else is on your list? Will you be speaking with Doug Holland of Pathetic Life fame?

I’d be hard pressed to determine the sexuality of a man who found pleasure Xena, Golden Girls and Petticoat Junction. If I had to, I’d say omnisexual.

I’ve heard that gay men like the Golden Girls, but the only person I ever knew to watch it was a sexless middle aged man. He also watched Hart to Hart and listened to Prairie Home Companion. As for Xena, I hear it’s big with lesbians. It sounds like Gorey had a lot going on.

As for Doug Holland, he’s definitely on the list of people I’d like to interview for this project. I’ve heard, however, that he’s unreachable these days. We’ll see.

Big Bone Lick is a State Park and in, I think, Kentucky and not far from French Lick which is in Indiana. A Lick is a salt vein, an ancient seabed remnant — but you guys knew that.

“To woo girls.” I note that your motivation, Greg, was anticipated carnal delight, your desired life goal a mere footnote (“2. Post-coital banter”, Farm Pulp Magazine Number 33, cover).

I shudder to think, had you suffered a later birth in an era of effortless eharmony dating, your passion would have skidded to a halt in the Birthplace of Aviation. Satiated, you’d still be living in a suburb on the flight approach to the airbase, near a (once) thriving factory town.

And writing canned script for the local cable monopoly support desk. “Unplug the power cord. (You have to unplug it, not simply turn the power off.) Leave it unplugged for a minute or two, then plug it back in and turn on…”

That’s not a terrible thing, I suppose. Who can forget the back cover of Dayton, Ohio’s 1973 yellow pages? No doubt written by a successful swordsman, the tri-state map was emblazoned “The nation’s third largest 90-minute market, in reach of almost One Million potential clients!” Unforgettable.

I spent the entire day cleaning house. Among other things, I found a ’91 copy of Factsheet Five, which contained the following Farm Pulp review.

And, for what it’s worth, I’m considering writing a play called Farm Hussy about the adventures of a door-to-door zine salesman in the 1920s.

So great to come across this article…I’ve been scouring the internet for back issues of Farm Pulp for years and so far have about four issues…I think that well’s run dry, unfortunately.

One thing I always wondered: would Greg paste up all the imagery and then write around that, or vice versa? The text and imagery are so intertwined it’s hard to imagine the writing being done first.

Nice to see this history surface. I think I might be the ‘sporadic zealot.’ They’re all comfortably nestled in a box in my apartment, with their mid-90s companions of other provenance.

Appreciatively,

Brenda

San Francisco

Interesting. I missed this post. I am intrigued by the literary work that is “Farm Hussy.”

Don’t those people have better things to do than worry about a busy milk maid?

Just toured the Gorey House last Sunday, hosted by Gregory Hischak. He was the perfect tour guide and his energy and erudition suggested there were multitudes within. A quick Google led me to this exquisite corpse of an interview. And Mr. Hischak proves as fascinating a polymath as I suspected. What a treat! Thank you.

3 Trackbacks

[…] of course. Pathetic Life, The Scaredy Cat Stalker, The Inner Swine, Crank, Beer Frame, Stupor, Farm Pulp. All sorts of great stuff would show up in my mailbox. I remember reading something you wrote, […]

[…] Not too long ago, I was interviewing Greg Hischak about the evolution of his zine Farm Pulp, and, when I asked him about making the transition from found text to his own writing, he said that […]

[…] In talking with Greg Hischak about the start of Farm Pulp, he said that he only discovered Factscheet Five after having produced about 9 or 10 issues. “I […]