OK, as long as we’re talking about David Avery’s service during the Revolutionary War military under Colonel William Prescott, I should probably mention that he wasn’t the only one of my ancestors to fight against the British. His son, Daniel Avery, fought them again in the War of 1812, and, ultimately, that’s what brought this branch of my family to the midwest.

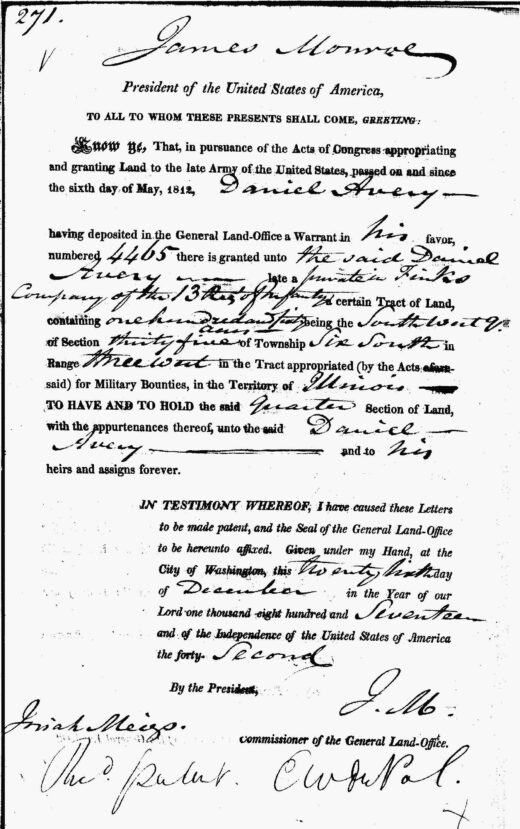

You see, on May 6, 1812, the United States legislature passed an act of Congress which set aside so-called bounty lands as payment to volunteer soldiers who fought in the War against the British, or, as we now refer to it, the War of 1812. And, on December 26, 1817, Daniel Avery was given 160 acres in the area of Schuyler, Illinois, just west of the Illinois River. [The law passed in 1812, but it took until 1816 for all of the land to be surveyed and opened to settlement.] I don’t know whether Daniel Avery made the choice to take land in Illinois, or whether or not it was just assigned to him, but that’s where the family went, and where they stayed for well over 100 years. [Land in both Arkansas and Michigan was also being offered up through this program, which made approximately 3.5 million acres of land deemed fit for cultivation available for military bounties.] Here, if you’d like to see it, is the document that brought the Averys west to Illinois. [A higher-resolution image can be found here.]

If not for this piece of paper, Daniel Avery would likely never have come to Illinois, and over 100 years later, my grandfather, Robert Avery, would never have met his wife, Dorothy Lambie, and my mother never would have been born… So, thank you, President James Monroe, for my existence. If not for you, I would not be here today.

As for my great, great, great, great, great grandfather’s service during in the War of 1812, all I know is what’s on this paper… namely that he served as a Private in the 13th Infantry, in a company under the command of Captain John L. Fink, which was headquartered at Sackets Harbor, New York. [I haven’t looked at them yet, but, as luck would have it, Captain Fink’s papers at the University of Michigan’s Clements Library.]

And, yes, it would appear as though my ancestor, abetted by the United States government, took possession of land that had been home to Native Americans for centuries. The white population of Illinois, according to Wikipedia, “exploded after the War of 1812, exceeding 50,000 in 1820, and 150,000 in 1830.” And, as a result, U.S. government liaison Thomas Forsyth, in 1828, informed these native Indian tribes that they should begin vacating their settlements east of the Mississippi, setting the stage for the Black Hawk War of 1832, which, as we know, the United States won. So my very existence is not just predicated on the above letter, granting my great, great, great, great, great grandfather land in the Illinois territory, but on the forced relocation (and systematic genocide) of the Sauk and Meskwaki (Fox) people who lived along the Mississippi River… something I will be discussing with my children this evening over dinner.

10 Comments

Quite a few people who got these land tracks never went. They sold them to speculators. As I enjoy your blog, I’m glad your family went.

I know that everyone who came here post-Columbus is guilty of taking Native American land. It’s part of the deal when you start researching your family history if you’re a white American. You know there’s going to be bad stuff. You know, if you had ancestors here early on in the American experiment, that they, either directly or indirectly, fucked over the people who predated them on the continent. And I was prepared for that when I started digging through the archives. I wasn’t expecting, however, that my ancestors would be among the first people pushing west during the post-War of 1812 expansion. I guess I thought that they moved out later, once a little more time had passed. I mean, I thought that I’d be thinking about these issues with earlier ancestors, some of whom may have been in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, but I didn’t think it would come up with the Averys of Illinois. And now I’m reading about the forced relocation of the Sauk and Fox people, who, beginning in 1825, were pushed to Iowa, and then Kansas, and wondering about the role my ancestors played. [Apparently that was also after years of pressure from the French had pushed them into Illinois.]

So, yeah, I’m sitting here tonight trying to reconcile these two things. First, I wouldn’t be here if my great, great, great, great, great grandfather hadn’t moved his family to Illinois after the War of 1812. And, second, that my family played a part in a system that saw the Sauk and Fox tribes absolutely decimated. I suppose I could try to downplay the role of my ancestors, and say it was a different time, and that these actions were made possible by treaties, and that other people were the ones who ultimately made the decisions, but, with over 200 years of hindsight, it’s difficult not to see the criminality of it all, and the cruelty of the system that was put in place by the European occupiers.

I don’t know how accurate it is, but here’s a brief history of the movements of the tribes…

But isn’t this always the case in human history? Tribe A takes lands previously considered as territory of tribe B, who might have taken it from tribe C. Since tribe A is the latest tribe to occupy the land, the story is told from the view of tribe A, with only a few remembering the story of tribe B, and none remembering tribe C, since it was so long ago. The difference now is that more people in tribe A are interested in the story of tribe B and tribe C, with the goal of moving beyond tribe A. B, or C to form a supertribe ABC. You shouldn’t feel bad about that. I don;t even know if we can be a supertribe, but it’s a noble goal to strive for. Regardless, supertribe ABC will be the name of my new band.

I think Anonymous’ post makes more sense in this thread.

Anonymous

Posted January 3, 2020 at 9:11 am | Permalink

I had a roof leak once. I got out the ladder and then decided it was too difficult to tackle on my own. Since I had already picked up the hammer, I decided to fix the plumbing in the basement. It was a shame to let such a fine tool go unused.

I don’t get it. What’s the hammer, what is the leak, and what is the metaphorical plumbing in this story? Where is the roof, what does the basement represent, and who is the plumber?

I don’t get it. What’s the hammer, what is the leak, and what is the metaphorical plumbing in this story? Where is the roof, what does the basement represent, and who is the plumber?

I’m sure there are genuine Lucky Pierres out there who can teach you how to receive the metaphor.

My son at 10, after a discussion of tribalism and war along the lines of Anonyous’ ABC:

“Mom you know what would end all tribalism and tribal conflict on earth?– Aliens.”

Why this sudden bewilderment, this confusion?

(How serious people’s faces have become.)

Why are the streets and squares emptying so rapidly,

everyone going home lost in thought?

Because night has fallen and the barbarians haven’t come.

And some of our men just in from the border say

there are no barbarians any longer.

Now what’s going to happen to us without barbarians?

Those people were a kind of solution. — CP Cavafy (written in 1898 and still apt)

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/51294/waiting-for-the-barbarians

Seriously, does anyone understand what Foolish Fakes is talking about?

I wonder if this guys roof and plumbing is in good working order?

Rosneft

https://youtu.be/FSj-BCOlGPY?list=PLZbXA4lyCtqqWt3kGPEFd8dICNnmqqfzT

2 Trackbacks

[…] you may recall, it was a land bounty earned by my ancestor David Avery after his service in the War of 1812 that bro…, so I’d thought that something similar may have happened here. There were, after all, bounty […]

[…] great great, great grandfather hadn’t fought in the War of 1812, earning a land bounty that brought the family west to Illinois, where my grandfather would eventually meet my grandmother some 120 years later, I likely […]