Over the past several weeks, it’s come to light that Water Street, the 38-acre parcel of downtown, riverfront property that the City of Ypsilanti has been trying to develop for the past 16 years, may be significantly more toxic than we’d previously been led to believe. What follows is the first of what I’m hoping will be several conversations with Ypsilanti’s Director of Economic Development Beth Ernat about the toxicity of Water Street, how it is that we’re just now coming to know how bad it really is, and where we go from here. Hopefully this first discussion of ours will both help dispel some misconceptions that are out there about the situation as it stands today, and shed some light on how it is that, after 16 years, we still don’t know the full extent of the damage done by the businesses that had been active on the site… Happy Earth Day!

[The image above shows the Water Street Commons native plant prairie, which was shut down by the City a few days ago, shorty after they closed down the portion of the border-to-border trail that runs through Water Street.]

MARK: Let’s start at the very beginning… Since the mid-1800s, the 38-acre collection of parcels we now know collectively as “Water Street” has been home to numerous small companies, some of which were working in relatively dirty industries. The property has seen print shops, manufacturing companies, and foundries, among other things, spread across its 40-some individual parcels.

BETH: This is true. To my knowledge, there was also a landfill, a mill shop, and several auto repair shops. And, we should note, there were very few environmental regulations in existence prior to the 1970s.

MARK: And those regulations that were passed in the ‘70s have continued to evolve over time.

BETH: Right. The regulations continue to change and evolve as more information becomes available about chemicals, products, and the effects they have on those who come in contact with them. The governing legislation as relates to residential contact is called the Toxic Control Substances Act of 1976 (TSCA).

MARK: And a lot of these companies that existed on Water Street, as we know now, left behind chemicals that are known to be harmful, like PCBs.

BETH: Yes. Old oil and fuel products tend to leave behind the most contamination… PCBs are a byproduct of oil when it’s used in the operation of equipment, vehicles and buildings. And, as such, PCBs are the most widespread and common toxic substance found on Water Street today. There are also, however, concentrations of lead, VOCs, and chemicals such as arsenic.

MARK: OK, let’s step back for a minute, before we start going too deep into the contamination, and discuss how the City came to be in possession of Water Street… It’s my understanding that, in late 1990s, Cheryl Farmer, who was Mayor at the time, and members of the Ypsilanti City Council, decided that it would be in the City’s best interest to reimagine these 38-acres of downtown riverfront property. As I understand it, this was seen as an opportunity not only to push older, dirtier industry from the City, but to open up a significant piece of riverfront real estate to new development, which would in turn raise tax revenues, allowing the City to maintain services, etc.

Had it worked, I suspect we’d now look very favorably on the decision. It didn’t, though… After going into significant debt to acquire all of the individual properties, and create this unified 38-acre parcel, Biltmore, the company that we’d brought on as a partner to build higher-end townhouses across the entire site, and construct retail spaces along Michigan Avenue, backed out, leaving us with no plan and millions of dollars in debt.

BETH: Yes, but it’s worth noting that, regardless of whether or not the City had purchased the property 16 years ago, we’d still likely be in much the same position today relative to contamination. As you previously stated, the uses on the property were largely industrial in nature and were causing environmental damage. It’s also worth noting that most of these industries didn’t survive through the late ‘90s and early 2000s. In other words, it’s doubtful that they’d still be in operation today, and investing in the necessary remediation themselves.

MARK: Agreed. Leaving aside for the moment whether or not it was wise for the City to get involved in real estate speculation, had these polluting companies stayed on Water Street, we’d likely have more toxins to contend with now.

BETH: Right. The contamination would still be present on the site today and redevelopment would be still be limited… I was not an Ypsigander at the time, but I can appreciate the conundrum from a redevelopment perspective. It’s long been considered good practice for municipalities to acquire and bundle properties for redevelopment. Yes, this site had challenges, but these challenges would have been much worse had multiple private owners been involved. Also, because the City owns the property, we were able to create a Brownfield TIF to help finance redevelopment-related activities.

On a smaller scale, we’re dealing with the same thing at 2 West Forest, the former Farm Bureau site. Although we don’t yet know the full situation relative to contamination, we know there are environmental challenges. It’s a prime site, but the costs associated with remediation are going to make redevelopment prohibitive.

MARK: I’m not terribly familiar with the 2 West Forest site. I believe, however, the building sold at auction sometime last year to an individual who claimed to have plans of some sort. Are you saying that because a private owner has possession of a brownfield property it’s going to make cleanup more difficult?

BETH: Yes, the property was purchased by an individual. We’ve only had one meeting so far, but the new owner has told us that he has a 5-to-10 year plan to transform the property. As far as we know, he’s not yet had any environmental studies done on site, though. This isn’t to say that development can’t happen. It can. I’m just making the point that it will be costly, and it will require expensive clean-up activity, which can be easier with public ownership. But we will work with any owner to make development happen.

MARK: OK, back to the history of Water Street, what else can you tell us about the acquisition and the remediation work that’s been done to date?

BETH: From my understanding, the City spent approximately $11 million in general revenue bonds on property acquisition, environmental assessment and a small amount of remediation. Additionally, the City has spent approximately $9 million of grant funds; $3.3 in Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) funds, $4.5 in Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) grants, and $1.75 in Neighborhood Stabilization Program (NSP) funds. [NSP is a federal grant program intended to stabilize communities hardest hit by the recession.] And there may be more that I’ve yet to uncover. Furthermore, the City has spent over $1 million in general funds on general upkeep, maintenance, and engineering not covered by grants over the past 16 years.

MARK: And the debt associated with the purchase has continued to grow over the last 16 years, even with the efforts of City employees to renegotiate, etc… As of right now, how much do we owe on Water Street?

BETH: The total debt for Water Street based on the original bond issue was $29,434,535. The City was able to recall the bond debt this year and refinance it, though. Based on current interest rates, a pay-down out of City savings, and a grant for over $3 million, as of May 1st, the remaining debt will be $11,140,000. The annual City payment will be $1,375,340 and will allow the City to pay-off the debt in 14 years. And, if the 2.3 mill levy is approved by voters in August, it would reduce that annual general fund payment to $924,500.

MARK: So, getting back to the contamination, would I be right to assume that, early on in this initial push to redevelop the property, both the City and Biltmore had environmental assessments of the entire parcel done, identifying areas of concern, etc?

BETH: Yes, both the City and Biltmore had assessments done. When commercial or industrial property is purchased, the purchaser is required to submit what is called a Baseline Environmental Assessment (BEA) in order to document the known contamination and restrict the purchaser’s liability by identifying what currently exists on the site. The City had BEAs done for each property it purchased. The BEA includes a Phase I, and sometimes a Phase II, environmental assessment. From the records I have seen, Biltmore started preparing some of this information as well, as they intended to be the purchaser of the property. Biltmore had also prepared a Document of Due Care and Compliance (DDCC) plan for the development of the site. When remediating contamination, a DDCC is required to be submitted to the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) as a guide to limit exposure to contaminants and to safely either dispose of them, or cap them.

[The above map, taken from the City’s 2014 Brownfield Plan for Water Street, shows the areas of concern as they were thought to exist until recently. The legend can be seen below.]

MARK: You mentioned Phase I and Phase II environmental assessments. What’s the distinction between the two, and are there other levels beyond them?

MARK: You mentioned Phase I and Phase II environmental assessments. What’s the distinction between the two, and are there other levels beyond them?

BETH: A Phase I Environmental Assessment is basically a historical research study of documents, owners, and uses of property. This provides an estimation of what environmental concerns may be present. A Phase II Environmental Assessment is a follow-up study with soil borings and lab analysis. A Phase II study is the most detailed assessment used, and can include many studies. Documents of Due Care and Compliance (DDCC) are created based on the Phase II findings. A DDCC is a written document that spells out how, step by step, a site is to be properly remediated in such a way that both protects the site site itself, and the adjoining sites during construction.

MARK: OK, so the city had BEAs done for each individual parcel they purchased 16 years ago. Some involved Phase I assessments, and some involved Phase II assessments. And then Biltmore either started or completed a BEA for the entire site before backing away from the deal. Is that correct?

BETH: Correct. Biltmore completed several Phase II assessments and a DDCC draft. The City purchased this documentation from Biltmore when the deal dissolved.

MARK: And, I would assume, a number of tests have been run on the site since that point, given that we’ve attracted state and federal funds to remediate distinct areas since Biltmore walked away, correct?

BETH: The grants acquired for remediation activity required that Phase I and II reports be provided as a starting point for remediation activity. Where studies were lacking, the grant paid for new assessments. And, based on what I’ve been able to find, quite a bit of that grant money for remediation was actually spent on assessment, as there was still a lot that we didn’t know.

MARK: It can’t be easy inheriting a project like this… I mean, there’s a ton of data, and, given the turnover in the City Manager’s office over the past 20 years, there can’t be much in the way of institutional knowledge as to what was done and why.

BETH: It’s definitely a complicated site, and it’s made more complicated by the fact that multiple environmental consultants have worked on the site over the years. And this is compounded by the fact that many of the files are incomplete. Furthermore, as there weren’t surveyor benchmarks on the site, we’ve never accurately marked the locations of testing and remediation. Additionally… and this is a big issue… the environmental standards have changed since some of this work was completed. For example, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) set the allowable residential exposure rate to PCBs at less than 4,000 Parts Per Billion (PPB) in 1995. Since then, though, the MDEQ has deferred to the EPA standard, which is less than 1,000 PPB.

MARK: So parcels that would have graded out as OK for residential development 20 years ago, now might not…

BETH: That’s true. Some things which didn’t require remediation activity in the past now do.

MARK: You mentioned just a moment ago that the site doesn’t have surveyor benchmarks. I suspect there’s a really obvious answer, but, without benchmarks, how did the City perform environmental studies of the individual Water Street parcels as they were being purchased? I mean, how do you determine how dirty a parcel is, if you can’t identify the parameters?

BETH: The site now has benchmarks, and, as of six months ago, everything can be identified by GPS coordinates. Prior to benchmarks, though, surveyors used things like the centerlines of streets, the edges of buildings, and other physical landmarks.

MARK: Do you know which company or companies did that initial environmental analysis?

BETH: From the records I’ve reviewed, most of the environmental work done prior to 2006 was done or supervised by the Traverse Group and ECT Environmental. In 2008, AKT Peerless was contracted to create our Brownfield Plan and supervise our environmental work.

MARK: OK, as we were discussing earlier, when Biltmore backed out, and we started the process of looking for a new partner to develop the property, we successfully secured state and federal grants to both tear down the structures that were still standing on the property and address a number of those areas identified as having contamination issues. And with those grants, as I understand it, we were able to remediate all of the significant areas of contamination except for two. Is that correct?

BETH: Yes, that’s correct. There are two large areas that still require significant work. And the amount of work they require has evolved with the changing standards.

MARK: Where, specifically, are these two area?

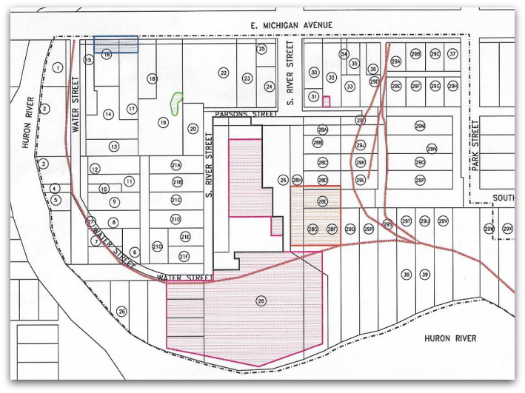

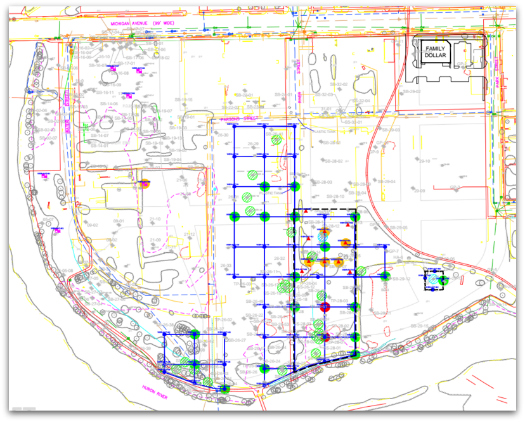

BETH: See the following map. It’s still a draft, as the accompanying DDCC has yet to be approved by MDEQ, but you can see the areas we presently think need remediation. This map, I should add, is still being finalized, as lab results are still coming in, and as additional testing is going to be done.

[The above map, which can be found larger here, was just made public today, and reflects the results of the new testing that has taken place to date. The legend can be found below.]

MARK: Which brings us to the parcel along the southern edge of the Water Street property that Indiana-based developer Herman Kittle expressed interest in for the affordable housing project they planned to call Water Street Flats. Things, it would seem, were advancing relatively well, in spite of some citizen pushback against the idea of building more affordable housing downtown, when the Michigan State Housing and Development Authority (MSHDA), a few months ago, issued a letter stating that, in their opinion, we didn’t appreciate how bad things were on the site, or have an acceptable plan as to how to move forward safely with construction.

MARK: Which brings us to the parcel along the southern edge of the Water Street property that Indiana-based developer Herman Kittle expressed interest in for the affordable housing project they planned to call Water Street Flats. Things, it would seem, were advancing relatively well, in spite of some citizen pushback against the idea of building more affordable housing downtown, when the Michigan State Housing and Development Authority (MSHDA), a few months ago, issued a letter stating that, in their opinion, we didn’t appreciate how bad things were on the site, or have an acceptable plan as to how to move forward safely with construction.

BETH: They were both insinuating the contamination was worse and more widespread than what we had identified, and that we were not taking any caution in preparing for a housing development that would have direct contact with the contamination… Additionally, and this is important, MSHDA was basing their critique on standards that are not in any state (MDEQ) or federal (EPA) rules. Furthemore, they were imposing standards higher than these environmental authorities. MSHDA also wanted to regulate activities beyond the HKP development, which again falls to the MDEQ.

MARK: And the reason MSHDA is involved at all is because they’re contributing money toward the building of the HKP development, correct?

BETH: Yes, MSHDA provides tax credits for the project, which are federal dollars, and they are responsible for approving all aspects of the project.

MARK: And on what did MSHDA base their claim that the “contamination was worse and more widespread”? Had they done a study of the site on their own?

BETH: I’m unsure. If they did any study of the site, it has not be provided to us. It’s reasonable to say, though, that conflicting documents available on the City’s website, and on historic maps, could have led them to that assumption.

MARK: OK, so they likely saw conflicting reports issued by the City over the past several years, which gave them cause for concern. Would I be correct to assume that all of our public information concerning Water Street is now being changed to reflect our most recent data?

BETH: Yes, we are developing new documents and maps and updating data as it is approved.

MARK: Speaking of our most recent data, this past November, after the MSHDA challenge was raised, Ypsilanti City Council agreed to pay its environmental consultant, AKT Peerless, $50,000 to test the site’s soil and analyze 20 years of existing environmental records to determine definitively what cleanup is still needed. This report, as I understand it, was just recently delivered to the City. What does it say?

BETH: The preliminary report was received last Friday. At this point, the initial results show PCBs closer to the surface and at a higher concentration than earlier reports had shown. Borings done near the new border-to-border trail caused immediate concern to the City and resulted in the closure of the trail, which will stay closed until we can review all of the data more closely and create a plan to resolve any possible issues.

MARK: Just to be clear, the trail itself is safe. It’s the ground on either side of the paved trail that’s the concern.

BETH: Yes, the trail itself is safe, as it’s been capped with asphalt and therefore doesn’t allow for any direct soil contact. However, the City remains concerned that some users of the trail, like children or pets, may venture off the trail and come into direct contact. The standard we’re using is the residential standard, which is based on contact of more than 335 hours in a year. We realize it’s not likely that trail users would have that much contact with the surrounding soil, but we want to be cautious. In the past, the City has been defensive and reactive, and we didn’t want to take that approach this time.

As far as other areas of contamination, we will be working with our consultants to create a comprehensive action plan to address areas of concern and limit direct contact by anyone in the area.

MARK: Just so I’m clear, the new report shows PCBs in areas where no PCBs had been identified in the past?

BETH: There are PCBs in areas that had not been previously studied… This new study was based on data collected following a grid pattern that was approved by the EPA. The thing with PCBs and lead is that they can be very localized, limited to just a very specific area, and the previous sampling could have missed the contamination by just feet.

MARK: And this, in your opinion, sufficiently explains the discrepancy between the 2014 brownfield report produced by ATK Peerless, and this most recent study, which they also authored?

BETH: The Brownfield Plan was a compilation of millions of pages of documents created by other consultants. It’s essentially an incentive guide, and not an environmental document. The documents on which the 2014 Brownfield Plan was based are the Document of Due Care and Compliance, which we discussed earlier, and the individual Act 381 work plans. Both of these plans were based on scientific analysis, and required that specific results to be included.

MARK: So, if I’m following you correctly, everything that we’re dealing with now is the direct result of our relying on the Document of Due Care and Compliance prepared by Biltmore?

BETH: I believe so.

MARK: So where does that leave us now? What’s next?

BETH: First, we will be creating action steps to re-open the trail as soon as possible and address the environmental concerns. This will be followed by the creation and approval of the DDCC for the site, which, as we discussed before, is a step-by-step guide for safe redevelopment. Much of the plan will remain the same, though. The goal is to have everything ready for the developers of these sites, who will do the actual remediation work, some of which will be reimbursable through the terms outlined in the Brownfield Plan… And the City will, of course, follow any recommended actions from our environmental consultant and the MDEQ.

27 Comments

I should probably add that Beth and I had wrapped our conversation by the time I received the new map, and, now that I’ve been looking at it for a while, I have quite a few follow up questions that I’d like to ask.

Fantastic. The Trail Project had dozens of volunteers working in those newly identified areas for hours and hours over the past few years. What kind of health effects should we be looking for?

Didn’t people (even on this site) try to claim that there was no contamination at Water Street? That it was just all a conspiracy by Snyder’s cronies to force Ypsi to be placed under an EFM?

I can’t remember, but I remember that being the case. Seems that a Flint like crisis could occur in Ypsilanti for very different reasons.

Why wasn’t a Baseline Environmental Assessment done for 2 West Forrest when it was purchased?

Is it conceivable that Biltmore, who prepared the documents that we’ve been working from for the past nearly two decades, had a vested interest in downplaying the level of contamination?

It looks like the native planting area is completely clean.

I think this disorganization in documentation is an unavoidable consequence of a project that has extended over several years with several changes in administration on both the governmental and private party sides. It was, in retrospect, a project that was a bit too ambitious in reach, and perhaps the best thing to do now is to step back, retire the Water Street debt as soon as possible, and work on other things that could help improve the long term prospects of the city and avoid the imposition of a emergency financial manager.

Thanks, Mark, for this reporting—and thanks, Beth, for laying it all. I appreciate hearing the whole story from the beginning, as well as the information about shifting environmental standards. I learned some things!

Anonymous — a BEA is something a property owner does (or should do) in the process of acquiring a potentially contaminated site. Since that’s a private site, if a BEA was not prepared and submitted to DEQ, only the property owner would be able to say why not.

I share your curiosity, though!

Between people in the city trying to cover their asses and the Ann Arbor News releasing sensationalistic stories, it’s hard to know what the real truth is when it comes to Water Street. Thank you for making an attempt.

I’d love to see this new map with an overlay showing the businesses that had been on Water Street. Specifically, I’d like to know which business was responsible for the high concentrations of lead.

First of all, thank you Mark for being the investigative journalist we so badly need when it comes to in-depth coverage. Also, congratulations to Beth on the difficult, but fine work she is doing. While I agree with most of what jcp2 says above, especially that we need to step back long enough to get all the facts and standards in place to be able to move forward, I do not think we should thwart development opportunities once that has been accomplished. There has been a lot of blame placing when it has come to our difficulties related to this project. It is obvious from this interview that in this and other regards the Water Street property has been a moving target over the years.

Thanks for this guys. Good information to have!

Mr. X — the Ypsi Iron and Metal scrapyard was on the area with the lead concern, at least as the last owner before the city.

Thank you, Murph. I don’t suppose there’s anything to be gained by going after the previous owners of the business, but I like knowing who it was.

I’m not saying to not continue trying to develop Water Street. However, the reason the Water Street development is being pursued is so that the city can increase the tax base to fund adequate city services. Ypsilanti is a small city and constrained by its geography for revenue. Maybe it’s time to reconsider hyperlocal governance because there are things that can be done on a regional level that would enhance quality of life.

Three areas of regional co-operation that could help Ypsilanti out include public safety services, transit services, and (a big reach), school district cooperation. The first would spread out fixed costs while the second and third would increase real estate values.

I have been digging and digging for months trying to find the catalyst involving the Forest/Farm Bureau Brownfield contamination grant. As many know of the PBB poisoning of Michigan thanks to the St. Louis chemical company mislabeling a cattle feed supliment with a fire retardant in 1973. Farm bureau mixed it in and distributed the grain to it’s elevators and distributed tobour cattle/dairy cows. Rumors have it that it was delivered to our Forest Farm Bureau as it closed soon after. All records of delivery locations were destroyed in the cover-up. They were not allowed to brew beer there years back, but we’re not told why. That basement is holding 4+feet of stagnant contaminated water..possibly hundreds of gallons…do you know the cost to barrel that if contaminated? They better not dump it down the hill into our river…I am watching them like a hawk.

Excellent, excellent interview, reporting…please stay on this…

Gosh, will there be a disclosure suit from Family Dollar now? I would certainly have an issue if these items were not disclosed.

Thank you, that is the most unbiased information i have seen to date. Now if only the source where most of us are getting information– The Ann Arbor News — could start reporting facts instead of click bait garbage propaganda we’d be getting somewhere. We can’t even begin to start making decisions as a community if we are not presented with the facts. I am so over the conscious omissions and sensationalist writing that pits our community members against one another. All it does is hold us back.

Thank you for the clarity and history. I sure like walking that trail. Sounds like even good people will have a hard time sorting out the complications. Best wishes.

Why are all the borings in places on the map that show no contamination? Are there maps of previous borings that lead them to the currently mapped contaminated areas, or have they been designated as contaminated merely from surface testing? Have they done borings at the locations where they found surface contamination? Are they planning to?

Why aren’t they testing the banks of the river? This is where the raw waste and sewage from Ann Arbor would get deposited. Their storm drains dump into the Huron after heavy rain.

Why don’t they have a grid map of the entire area and test the entire parcel?

This article is the best information to date, but even after all these years and with all the money spent to date, I fear that we are still just “scratching the surface” in discovering the full extent of the contamination.

Informative interview and new map: thank you, Mark & Beth!

There is no contamination. It is all a conspiracy by Rick Snyder to put Ypsilanti under an EFM and reduce the democratic vote in the 15th Congressional District.

That is the best summary ever! You have done our community a great service.

Wouldn’t it be great if we could read that kind of reporting in the newspapers?

“That is the best summary ever! You have done our community a great service.”

At least that makes one of us, right Cheryl?

Where there’s a will, there’s a way.

“How Contaminated Land on the Gowanus Became a Luxury Housing Development”

Read more:

https://www.dnainfo.com/new-york/20160503/gowanus/how-contaminated-land-on-gowanus-became-luxury-housing-development

HAPPY TRAILS? CITY RECEIVES GRANT FUNDS TO GET BORDER TO BORDER TRAIL OPENED

The City of Ypsilanti has received a grant of up to $200,000 from the Local Site Revolving Remediation Fund (LSSRF) of the Washtenaw County Brownfield Redevelopment Authority (WCBRA) to remediate contamination along the Border to Border Trail at Water Street. Bid documents are being prepared with a projected opening of the trail later in the year. In addition, the required fence around the PCB and Lead contaminated area at Water Street has been contracted for and will be installed within a month. The pedestrian bridge to Waterworks Park from Water Street is in the process of being re-planked using a Building Healthy Communities Grant and should be completed in the next few days. When all is complete the trail will re-open. Looking forward to a walk along the river.

CITY AWARDS CONTRACT TO CLEAN-UP WATER STREET BORDER-TO-BORDER TRAIL – EXPECTED OPENING IN SPRING OF 2017.

The city awarded a contract for not-to-exceed amount of $179,876 to TSP Environmental to clean-up contamination along the Water Street section of the border to border trail. The work consists of removal of sections of contaminated soil along portions of the trail. The work is being done in conjunction with the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ). A grant from the Washtenaw County Brownfield Redevelopment Authority (WCBRA) is financing the clean-up and related costs. Work is scheduled to begin when the frost is gone in the Spring of 2017 and the trail will reopen when completed.

4 Trackbacks

[…] As for the current status of Ypsilanti’s Water Street redevelopment project, I’d encourage those of you who haven’t done so already to read my recent interview with Ypsilanti Director of Economic Development Beth Ernat. […]

[…] civic anchor” that would help us jumpstart meaningful development on our 38-acre downtown brownfield known as Water Street and turn our city around. Well, despite his assurances at the time at he was […]

[…] to construct what was a thriving public sculpture garden on the site. And, even though digging in the contaminated soil may end up taking years off my life, it’s still one of my favorite places in the entire world. […]

[…] have been pushed out by city governments in crisis, as Ypsilanti has, citing liability for the toxicity of that zone, about which much ink has been spilled ranging from hope to corruption. Others, like the Dudley […]