Almost five years ago now, I interviewed a new transplant to Ypsi by the name of Lee Azus as part of our ongoing Ypsilanti Immigration series. Azus, a former San Francisco bookstore owner, as you might recall, was anxious to hit the ground running and really get to know this community which he had chosen to become a part of. Well, since then, Azus has been keeping himself busy as a graduate student working in the areas of historic preservation and architecture, and doing research into the history of Ypsilanti’s ever evolving residential landscape. And, this coming Monday evening, at 6:30, he will be presenting some of his ongoing research into the changes Ypsilanti’s Southside experienced in the 1960s as a result of so-clled “urban renewal” efforts. I’m afraid the following exchange with Azus will be infinitely unsatisfying to some of you, seeing as how we just begin to scratch the surface, but, as his presentation is coming up in just a few days, we just didn’t have time to go too deep… Fortunately, though, if you want to know more, all you have to do is show up at the downtown library this Monday evening and join in the conversation.

“In 1952, the city of Ypsilanti took the first step towards an Urban Renewal project to combat what it called ‘blight’ and ‘slum’ conditions on the Southside—the area south of Michigan Avenue. From the beginning, the Urban Renewal program divided opinions in the African-American community as to the best way to improve social and economic conditions on the Southside. Residents were faced with forced eviction, while being unable to move into other Ypsilanti neighborhoods outside the Southside due to legalized housing segregation. As hundreds of homes were destroyed, there was no rush by developers to build new housing or businesses as the City had promised. It was only after 1997 that the last large parcel of land was developed.” – Lee Azus

MARK: How is it that you came to be interested interested in Ypsilanti’s history relative to urban renewal?

LEE: I had been doing research on the Brewster-Wheeler Recreation Center in Detroit, which is the one remaining building around what had been Hastings Street, the main business thoroughfare of the city’s great African-American neighborhood, Paradise Valley. And that led to a comparison to the ABC-Polk Brothers Recreation Center in Chicago, the story of which my father had often recounted to me. (Its origins lie in the Leopold and Loeb murder of Bobby Franks, and the subsequent donation of money by Bobby’s father for a boys’ recreation center in my dad’s neighborhood. But I digress.) So, when I was in a Historic Preservation “Building Systems” class at Eastern Michigan University, I chose another recreation center, the Parkridge Community Center on Harriet Street, to look into. And I found the history of the controversy around its construction to be incredible… Anyway, when I interviewed some of the neighborhood elders at their weekly card game at the Community Center, I was introduced to the story of the urban renewal program on the Southside, which was clearly a pivotal moment in the lives of those in the generation that married and started families here after World War II. And, later, when I was working on a different project concerning the Federal Housing Administration and the shaping of the suburban landscape, I couldn’t help but make the connection between the segregation that the FHA encouraged in its mortgage underwriting policies, and the segregation of Ypsilanti. So I returned to the story of urban renewal and wondered what exactly happened here. And that’s what got me started.

MARK: As I understand it, prior to Ypsilanti’s urban renewal program, there was a thriving black business community on Ypsilanti’s south side, along Harriet Street. Was it this urban renewal project that we’re now talking about that killed it?

LEE: That’s a complicated question. Yes, there was a business area on the Southside, which was centered along Harriet Street. There were also stores and a pool hall on South Huron Street, and businesses on Monroe, and Jefferson. Unlike along Michigan Avenue, some businesses there began in homes, which, because of the lack of zoning, then became commercial properties. While, through the 1930s, there was a pool hall and a bar, as well as barbershop on Monroe owned by Mr. Fletcher, it was only during and after World War II that the number of businesses on Harriet Street really increases. This was due, in part, to the huge migration into the neighborhood during the war from families moving up from the South.

Not all of these businesses were destroyed during urban renewal, though. The northern boundary of the Parkridge Urban Renewal Area, as it was officially called, cut through the center of Harriet Street. The businesses on the south side of the street were doomed, basically. Those on the north side, however, were not affected. In fact, even after the businesses on the south side of the street were demolished, the number of businesses on the north side of Harriet remained fairly stable well into the 1980s.

While the commercial district was affected, the heart of the story wasn’t really the destruction of the Harriet Street business district, as I’d originally thought that it would be. Both “urban renewal” and “urban redevelopment” were legal schemes to redevelop residential areas that the local government had determined to be “blighted” or “slum-like.” Those aren’t arbitrary terms; the government actually had to make those declarations to begin the process to get federal housing funds. “Urban Renewal” was a product of the Housing Act of 1954, and it was a huge win for the building and real estate industries, which could finally reverse the course of Truman’s Housing Act of 1949, which called for 810,000 units of public housing to be built over five years. While Truman called for “slum clearance” through wholesale flattening of neighborhoods, under Eisenhower, the term “urban renewal” was introduced to signify a more holistic approach centered around conservation, selective clearance of property, and infrastructural and cultural improvements. While that sounds way better than the earlier version, the Eisenhower version was crafted by the building and real estate industries to give the private sector a greater role in redevelopment.

[above: 566 Jefferson Street. Demolished 1970.]

MARK: Have you, through your research, been able to identify exactly when this idea first surfaced here in Ypsi, or how the decision was ultimately made, and by whom?

LEE: The first scheme began in 1952. The city applied for a grant of around $6,000 to conduct survey work for a redevelopment program. And it wasn’t supposed to just be about the area south of Michigan Avenue, at least at the outset. With that said, I’ve only been able to find one article that makes mention of the city even considering a neighborhood north of Michigan Avenue for redevelopment. That would have been the area bounded by Cross south to Michigan Avenue, and River Street east to Grove. But, other than that one article in The Ypsilanti Daily Press, it seems that all consideration was given to the Southside. The city eventually chose the area bounded on the north by Michigan Avenue; on the south by Harriet Street; on the west by First Avenue; and on the east by Hawkins Street. This portion of the South Side was labeled a “slum,” where the houses “almost without exception… appear worn-out and dilapidated.”

MARK: So, this started in the early ‘50s?

LEE: That’s when the discussion started, but the city dropped this first plan. The conversation, however, started up again in 1958 under the new terms of the Housing Act of 1954, which made the promise of federal funds too good to pass up. Under a provision called “grants-in-aid,” new public buildings, like new schools, or infrastructural improvements that would affect at least ten percent of the targeted urban renewal neighborhood, could count as the city’s one-third contribution towards the urban renewal program. And, in cities with under 50,000, like Ypsilanti, the city had to contribute only one-fourth the cost of the program. So 1958 was significant because the voters had just approved the building of two new junior high schools. And the new police station on West Michigan Avenue was being built then as well. Taken as “grants-in-aid,” the city could credit these buildings as their share towards urban renewal and pay basically nothing for the proposed renewal work. In actuality, it didn’t quite turn out that way… but it’s fair to say that the urban renewal plan that was rolled out in the 1960s had its genesis with those new junior high schools. Even the new boundaries of the Parkridge Urban Renewal Area were indebted to those schools. The 1952 plan, and even a 1960 plan that the City Council considered, the boundaries were north of Harriet Street, while the Parkridge plan was from Harriet Street south to the I-94.

MARK: In addition to looking at historical documents, did you talk with many people who were actually involved in either making the decision to redevelop this area, or fighting against it?

LEE: I haven’t met anyone who was involved in either making the decision or fighting against it. I have met a woman, however, who lost her home on Goodman Street, and a man who went to East Junior High School after it opened. Mr. Currie, the owner of Currie’s Barbershop, was involved with the Ypsilanti Business and Professional League, the group that partnered with Brown Chapel AME Church to get the Parkview Apartments built on the south side of Harriet Street. He is as close as I’ve come to interviewing an actor in the shaping of the neighborhood. But, I’m still talking to people who lived through that period in the neighborhood.

MARK: But you did find evidence of people fighting against this, correct?

LEE: Yes. The biggest opponent to urban renewal was Mrs. Mattie Dorsey, who has long since passed away. Everyone I talked to remembered Mrs. Dorsey’s fight again the program. She went to over 200 consecutive City Council meetings and always managed to call for the program’s immediate halt. She once led fifty supporters in songs to disrupt Council from voting on urban renewal legislation. Luckily I found some of her mimeographed newsletters. And, The Ypsilanti Press loved to quote her at length, because she was incredibly smart and witty. I think The Press quoted her to make her seem eccentric, but I don’t read it that way, especially with hindsight.

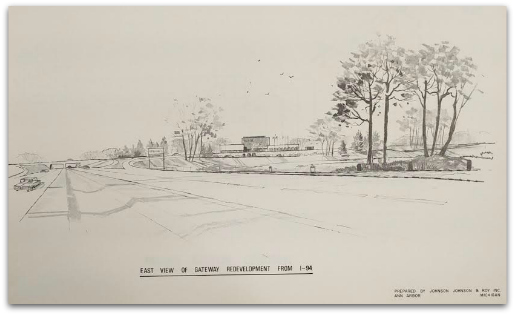

[above: A proposal for the 10.6 acres between Huron and Hamilton as seen from I-94 westbound, approaching the off-ramp.]

MARK: I suspect, as with most things, there wasn’t just one single reason why this moved forward. My guess is that there were some who were truly concerned about the health and safety of people living and working on the Southside. And, as you mention, it appeared as though there was free federal money to go after, which I’m sure helped convince others. In addition, I assume some were probably motivated by the prospect of both reining in the black community and driving more business to the primarily white merchants along Michigan Avenue. I’m curious to know your sense as to why things played out like they did, and what the contributing factors were.

LEE: This is the most difficult and complex question because there was a structural problem around housing and lending discrimination against African-Americans. What could the community do when it was shut out of the credit market, when FHA-backed mortgages were not available to them, and the infrastructure – sewers, sidewalks, paved streets – lagged behind other parts of the city? Where does self-interest collide with altruism? All of the African-American leaders and major property owners on the Southside supported urban renewal. Sure, they had reservations. Councilmember John Burton went back and forth, although he mostly supported it. They knew how many people would be displaced with no plan to relocate them. (Displaced black residents couldn’t just move into a house north of Michigan Avenue, except maybe on Norris Street.) But, given all the factors at play, it seemed to many like a good deal.

So the city recommended 250 low-cost rentals, a fraction of which were actually built. (They got 144 units at Parkview Apartments and others at Arbor Manor.) They also wanted 40 new units of public housing, which they eventually got. And they had plans for more.

The Chamber of Commerce and the Ypsilanti Industrial Development Corporation were big supporters of the urban renewal project and saw it as the first step towards other projects around Michigan Avenue. The big one would have been the “Heritage Square” neighborhood (Huron to River Street, Cross to Michigan) and a new Greek Theater, which was to be built on the site of the old Ladies’ Library on North Huron at Washtenaw.

As for your comment about driving business to Michigan Avenue, you know the Huron-Hamilton interchange onto I-94? Until it opened in 1972, the on and off ramps were on Grove Street, convenient to the Ford plant and other industries. How did the Huron-Hamilton interchange get built? Not only did it get built, Huron and Hamilton, Washtenaw and Cross Streets were changed into one-way streets to feed the traffic flow. Now, Dan Boatwright, who lived on West Cross and was head of a homeowners’ association, allied himself with Mattie Dorsey and started a revolt against the traffic changes. They called it “a gift to Central Business District” (Michigan Avenue), where sales had been declining since 1957. Obviously, the neighborhood associations lost, but Boatwright then ran for City Council, and then became mayor.

MARK: I’m not sure to what extent you’ve looked at other black communities in the midwest and how they were affected by urban renewal, but I’m curious to know your sense of how unique the events that took place here were.

LEE: I can’t speak to small town urban renewal plans other than Ypsilanti’s. Detroit’s story is well known, and began with the clearance of parts of Paradise Valley in the 1930s for the Brewster Homes, a segregated public housing project. The building of the I-75 and Chrysler freeways, and the destruction of Black Bottom to build Mies van der Rohe-designed Lafayette Park were huge clearance projects, not selective clearance as in Ypsilanti’s program. Thinking about Chicago, San Francisco, and Atlanta, their urban renewal projects were more similar to Detroit’s, not Ypsilanti’s. But, while the landscape looked different between Ypsilanti and the large cities, the structural underpinning of social and economic discrimination ultimately united all these urban renewal projects.

MARK: It’s difficult to talk about established black districts being destroyed and not think about what happened in Tulsa in 1921, where America’s most prosperous black community was burned to the ground. While I don’t know that it really factors into the Ypsilanti story, as they were completely different circumstances, I do think it’s important to note that we have a history in this country of undermining and destroying black business districts.

LEE: Here, in Ypsilanti, the Harriet Street district was not an economic threat to Michigan Avenue interests. Arborland, Gault Shopping Center (by the old off-ramp on South Grove), and the new K-Mart and strip malls opening on Washtenaw Avenue, were what finished off the legacy businesses in downtown Ypsilanti, and the business owners knew it. I do think, however, that, as the urban renewal program was originally conceived (in 1952 and 1958), starting at Michigan Avenue and going south to Harriet, it was an opportunity to increase property values in the area immediately surrounding the Central Business District, which could only be a plus for Michigan Avenue business.

MARK: I saw it mentioned online, in a post about your upcoming presentation, that 190 families were relocated as a result of Ypsilanti’s urban renewal initiatives. Where were they relocated to?

LEE: I’m having a hard time finding out where all the residents went. I found a 1969 list of new addresses of relocated people, but who knows if those people found permanent housing, or were just living provisionally until the urban renewal programs’ promise of new homes would finally be realized? (Parkview and Arbor Manor were completed in the early ‘70s, so I suspect and hope that those who managed to hold out that long may have remained in the neighborhood once the new apartments were opened.) The woman I interviewed who owned a home on Goodman, bought a home on Ferris, which was a short walk away. My friend Janice’s grandmother moved from Jefferson Street to either Pittsfield or Ypsilanti Township, I forget which. A good number of people did move to the Willow Run area, I think. I need to do more research on that question. The Urban Renewal program was officially over in 1974, even though there were still lots of empty parcels on the Southside. So, the trail kind of grows cold, at least in terms of official documents.

6 Comments

It was, as Azus points out, a complex situation. Most black leaders at the time, if not all, enthusiastically supported the program. Their situation was bad, and it was made worse by the discriminatory practices that kept them from leaving the south side.

I’d like to know how the property was taken, and who owned it after the “blighted” homes were demolished. Would I be right to assume that home owners were compensated for their properties, and then the city sold the cleared land to developers?

How much things have changed over 50 years.

Here’s a headline from today.

“America’s top banks gave Oakland’s black borrowers just four home loans in 2013. Four.”

http://fusion.net/story/273367/california-oakland-black-hispanic-lending-report/

4 out of 7 applications.

They weed people out before they ever get to the application process.

It is hard to say what would or would not have happened.