For this, the seventh in the Art, Food, Sex and Trauma series, I’ve decided to reach out to my friend Chris Hyndman, who, when he’s not teaching art at Eastern Michigan University, can generally be found painting wonderfully complex fox-head-covered tartan patterns on canvas in his Chicago studio.

MARK: You’re a Canadian, right?

CHRIS: Yes, I’m a Permanent Resident of the U.S. (a “green card” holder) and a citizen of Canada.

MARK: There’s another famous Chris Hyndman in Canada… a television host or something…. right? Is that why you had to leave the country? Was there too much confusion?

CHRIS: Yes, the “Designer Guy” Chris Hyndman. He’s way more famous than me… and way more stylish. To find me on Google you need to add some qualifiers, like “painter” or “artist.” Otherwise, it’s all him. He had a popular show on Home & Garden Television, “The Designer Guys,” with Steve Sabados. It was an interior decorating makeover/advice kind of show. Last I noticed, he’d transitioned to something closer to a general lifestyle show, which I think is called “Steven and Chris” or “Chris and Steven.” I’ve never watched more than about 30 seconds of either show. Last year I was invited to speak at a decorator flooring trade show, by someone who must not have looked very carefully at my website when they visited for my email address. It was tempting to play along, but I couldn’t bring myself to follow through on the lie; It seemed impolite and un-Canadian.

MARK: So, what brought you to America, if it wasn’t that you were forced out by the Designer Guy?

CHRIS: I left Canada to go to grad school in Ohio and one thing led to another and I never really returned. Now I’m married to an American citizen and have a mortgage, a dog, and a full-time job. I can’t see myself returning to Canada anytime soon, except to visit family.

MARK: Your art, over the time I’ve known you, has shifted a bit. When I first met you, if I recall correctly, you were creating sculptural paper pieces, kind of three-dimensional, tangram-looking things. More recently, though, you’ve moved on to something different… I’ve been struggling to find the right words… The best I’ve been able to come up with is “anthropomorphic textiles.” Is that close?

CHRIS: It’s fun to hear you say that—both the “anthropomorphic textiles” thing, and hearing that your first experience with my art was the three-dimensional paper stuff. The three-dimensional paper and tape work was an anomaly for me, a kind of break from the plaid paintings that I was making—and a response to a specific incident involving my dog. People seemed to really like that work and I’ve been asked many times if I plan to continue it.

CHRIS: I’ve tried, but for me it was always a short-term, subject-specific thing and I haven’t found another motivation to drive it. I suppose that my use of tissue paper in more recent paintings is a result of something that started in those dog pieces. Before them, I hadn’t used tissue paper in anything but a few experiments, nothing serious, whereas now it’s in most of what I make. I’m rather charmed by the nature of its color… and that it fades so aggressively with time and exposure to light.

MARK: Before we go any further, is “anthropomorphic textiles” a pretty good descriptor of your recent work?

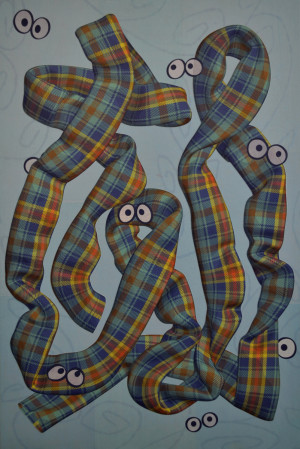

CHRIS: Yes, it seems like a good fit for the recent paintings. Can I use it? Lately, I’ve been calling it “zombie fabric” and populating the paintings with eyeballs, and hands, and fox heads. In the painting I’m working on now, the fabric form is “standing,” spot-lit, on a stage.

MARK: How did you come to start painting images of fabric?

CHRIS: I came to fabric through an interest in tartan patterns, what we tend to call “plaid.” The patterns seemed so ubiquitous in North America—flannel work shirts worn by construction workers and grunge rockers, skirts worn by school girls, tablecloths and gift wrap sold by Martha Stewart, mousepads, desktop wallpapers, and probably a few things in everybody’s closet. And no matter which of the thousands of tartan patterns we see, the recognition of it and naming of it as “plaid” is nearly instant. It’s an incredible reduction, not only in terms of meaning, but visually too. All of that color and the specifics of proportion and sequence—things that might fascinate a painter—all of it gets reduced in a fraction of a second through a type of recognition that renders additional looking or sustained attention unnecessary. I thought it would be interesting to make paintings that embodied that operation, that kind of “blanking”—paintings full of specific and interesting color interactions that by virtue of being plaid—not pictures of plaid fabric, but plaid pictures—blanked themselves out. I thought that if it worked, if I got it right, I could make lots of them, and amplify the operation by showing that differences between the patterns don’t thwart the blanking.

MARK: And then things evolved from there…

CHRIS: Yes. Eventually I grew tired of making the same type of painting, with the same type of planar pictorial space. So I started introducing a more volumetric type of space by “warping” the patterns, using software, before I made the paintings. It’s funny, but at the time, it didn’t strike me as a move toward fabric. Now it seems obvious, but I’d spent years thinking about plaid as pattern, quite apart from plaid as fabric. Once I started warping the patterns using basic techniques in Adobe Illustrator, it didn’t take long before I realized that if I wanted a more dynamic volumetric space in the paintings, I needed to use 3D modeling software. So I learned enough of Autodesk Maya to start making basic cloth animations, which serve as image sources for the paintings. Sometimes people are surprised to hear that I don’t use photographs of fabric or have piles of plaid fabric in my studio. Aside from the canvas that I paint on, I don’t have any fabric in the studio. It’s all simulated.

MARK: And, then, you started adding hands, eyeballs and fox heads. How, exactly, did you arrive at those three things?

MARK: And, then, you started adding hands, eyeballs and fox heads. How, exactly, did you arrive at those three things?

CHRIS: When you first launch it, Maya presents you with a curious paradox. It’s incredibly full and unsettlingly empty at the same time. Full in the sense that it seems capable of simulating anything—all of physics, all of light’s possibilities, any material you can think of… it all seems to be in there, as potential and a type of power. But you start with the greyest and emptiest of voids, and maybe a grid that suggests a ground plane. I kind of knew where I wanted to end—the kind of result I was looking for—but what action or series of simulated events would lead me to the fabric form that I wanted? I needed a narrative to get things underway. Not long before I started working with Maya, I’d been looking at stills from Dudley Do-Right cartoons, for background ideas for a painting that used the Royal Canadian Mounted Police tartan. I’d even started watching the cartoons with the primary purpose of collecting stills on my computer. I love the severely simplified backgrounds. And the animation is really limited, like 4 cells per second, which means that stills from “fast action” sequences are pretty crazy: a dozen eyeballs, a half dozen hands, weird hybrid shapes. So small bits of action from Dudley Do-Right cartoons became a starting point for me in Maya. I’d use a simulated fabric object as a character stand-in and then try to replicate the bit of action from the cartoon scene. Although you can’t see it in the finished paintings, the Dudley thing was a means to an end for a long time—enough of a narrative to get things started for me in Maya. But over time I came to see the whole enterprise, and the Dudley character, and the cartoons, as a kind of analogue for the way I was making and thinking about my paintings. At some point, a couple years ago now, it seemed right to start including cartoon elements in the paintings… hence the hands, eyeballs and fox heads. They’re all from Dudley-Do Right cartoons.

MARK: Several months ago, we had a conversation here on the site about EMU’s Art department. An article had come out claiming that an art degree from EMU is a waste of money. And I took exception to the claim, pointing out where I thought their reasoning was flawed, and several folks in EMU’s Art Department weighed in. I don’t believe, however, that we ever heard from you. Were you aware of this article? And, if so, what did you make of it?

MARK: Several months ago, we had a conversation here on the site about EMU’s Art department. An article had come out claiming that an art degree from EMU is a waste of money. And I took exception to the claim, pointing out where I thought their reasoning was flawed, and several folks in EMU’s Art Department weighed in. I don’t believe, however, that we ever heard from you. Were you aware of this article? And, if so, what did you make of it?

CHRIS: Yes, someone tipped me off to it via Facebook and I followed the conversation, albeit silently, on markmaynard.com. I was swamped with preparing work for a show and didn’t feel that I could contribute anything pertinent unless I gave it some time. I also questioned whether it was worth it, personally, to get wound up about a narrow and stupid claim. At the time, you called it “total bullshit,” which seems about right. As someone who makes paintings, I’m familiar with claims that an investment of time, money and energy in artmaking is foolish. Those who think so are unlikely to be swayed by anything that I have to say… and doing so just means less time for painting. That’s selfish, I know, and in hindsight I regret not saying something about the Atlantic article. On behalf of current and former EMU art students, I should have offered some push-back.

MARK: So, now that you’ve had some time to think about, is there something that you’d like to add to the conversation I had online with your fellow professors?

CHRIS: Well, just about everything these days is seen through an economic lense thanks to our generally weak economy, conversations about income disparity, the unemployment problems of the past several years, etc. In that kind of environment, we tend to hear a lot, via the media, about how those with a college degree earn considerably more over their lifetime than those without; that not going to college means significantly limiting your lifetime earning potential. Additionally, we hear that the “jobs of tomorrow” will require graduate-level education, and that even now, an undergraduate degree is not enough to be competitive. And so it is that the value of a university degree gets tied—by articles like the one in the Atlantic—to earning potential, and the point of attending a university becomes about being competitive in the job market. Through a lense like that, universities are viewed—and sometimes behave—as vocational schools, community colleges, or part of a jobs scheme, instead of like academic institutions where scholarship, research, thoughtful debate and intellectual growth are valued and invested in for their own sake. And there’s the rub: Universities are, in actual fact, still closer to the latter than the former. I think the issue of value, when it comes to a university education, is complicated, not least because the people invested in that education and/or its valuation (students, parents, faculty, administrators, employers, politicians, taxpayers, the media, etc.) have differing and maybe contradictory opinions about what a university is—what it’s for, what it should do, how it should operate—and further, how it should or shouldn’t be similar to a community college or vocational school. I’m not suggesting it’s unhealthy to entertain a variety of viewpoints, but when institutions themselves seem confused or even duplicitous about what they’re doing, and families and young people have tens of thousands of dollars—or the equivalent in debt—in the balance, it’s not surprising that the conversation gets heated.

Parents and students are willing to pay tens of thousands of dollars for the promise of jobs and a higher lifetime earning potential, but not so readily for something fuzzier sounding, like learning or growth, or something that hinges more on engagement than on simply paying the tab. A university education is four or five years in a learning environment that promotes critical thinking, creative problem solving, and exposure to diverse and challenging ideas. It’s an environment that demands and fosters strong communication skills, strong social skills, strong research skills, strong organizational skills, and the ability to manage and prioritize one’s time and energy… to say nothing of nurturing an understanding of how one learns and an appreciation of learning as a lifelong endeavor. I’m guessing that a student who takes full advantage of that environment—who engages it fully, rather than seeing it as a box to check on the way to a job, or a resume line—will eventually find their way in the world. That’s what one pays for: the education and the experience, not the degree. And it doesn’t matter if you’re in Engineering, Literature, or Dance, the skills are real and long-lasting, and probably attractive to employers too. It seems to me like the opposite of “a waste of money.” It bears mentioning, of course, that you’re also paying for my salary and benefits, and those of my faculty peers, and an ever-increasing number of administrators, and a head football coach who makes more in one year than I do in five… The cost of a university education today is much too high, especially in light of how it’s marketed to those with limited finances, limited preparation, and life pressures that make graduation—to say nothing of long-term postgraduate security—a real struggle.

Because as much as I believe what I’ve said, I also recognize that it’s too romantic. It’s the kind of thing a white guy from a privileged background, with a tenured teaching job says. It glosses over the financial realities of peoples lives, and even the financial realities of operating a university. Someone from a family that can’t afford to support their education, who emerges from college with thirty thousand dollars in debt and can’t pay for meals doesn’t have the time to “eventually find their way in world.” Someone who is the first in their family to attend university may not have a sense of what they’re taking on or a strong awareness of how to make the most of it. Someone paying their way with two part-time jobs, or kids, or both, and barely enough time to attend class—let alone study properly—how do they make the most of their university opportunity? What about students who find themselves admitted, but don’t have the preparation—for a variety of reasons—in reading and writing to make it through a freshman class, let alone a degree program? I should stop there. I don’t have solutions for any of it, and that string of rhetorical questions is probably a sign that I’ve headed toward a diatribe, instead of a conversational reply to an interview question.

MARK: The name of this interview series is “Art, Sex, Food and Trauma: Mark Maynard shoots the shit with the most important artists of our day,” and we’ve yet to hit on sex, food or trauma. Shall we talk about trauma? Have you ever had a near death experience?

CHRIS: The most traumatic near death experience I’ve had involves my dog, Gryphon. It was the event that prompted the artwork I mentioned earlier. He and I were standing in our front yard when a friend of mine who had come to the house for a visit drove away in her van. Gryphon took off like a dog possessed and before I could catch up, or even get close, he was following the van around the corner and into traffic on Hewitt Ave. In that particular spot, Hewitt is four lanes, hilly, and 45 mph. As I reached the end of the street, running full bore, I heard screeching tires and horns and fully expected to see my dog get hit by a car, or find him already mangled and lying in the road. I still shudder when I think about it; the images in my head are awful. Amazingly, everybody missed and I was able to run into traffic and grab him. I carried him back to the curb and sat in the grass at the side of the road shaking and sobbing. I don’t think I’ve ever been more scared or more grateful, simultaneously, in my life. The thought that I could have seen Gryphon violently killed and that my own carelessness, not having him on leash, was to blame… that I nearly killed my dog—this creature that I love and who needs me to look out for his safety in a world that he can’t fully understand… I don’t think I would ever have forgiven myself. As much as I hate them, I think the horrible images I imagined and the anxiety they still provoke are mild punishment for my stupidity on that day.

CHRIS: The most traumatic near death experience I’ve had involves my dog, Gryphon. It was the event that prompted the artwork I mentioned earlier. He and I were standing in our front yard when a friend of mine who had come to the house for a visit drove away in her van. Gryphon took off like a dog possessed and before I could catch up, or even get close, he was following the van around the corner and into traffic on Hewitt Ave. In that particular spot, Hewitt is four lanes, hilly, and 45 mph. As I reached the end of the street, running full bore, I heard screeching tires and horns and fully expected to see my dog get hit by a car, or find him already mangled and lying in the road. I still shudder when I think about it; the images in my head are awful. Amazingly, everybody missed and I was able to run into traffic and grab him. I carried him back to the curb and sat in the grass at the side of the road shaking and sobbing. I don’t think I’ve ever been more scared or more grateful, simultaneously, in my life. The thought that I could have seen Gryphon violently killed and that my own carelessness, not having him on leash, was to blame… that I nearly killed my dog—this creature that I love and who needs me to look out for his safety in a world that he can’t fully understand… I don’t think I would ever have forgiven myself. As much as I hate them, I think the horrible images I imagined and the anxiety they still provoke are mild punishment for my stupidity on that day.

MARK: And how did that experience manifest itself in the folding of paper?

CHRIS: Yeah, that probably seems weird… It happened during the summer, when I work in the studio full time, hours every day. I couldn’t stop thinking about it and the images of Gryphon wouldn’t leave my mind. It seemed like the only way to deal with it emotionally and stay productive in the studio was to sort out something new… take up a challenge that demanded a certain kind of problem solving and focused attention, like a math problem. Anything contemplative and open-ended just got railroaded by dead dog images. At that point, it was still very early days for me with Maya, but I’d poked around enough to understand that objects in Maya, for the most part, are composed of mathematically defined planar triangles—hundreds of thousands of them in the case of complex objects, and crazy small triangles sometimes, but basically that’s it in terms of structure. Cars, fabric, dogs, cats, people, trees, you name it… just triangles. Which at some point, pre-dog incident, got me thinking that you could build in real space, like a model kit, anything you could make in Maya’s digital space… as long as you could make all the correct triangles and put them together in the proper way. And you could do it with the simplest of materials: paper, tape, and the odd bit of glue. This was a little before the 3D printing craze and I liked the idea (still do) that it could be a home job; no special gear needed beyond the software. The only limits are your patience and your capacity to sort out some math. So I wrote a script to explode any polygon-based Maya object into its constituent triangles, and organize and orient the triangles in a way that would let me render them out with an orthographically defined camera at a consistent scale. From there I could print out the separate little triangles with my desktop printer and cut them out with an x-acto knife… and… eventually (lots of triangles)… tape them together in the right way to make a real-space version of the object. It’s a bat-shit crazy way of making something, but my need for that kind of problem solving, right after the dog incident, made it seem like just the thing. In hindsight, wearing my pop-psychology glasses, it seems obvious that I found a way to dwell on the incident for the necessary time, without consciously framing it for myself as that. That’s why I mentioned earlier that the paper and tape stuff remains a one-off for me. It was driven by a particular, coping-related motivation.

MARK: OK, so according to the terms agreed to, you’re obligated to also answer questions about sex and food. Do you have a preference as to which we address first?

MARK: OK, so according to the terms agreed to, you’re obligated to also answer questions about sex and food. Do you have a preference as to which we address first?

CHRIS: Sex before food for sure.

MARK: Did you first learn about sex, as I did, from Degrassi Junior High?

CHRIS: Ha! I never really watched Degrassi, which is probably more embarrassing to admit than talking about sex. The Canadian television thing is an ongoing embarrassment for me. It comes up a lot. People here in the US find out I’m from Canada and its the second or third thing they want to know about: Did I watch SCTV or The Kids in the Hall or Degrassi Junior High growing up? It’s a real conversation killer at parties when I say, “No, not really,” because the person asking is usually a big fan of the show and hoping to share their enthusiasm. And I can’t fake it, because the person knows far more than I do about the show and the characters and the gags and the catch phrases. Inevitably, I end up apologizing for being a bad Canadian… which is very Canadian actually. Another part of it, I guess, is that I never really thought of those shows as “Canadian” when I was young. They were just television shows, like other television shows. Bob and Doug MacKenzie weren’t satirical Canadian stereotypes to me; they were just funny guys drinking beer and saying, “Take off, eh!” I suppose I wasn’t very clever. And I think it’s hard to fetishize the cultural material of one’s homeland in the way one might with the cultural material of other places; Canadiana isn’t exotic for me the way it can be for non-Canadians. Well, that wasn’t really about sex, but I did say “it’s hard,” “fake it,” “fetishize” and “exotic.”

MARK: Why isn’t poutine more popular here in the States?

CHRIS: Well, I won’t say the States has the market cornered on eating fatty food, but it does seem like a popular activity here… and what better meal in that respect than french fries with cheese curds and gravy? I suspect it also has something to do with poutine being a French Canadian tradition, by which I mean that its popularity in Canada is more provincial than national. Although you can get it at McDonald’s.

CHRIS: Well, I won’t say the States has the market cornered on eating fatty food, but it does seem like a popular activity here… and what better meal in that respect than french fries with cheese curds and gravy? I suspect it also has something to do with poutine being a French Canadian tradition, by which I mean that its popularity in Canada is more provincial than national. Although you can get it at McDonald’s.

MARK: If you could have one meal over again, from any point in your life, what would it be?

CHRIS: That’s a tough one, mostly because I’m not really a food guy. Our mutual friend, Amy Sacksteder, for example, becomes giddy with excitement—bounces up and down and claps her hands—at the mere mention of certain meals. That’s not quite me. Although Amy would tell you I have a similar reaction to chocolate milkshakes.

My father used to make a lobster dinner for our family each New Year’s Eve. It was pretty simple, just boiled lobsters and melted butter, with a caesar salad. He passed away a couple of years ago and I think of him sometimes cooking the lobsters in his giant pot on the stove. I miss those meals.

[Here’ve video of Chris explaining and demonstrating his process. It was shot last year, in advance of a solo exhibition of his work at the University of Michigan Institute for the Humanities Gallery. The show was titled “No-Touching Zone”.]

"No-Touching Zone" – an Exhibition by Chris Hyndman from Donald Harrison on Vimeo.

3 Comments

Katy Perry rode something like your dog at halftime during this year’s Superbowl.

http://www.sen.com.au/media/2954/katy.jpg

Because of this post I’ve been reading entirely too much about tartan patterns. Did you know, “The Dress Act of 1746 attempted to bring the warrior clans under government control by banning the tartan and other aspects of Gaelic culture”?

Read more:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tartan

When I first saw one of Chris’s paintings at a faculty art show at EMU a number of years ago, I was curious by the hard edges and uniform, but brushless paint surface. It was merely curiosity for about a year, until I had him as a professor. After having him as a professor, I have to say what I learned from him about process says much about that the amount of work that goes into his paintings. I learned maybe 20 percent of what he demonstrates in one of his canvases, and I have had the chance to practice an even smaller fraction of the technical ability he demonstrates in his work. His technical knowledge as demonstrated in his canvases well warrants the price tag (and I wish I could afford one of his paintings from the recent past, especially “Mizuno”). As soon as the professors at EMU are given their due recognition, the prestige of the art department at EMU will increase. From what I know about art education, what defines an art program is very often not the success of the students, but of the faculty. I hope he and other professors at Eastern get the credit they are due. I also hope that people in Ypsi realize what gems recent EMU art grads are, how talented they are, and how driven they are to make a viable art scene in Ypsilanti.

One Trackback

[…] thanks to my amazing professors. I mean AMAZING professors. Michael Reedy, Amy Sacksteder, Chris Hyndman, Jason Ferguson, Leslie Atzmon, Brian Spolans and Ryan Molloy – these people literally blow […]