In the early hours of June 26, 2011, 18-year old Deryl Dedmon, who had been drinking with friends, drove his pick-up truck over a man by the name of James Craig Anderson in Jackson, Mississippi, killing him. Dedmon was white. Anderson was black. Dedmon fled the scene of the crime, but, thanks to surveillance camera footage, which showed his truck speeding away, he was eventually brought in for questioning by police. He told officers that he and his friends had witnessed Anderson trying to break into a car, and, when they pulled into the lot to confront him, one thing had led to another. It didn’t take long, however, for detectives to figure out what had actually happened. The young men did see Anderson attempting to get into a car, but they hadn’t simply pulled over to stop what they thought could be a car theft in progress. They pulled over because, in their own words, they’d set out that night looking for a “nigger” to “fuck with.”

These young white men, as the jury would later hear, had been drinking in the small town of Puckett, Mississippi, about 15 miles outside of Jackson, when they decided to leave and purchase more beer. And it was at this point that Dedmon, according to multiple witnesses, suggested that they also look for a black victim or two while in the city. (This was something they’d apparently done on other occasions.) “Let’s go fuck with some niggers,” Dedmon was heard to have said. And, it would seem, this resonated with his friends, who loaded into Dedmon’s 1998 Ford F-250 truck and the Jeep Cherokee of another young man.

And, unfortunately for James Craig Anderson, who was attempting to get into his car in the parking lot of Jackson’s Metro Inn at approximately 5:00 AM that morning, he was the man they selected. According to the testimony of those involved, the young white men robbed and repeatedly beat Anderson, eventually running him over and leaving him for dead. What’s more, one of the perpetrators, during this assault, was heard to yell, “white power” as he walked away from the victim.

Thankfully for these young white men, Anderson’s family asked that they be spared the death penalty. “(These men) have caused our family unspeakable pain and grief. But our loss will not be lessened by the state taking the life of another,” said Anderson’s sister in a letter to the court. “We also oppose the death penalty because it historically has been used in Mississippi and the South primarily against people of color for killing whites. Executing James’ killers will not help balance the scales. But sparing them may help to spark a dialogue that one day will lead to the elimination of capital punishment”… Here’s hoping that she’s right.

Just a few days ago, on February 10, U.S. District Judge Carlton Reeves [seen below] sentenced Dedmon to 50 years in prison; John Rice to 18.5 years; and Dylan Butler to 7 years for their respective roles in the beating and killing of Anderson. (These federal sentences, as I understand it, are in addition to the state sentences handed down for the three, but all sentences will be will be served concurrently.) In his remarks from the bench, Judge Reeves had the following to say about Mississippi’s violent past, the state’s “infatuation with lynching,” and what we should take away from this most recent murder. It’s long, but it’s well worth the time. [Following are the Judge’s prepared statements, which he read from in court during sentencing, after asking the young defendants to sit down and pay attention. You will find a version with footnotes here.]

One of my former history professors, Dennis Mitchell, recently released a history book entitled, A New History of Mississippi

. “Mississippi,” he says, “is a place and a state of mind. The name evokes strong reactions from those who live here and from those who do not, but who think they know something about its people and their past.” Because of its past, as described by Anthony Walton in his book, Mississippi: An American Journey

, Mississippi “can be considered one of the most prominent scars on the map” of these United States. Walton goes on to explain that “there is something different about Mississippi; something almost unspeakably primal and vicious; something savage unleashed there that has yet to come to rest.” To prove his point, he notes that, “[o]f the 40 martyrs whose names are inscribed in the national Civil Rights Memorial in Montgomery, AL, 19 were killed in Mississippi.” “How was it,” Walton asks, “that half who died did so in one state?” — My Mississippi, Your Mississippi and Our Mississippi.

Mississippi has expressed its savagery in a number of ways throughout its history — slavery being the cruelest example, but a close second being Mississippi’s infatuation with lynchings. Lynchings were prevalent, prominent and participatory. A lynching was a public ritual — even carnival-like — within many states in our great nation. While other States engaged in these atrocities, those in the deep south took a leadership role, especially that scar on the map of America — those 82 counties between the Tennessee line and the Gulf of Mexico and bordered by Louisiana, Arkansas and Alabama.

Vivid accounts of brutal and terrifying lynchings in Mississippi are chronicled in various sources: Ralph Ginzburg’s 100 Years of Lynchings

and Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America

, just to name two. But I note that today, the Equal Justice Initiative released Lynching in America: Confronting the Terror of of Racial Terror; apparently, it too is a must-read.

In Without Sanctuary, historian Leon Litwack writes that between 1882 and 1968 an estimated 4,742 Blacks met their deaths at the hands of lynch mobs. The impact this campaign of terror had on black families is impossible to explain so many years later. That number contrasts with the 1,401 prisoners who have been executed legally in the United States since 1976. In modern terms, that number represents more than those killed in Operation Iraqi Freedom and more than twice the number of American casualties in Operation Enduring Freedom — the Afghanistan conflict. Turning to home, this number also represents 1,700 more than who were killed on 9/11. Those who died at the hands of mobs, Litwack notes, some were the victims of “legal” lynchings — having been accused of a crime, subjected to a “speedy” trial and even speedier execution. Some were victims of private white violence and some were merely the victims of “Nigger hunts” — murdered by a variety of means in isolated rural sections and dumped into rivers and creeks. “Back in those days,” according to black Mississippians describing the violence of the 1930’s, “to kill a Negro wasn’t nothing. It was like killing a chicken or killing a snake. The whites would say, ‘Niggers jest supposed to die, ain’t no damn good anyway — so jest go an’ kill ’em.’… They had to have a license to kill anything but a Nigger. We was always in season.” Said one white Mississippian, “A white man ain’t a-going to be able to live in this country if we let niggers start getting biggity.” And, even when lynchings had decreased in and around Oxford, one white resident told a visitor of the reaffirming quality of lynchings: “It’s about time to have another [one],” he explained, “[w]hen the niggers get so that they are afraid of being lynched, it is time to put the fear in them.”

How could hate, fear or whatever it was that transformed genteel, God-fearing, God-loving Mississippians into mindless murderers and sadistic torturers? I ask that same question about the events which bring us together on this day. Those crimes of the past as well as these have so damaged the psyche and reputation of this great State.

Mississippi soil has been stained with the blood of folk whose names have become synonymous with the Civil Rights Movement like Emmett Till, Willie McGee, James Cheney, Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner, Vernon Dahmer, George W. Lee, Medgar Evers and Mack Charles Parker. But the blood of the lesser-known people like Luther Holbert and his wife, Elmo Curl, Lloyd Clay, John Hartfield, Nelse Patton, Lamar Smith, Clinton Melton, Ben Chester White, Wharlest Jackson and countless others, saturates these 48,434 square miles of Mississippi soil. On June 26, 2011, four days short of his 49th birthday, the blood of James Anderson was added to Mississippi’s soil.

The common denominator of the deaths of these individuals was not their race. It was not that they all were engaged in freedom fighting. It was not that they had been engaged in criminal activity, trumped up or otherwise. No, the common denominator was that the last thing that each of these individuals saw was the inhumanity of racism. The last thing that each felt was the audacity and agony of hate; senseless hate: crippling, maiming them and finally taking away their lives.

Mississippi has a tortured past, and it has struggled mightily to reinvent itself and become a New Mississippi. New generations have attempted to pull Mississippi from the abyss of moral depravity in which it once so proudly floundered in. Despite much progress and the efforts of the new generations, these three defendants are before me today: Deryl Paul Dedmon, Dylan Wade Butler and John Aaron Rice. They and their coconspirators ripped off the scab of the healing scars of Mississippi… causing her (our Mississippi) to bleed again.

Hate comes in all shapes, sizes, colors, and from this case, we know it comes in different sexes and ages. A toxic mix of alcohol, foolishness and unadulterated hatred caused these young people to resurrect the nightmarish specter of lynchings and lynch mobs from the Mississippi we long to forget. Like the marauders of ages past, these young folk conspired, planned, and coordinated a plan of attack on certain neighborhoods in the City of Jackson for the sole purpose of harassing, terrorizing, physically assaulting and causing bodily injury to black folk. They punched and kicked them about their bodies — their heads, their faces. They prowled. They came ready to hurt. They used dangerous weapons; they targeted the weak; they recruited and encouraged others to join in the coordinated chaos; and they boasted about their shameful activity. This was a 2011 version of the Nigger hunts.

Though the media and the public attention of these crimes have been focused almost exclusively on the early morning hours of June 26, 2011, the defendants’ terror campaign is not limited to this one incident. There were many scenes and many actors in this sordid tale which played out over days, weeks, and months. There are unknown victims like the John Doe at the golf course who begged for his life and the John Doe at the service station. Like a lynching, for these young folk going out to “Jafrica” was like a carnival outing. It was funny to them – – an excursion which culminated in the death of innocent, African-American James Craig Anderson. On June 26, 2011, the fun ended.

But even after Anderson’s murder, the conspiracy continued… And, only because of a video, which told a different story from that which had been concocted by these defendants, and the investigation of law enforcement — state and federal law enforcement working together — was the truth uncovered.

What is so disturbing… so shocking… so numbing… is that these Nigger hunts were perpetrated by our children… students who live among us… educated in our public schools… in our private academies… students who played football lined up on the same side of scrimmage line with black teammates… average students and honor students. Kids who worked during school and in the summers; kids who now had full-time jobs and some of whom were even unemployed. Some were pursuing higher education and the Court believes they each had dreams to pursue. These children were from two-parent homes and some of whom were the children of divorced parents, and yes some even raised by a single parent. No doubt, they all had loving parents and loving families.

In letters received on his behalf, Dylan Butler, whose outing on the night of June 26 was not his first, has been described as “a fine young man,” “a caring person,” “a well mannered man” who is truly remorseful and wants to move on with his life… a very respectful… a good man… a good person… a loveable, kind-hearted teddy bear who stands in front of bullies… and who is now ashamed of what he did. Butler’s family is a mixed-race family: for the last 15 years, it has consisted of an African-American step-father and step-sister plus his mother and two sisters. The family, according to the step-father, understandably is “saddened and heart broken.”

These were everyday students like John Aaron Rice, who got out of his truck, struck James Anderson in the face and kept him occupied until others arrived… Rice was involved in multiple excursions to so-called “Jafrica”, but he, for some time, according to him and his mother, and an African-American friend shared his home address.

And, sadly, Deryl Dedmon, who straddled James Anderson and struck him repeatedly in the face and head with his closed fists. He too was a “normal” young man indistinguishable in so many ways from his peers. Not completely satisfied with the punishment to which he subjected James Anderson, he “deliberately used his vehicle to run over James Anderson – – killing him.” Dedmon now acknowledges he was filled with anger.

I asked the question earlier, but what could transform these young adults into the violent creatures their victims saw? It was nothing the victims did… they were not championing any cause… political… social… economic… nothing they did… not a wolf whistle… not a supposed crime…nothing they did. There is absolutely no doubt that in the view of the Court the victims were targeted because of their race.

The simple fact is that what turned these children into criminal defendants was their joint decision to act on racial hatred. In the eyes of these defendants (and their coconspirators) the victims were doomed at birth… their genetic make-up made them targets.

In the name of White Power, these young folk went to “Jafrica” to “fuck with some niggers!” – – Echos of Mississippi’s past. White Power! Nigger! According to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, that word Nigger is the “universally recognized opprobrium, stigmatizing African-Americans because of their race.” It’s the nuclear bomb of racial epithets – – as Farai Chideya has described the term. With their words, with their actions – – “I just ran that Nigger over” – – there is no doubt that these crimes were motivated by the race of the victims. And from his own pen, Dedmon, sadly and regretfully wrote that he did it out of “hatred and bigotry.”

The Court must respond to one letter it received from one identified as a youth leader in Dylan Butler’s church, a mentor, he says and who describes Dylan as “a good person.” The point that “[t]here are plenty of criminals that deserve to be incarcerated,” is well taken. Your point that Dylan is not one of them — not a criminal… is belied by the facts and the law. Dylan was an active participant in this activity, and he deserves to be incarcerated under the law. What these defendants did was ugly… it was painful… it is sad… and it is indeed criminal.

In the Mississippi we have tried to bury, when there was a jury verdict for those who perpetrated crimes and committed lynchings in the name of WHITE POWER… that verdict typically said that the victim died at the hands of persons unknown. The legal and criminal justice system operated with ruthless efficiency in upholding what these defendants would call WHITE POWER.

Today, though, the criminal justice system (state and federal) has proceeded methodically, patiently and deliberately seeking justice. Today we learned the identities of the persons unknown… they stand here publicly today. The sadness of this day also has an element of irony to it: each defendant was escorted into court by agents of an African-American United States Marshal; having been prosecuted by a team of lawyers which includes an African-American AUSA from an office headed by an African-American U.S. Attorney — all under the direction of an African-American Attorney General, for sentencing before a judge who is African-American, whose final act will be to turn over the care and custody of these individuals to the BOP — an agency headed by an African-American.

Today we take another step away from Mississippi’s tortured past… we move farther away from the abyss. Indeed, Mississippi is a place and a state of mind. And those who think they know about her people and her past will also understand that her story has not been completely written. Mississippi has a present and a future. That present and future has promise. As demonstrated by the work of the officers within these state and federal agencies — black and white; male and female, in this Mississippi, they work together to advance the rule of law. Having learned from Mississippi’s inglorious past, these officials know that in advancing the rule of law, the criminal justice system must operate without regard to race, creed or color. This is the strongest way Mississippi can reject those notions — those ideas which brought us here today.

At their guilty plea hearings, Deryl Paul Dedmon, Dylan Wade Butler and John Aaron Rice told the world exactly what their roles were… it is ugly… it is painful… it is sad… it is criminal.

The Court now sentences the defendants as follows: [The specific sentences are not part of the judge’s prepared remarks.]

The Court has considered the advisory guidelines computations and the sentencing factors under 18 U.S.C. § 3553(a). The Court has considered the defendants’ history and characteristics. The Court has also considered unusual circumstances — the extraordinary circumstances — and the peculiar seriousness and gravity of those offenses. I have paid special attention to the plea agreements and the recommendations of the United States. I have read the letters received on behalf of the defendants. I believe these sentences provide just punishment to each of these defendants and equally important, I believe they serve as adequate deterrence to others and I hope that these sentences will discourage others from heading down a similar life-altering path. I have considered the Sentencing Guidelines and the policy statements and the law. These sentences are the result of much thought and deliberation.

These sentences will not bring back James Craig Anderson nor will they restore the lives they enjoyed prior to 2011. The Court knows that James Anderson’s mother, who is now 89 years old, lived through the horrors of the Old Mississippi, and the Court hopes that she and her family can find peace in knowing that with these sentences, in the New Mississippi, Justice is truly blind. Justice, however, will not be complete unless these defendants use the remainder of their lives to learn from this experience and fully commit to making a positive difference in the New Mississippi. And, finally, the Court wishes that the defendants also can find peace.

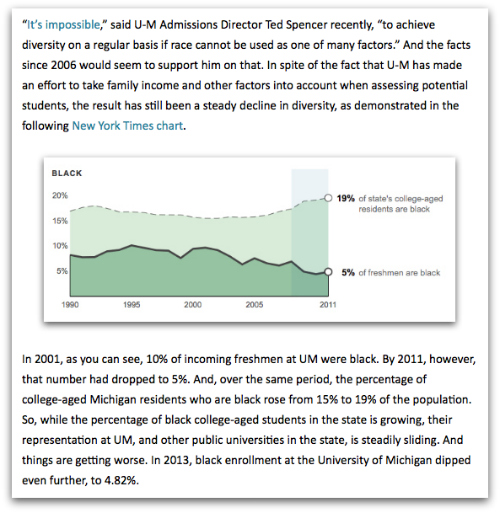

I know this might be something of a tangent, but, as I read this, and reflect on the comments of Judge Reeves, I’m reminded of just how important it is that we have black men and women serving on the bench… and one wonders how things might be worse on that front with the recent Supreme Court decision on affirmative action directed against the University of Michigan. It’s a discussion we’ve had here before, but I think it’s worth having again.

Here, with a bit of the background, is a excerpt from our last conversation on this subject.

Given this fact, and the subsequent decline we’ve seen in black students entering law school, one wonders if a judge, in another decade or two, could say, as Reeves did a few days ago… “(E)ach defendant was escorted into court by agents of an African-American United States Marshal; having been prosecuted by a team of lawyers which includes an African-American AUSA from an office headed by an African-American U.S. Attorney — all under the direction of an African-American Attorney General, for sentencing before a judge who is African-American, whose final act will be to turn over the care and custody of these individuals to the BOP — an agency headed by an African-American.”

[note: Judge Reeves, in his comments, referenced recent work to map incidents of lynching (acts of premeditated murder carried out by at least three white people against black victims) in 12 Southern states between 1877 and 1950. If you’d like to know more, you’ll find an interactive map of the states in question, showing the locations of these lynchings, at the website of the New York Times.]

9 Comments

When I first heard about this case, I didn’t really see it within the context of lynching. While it was clearly a hate crime, it didn’t, at least in my mind, match the definition of lynching as I’d come to know it. Lynching, it seemed to me, while incredibly evil, was typically in response to some act, either real or imagined. Which isn’t, of course, to say lynchings were justified in any way. They weren’t. Mob justice is never justified. And that’s doubly so when, in many of these historic cases, the black men killed were only perceived to have been “guilty” of being politically active or testifying against white men in court. This most recent case, however, seemed like something different, as it lacked even the faintest hint of justification. The men who killed James Craig Anderson didn’t kill him because of something they thought he’d done. Sure, they tried to say that it happened because he was seen breaking into a car, but we know that’s not what really happened. We know that they’d gone out with the intention of finding a black victim to, at the very least, beat into unconsciousness… But then I began wondering about these 4,742-some black men noted by Judge Reeves, who met their end at the hands of lynch mobs between 1882 and 1968, and how many of them may have started not with a perceived offense, but with a desire to “go fuck with some niggers,” as Dedmon put it. I guess we’ll never know, but I suspect what we saw happen just recently in Jackson, Mississippi probably isn’t that rare. I suspect a good number of those 4,742 men died not because they did something to attract the wrath of whites, or were even falsely identified as having done something perceived of as a threat to the white status quo, but just because they happened across the path of angry, insecure white men looking for an opportunity to feel better about themselves by taking the life of someone they felt superior to.

I’d be interested in seeing the statistics from 1968 to the present. It seems natural that it should be included, unless there isn’t as much good news there as we might hope.

I was raised in the heart of Mississippi. I know of what the gentleman speaks and he speaks the truth.

We weren’t even allowed to talk about the Civil Rights movement or slavery while I was growing up. It is still a taboo topic of conversation. Bringing it up will invite anger or dismissal, even from those who would normally criticize racism and racist policy.

I wrote a post on lynching data years ago back when I was somewhat intelligent.

http://peterslarson.com/2010/05/09/lynching-data/

This is also the judge who, in November, overturned Mississippi’s ban on gay marriage.

http://www.clarionledger.com/story/news/2014/11/25/judge-overturns-mississippi-same-sex-marriage-ban/70122842/

From September 20113:

“Black Enrollment Falls 30 Percent At University of Michigan After Affirmative Action Ban”

http://thinkprogress.org/justice/2013/09/25/2677641/black-enrollment-falls-30-percent-at-university-of-michigan-after-affirmative-action-ban/

Can we just let this judge be our supreme ruler? This guy is f’in awesome.

Also, whenever I read of lynching, I remember the first time I ever heard the song “Strange Fruit”. I knew what it was, but first heard it on Sirius Radio on one of the old-timey stations. I actually had to pull my car off the road and sit there shake. The most powerful song (for me anyway).

http://wlrn.org/post/strange-story-man-behind-strange-fruit

Thank you for the link, EOS. I just read it. It was fascinating.

I spent a short period of my life commuting to a job 5 miles off the Mississippi border, also being the only employee that didn’t live in Mississippi. I’m still not comfortable openly talking about the things that I heard and saw there. Sadly this was in 2005.