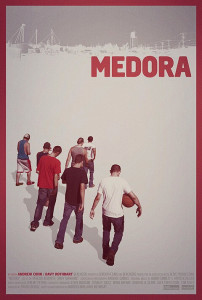

This Thursday night, the documentary Medora will be making its Michigan debut at Ann Arbor’s historic Michigan Theater. The film, which is the most recent production of Found Magazine’s Davy Rothbart, is ostensibly about a small town basketball team’s seemingly impossible struggle to break a two-year losing streak. As you quickly realize when you watch it, though, it’s about a great deal more. It’s about the deindustrialization of the midwest, the defunding of public education, and the increasingly elusive nature of the American dream. As actor Stanley Tucci, who was an executive producer of the film, has said, “It shows how America has cannibalized itself.” And, judging from the accolades the film has been receiving, it’s resonating with people.

Here’s the trailer, followed by my hastily-transcribed interview with the Davy Rothbart, who co-directed the film with fellow Ann Arbor native Andrew Cohn.

MARK: Let’s start at the beginning. It’s Noverber 27, 2009, and John Branch’s article on the the losingest high school basketball team in all of Indiana – the Medora Hornets – runs in the New York Times. As I understand it, within a day, you and Andrew are in a car, driving to the small, depressed, former manufacturing town of Medora. I’m curious as to how things fell together… Had the two of you been talking about doing a documentary project prior to this? Did one of you see the article and call the other? Was this just one of many such trips that you’d taken together in search of the right project?

DAVY: We were just friends, both basketball nuts, passionate documentary film junkies, but we hadn’t been looking for something to make a documentary film about. It was just that this story caught our attention. I’d come home from the 8 Ball and ordered Bell’s Pizza. And I was looking at NewYorkTimes.com, which was kind of my normal routine. And I saw the article. I was totally captivated by it. I can remember that I called Andrew right away. I said, “We’ve got to drive down tomorrow and check this town out.” It was a five or six hour drive, but we hopped in the car… I knew there was some interesting potential there.

DAVY: We were just friends, both basketball nuts, passionate documentary film junkies, but we hadn’t been looking for something to make a documentary film about. It was just that this story caught our attention. I’d come home from the 8 Ball and ordered Bell’s Pizza. And I was looking at NewYorkTimes.com, which was kind of my normal routine. And I saw the article. I was totally captivated by it. I can remember that I called Andrew right away. I said, “We’ve got to drive down tomorrow and check this town out.” It was a five or six hour drive, but we hopped in the car… I knew there was some interesting potential there.

MARK: Was that the first time you’ve done anything like that?

DAVY: I think so. A lot of times, I’ll read an article and I’ll follow up in some way. But I don’t think I’ve ever gone the next day. A lot of times I’ll research it more thoroughly online and try to satisfy my curiosity, you know? But sometimes you learn about a story… Like, there was a guy who used to submit finds to Found Magazine from Kansas City – Byron Case – and I became aware that he’d been locked up for this murder charge, which he, very likely, was not guilty of. I kind of followed the story, and, a couple of months later, I flew to Kansas City. And I went to visit him in prison. And I met with his family. And I ended up making several return visits. I wanted to personally investigate the rest of the story. So, yeah, sometimes there’s a problem, or a situation, or I’ve heard about something one way or another, and I just want to poke my head into it a little further.

MARK: What happened with that story?

DAVY: I wrote about it. The longest essay in my book, My Heart Is an Idiot, is about Byron and his situation. The essay is called, “The Strongest Man in the World.” Byron’s still locked up. It’s bullshit. And I’m still involved with him and his family. And I’m thinking about trying to do a film about it, or finding some other way to spread the word… But, with the Medora story, I knew right away. Andrew and I, since we were kids, would always talk with one another about our favorite documentary films and turn each other on to cool stuff. And I knew this would make a movie. I was sure of it, you know? I knew this would be a great film. But the first step, of course, was to actually go there, and to see the town with our own eyes, and to meet some of the people who live there, and see if it’s something that they might be open to… You know, see what it might take to actually make it happen… But I knew there was a spark of something really fascinating there.

MARK: How were you received? Would I be right to assume that, as the article in the Times had just run, that you weren’t the only ones hoping to talk with the folks at Medora High? Were there other people pitching production deals, and, if so, how’d you manage to come out on top?

DAVY: Yeah, we’re not the only documentary filmmakers to read the New York Times. (Laughs.) There was a deluge… John Branch is a great New York Times writer. He recently won the Pulitzer Prize for his work. He managed to portray, in pretty riveting terms, the plight of this town and its basketball team. We were the first to show up, though. And we met with the Head Coach at the time, and the Athletic Director. And they couldn’t have been more… They invited us to come by their practice. We watched the practice and then hung out for two hours afterward. And it wasn’t to sell them on the idea of a documentary… I just thought, “This piece warrants a visit down to southern Indiana.” And we’d made the trip. But it wasn’t until we’d been with them for a couple of hours, and they were so open with us, that it started to look like it might actually work… They were welcoming, and they shared a number of stories about the players on the team, and just gave us a broader sense of the kinds of struggles that these kids were going through. And then, afterwords, Andrew and I just kind of walked around the town, that’s got a population of less than 500, and we went to the town’s lone bar, called the Perry Street Tavern, and had a beer. And we were like, “Wow.” We could actually imagine ourselves coming and spending eight months or a year in this town. And the idea was incredibly appealing… the thought of getting into that community in a deep and powerful way. And so we just kind of turned to each other and said, “Dude, this is the movie we were born to make.” It just fits so comfortably into our wheelhouse – our areas of interest. I grew up in Ann Arbor, but on a dirt road. And I spent a lot of time in the communities around Ann Arbor that have their Medora-like vibes. And Andrew grew up in Ann Arbor also, but lived in Manchester for a few years. And his mom is from a town in Indiana that’s actually smaller than Medora, where he’s spent a lot of time as well. And we love basketball, and documentaries. We loved Hoop Dreams. And there’s a ton of other basketball documentaries we really loved.

MARK: I’m curious as to how you sold them on the idea of working with you. Was it just that you were there first to town, or was it because they identified more with you than they did with the others? Did they perhaps like that you, as first-time midwestern filmmakers, kind of shared some attributes in common with the team?

MARK: I’m curious as to how you sold them on the idea of working with you. Was it just that you were there first to town, or was it because they identified more with you than they did with the others? Did they perhaps like that you, as first-time midwestern filmmakers, kind of shared some attributes in common with the team?

DAVY: In the weeks following our visit, they had visits from ESPN… David Duchovny’s production company sent someone from their team there… as well as many others. I think they had as many as five proposals from filmmakers who were serious about wanting to come and make a documentary about the team and the town. We all made presentations to the Superintendent. And the town actually said “no” to everybody, including us…

The New York Times piece was very beautiful and evocative, but it also (upset) a lot of people in the town because they prefer to remember the town the way it was, back in its glory days. And the article painted a very accurate portrait of the town and the challenges that it now faces. It was upsetting for some people. So, the idea of having a film crew in, telling essentially the same story, and kicking them further down, was something nobody was excited about. What made the difference for us, I think, is mainly persistence. We kept in touch with them. We kept talking with the coaches, the Athletic Director, and the Superintendent. We let them know that our interest was unwavering. And I think they just came to appreciate, and trust in the sensitivity that we would bring to the story. All of the other people were coming in from New York and LA. And maybe they didn’t have quite the same perspective that we did, as two midwestern guys that maybe had a broader understanding of small towns.

We had no agenda. I think they could tell that we could create a more complete portrait of the town. In the New York Times piece, he only had a certain amount of room. He couldn’t investigate, like, “What are the things that give a town like this value?” Or, “What’s lost when towns like this fade off the map?” You know? Once they lose their schools, these towns disappear pretty quickly. They become like ghost towns. We said, “We aren’t going to shy away from portraying some of the difficulties that may be happening here, but we’ll also film positive things.” They knew we weren’t going to produce a “hit piece,” you know? It’s an accurate reflection of what we really encountering during our time there. We didn’t promise a promotional video of the town, although some people might have wanted that… They have a covered bridge that they’re very proud of, and a maple syrup festival. (Laughs.)

And, you know, they’d heard some of the This American Life pieces that I’d done, like the one on Mr. Rogers, and others. I think they just came to realize that we had a very humanist take. And, in particular, the Superintendent, Dr. John Reed, and the Athletic Director at the time, both really vouched for us. They took an enormous risk by basically letting the School Board members how how much trust they had in us, and basically saying, “We think that these guys are going to make something special that we can all be proud of.”

MARK: Are they proud of it? Have they seen it?

DAVY: Yeah, they are. Dr. Reed came to our Indiana premier in Bloomington. And we still didn’t know what he would think. We’re always nervous about how people will respond. And he had tears in his eyes. He said he was really proud of the film and that he loved it. And we’ve been hearing from people in Medora who have seen it now and they say, “You got it right.” That’s nice, you know? What I take that to mean is that it’s true. The players and some of the family members have said that to us too. “It’s so true,” they say. We captured the stories honestly. It reflects the painful things that they’re dealing with, but also celebrates some of their incredible qualities as well.

MARK: As you note in the film, the issue, to a great degree is structural. Small, local schools are disappearing in Indiana, and they’re being replaced with large, consolidated schools that have enough kids to field highly competitive teams. In stark contrast, the entire student body at Medora High, during the year you were there, was just about 75. And only 33 of those 75 were boys. So the cards are stacked against them. They can’t expect, even under the best of circumstances to ever have a winning season, right?

DAVY: Exactly. That’s the challenge that the basketball team faces, but the same is true of the town. They lost the two factories that sustained them for decades. Both disappeared in the last 10 to 20 years, so there’s really no employment there. And this town that was once flourishing, with over 2,000 people, now has less than 500 remaining… There’s also a lot of farming there as well, but that’s been struggling of late too… So there are all of those other things that come into play when you have joblessness and poverty.

MARK: I know you’ve said that you didn’t want this to be an “issue” movie, but clearly you touch on a lot of important stuff, like what happens to a community when manufacturing jobs go elsewhere. You didn’t note it in the film, but I’m curious as to what happened to the two plants that had been operating in Medora. Did either of them relocate in hopes of finding cheaper labor elsewhere?

MARK: I know you’ve said that you didn’t want this to be an “issue” movie, but clearly you touch on a lot of important stuff, like what happens to a community when manufacturing jobs go elsewhere. You didn’t note it in the film, but I’m curious as to what happened to the two plants that had been operating in Medora. Did either of them relocate in hopes of finding cheaper labor elsewhere?

DAVY: One got liquidated in a Bain Capital kind of way. Some big corporation bought it, and then closed it down and gutted it. Andrew has a more clear understanding of how it all worked. It’s something that he’s interested in. But it’s one of those common stories these days. That was the plastics factory. I’m not sure about the brick plant.

MARK: Speaking of social issues, school consolidation looms large over the terrain of this film. The people in the small town of Medora want desperately to keep their local school, but, with budget cuts, and a dwindling tax base, it looks like the writing may already be on the wall, and that, sooner or later, they’ll have to sucumb to consolidation… I’m curious as to whether this experience has made you any more appreciative of the role of local schools in a community… Has this experience made you more political about these issues?

DAVY: Definitely. I now have a first-hand understanding of the issues at play. A lot of people have watched the film and asked, “Wouldn’t these kids have better opportunities at a consolidated school?” They’re better funded, have a wider range of classes… Instead of having one foreign language, they might have six, you know? And better computer centers, and all these other things. What’s interesting is the response from Dylan (McSoley), Rusty (Rogers), and some of the other players who have been traveling with us these past few weeks, sharing the film. I think it was Dylan who said recently, “It’s the kids who come from these small, poor towns like Medora who fall through the cracks when they go to these large consolidated schools.” Just the gas money it takes to drive the half hour to school, when you could just walk to school before… To try to make it there on days when there’s bad weather… And those are the kids who often feel out-of-place in a bigger school. And also you hear Rusty and his friends talking about the small class sizes at Medora, and the one-on-one time they have with teachers. And also just a sense of identity and heritage… Going to school where your parents and grandparents went. Being in school with the people from the community that you grew up with. You just see the value of it in a town like Medora, where kids are struggling. You see it in the film – people reaching out a helping hand. Rusty, who was essentially homeless when we first arrived, and living in his car, the way his best friend and his friend’s mom would invite him to stay with them for months at a time. And Dylan, the kid who didn’t know his father, you see the way his ex-girlfriend’s grandfather (offered him advice)… People like that. You see how they play the role of family for people with absent parents.

We came to love Medora and saw so many great qualities. Our hope is… The future of Medora is unclear, certainly, and they don’t have an easy path ahead of them, but… People within the state have been trying to close the school for the last 20 years, and our hope is that if the film makes it that much harder for them to close the school. That would be a good thing.

MARK: One of my favorite quotes from the Times piece came from Medora junior varsity coach Matt Rotert. “I don’t think they’re used to people expecting something out of them,” he said of the boys on the high school team at the time. Clearly, with the launch of this film, there’s been a lot of attention on these young men, and, rightly or wrongly, people are expecting things from them… I’m curious as to how they’re holding up now that they’re out of high school and in the limelight.

DAVY: They’ve been amazing. They’re 19, 20, 21 now. And, oh my god, the way they handle themselves during these Q&As… You should see how thoughtful Dylan and Rusty are… Zach (Fish) has been on the road with us too. In the film, you don’t always see it. He’s drinking a lot. But he’s a really a sweet and kind kid. Him and his mom have taken in 10 kids like Rusty over the years. And that’s due a lot to Zach being such a caring guy, looking out for his friends. Sometimes they say things during the Q&A that just takes the collective breath away from everyone, something just so beautiful, and meaningful, and honest.

MARK: Do you have an example?

DAVY: Yeah. Someone was asking about Chaz (Cowles), and how he was always in trouble, and what he’s up to now. And Dylan shared a story about how, although Chaz is often seen as a troublemaker by others in the community, Chaz was the first person to approach him when he first moved to Medora, and say “hi” to him. Dylan also said, “Even though people saw him as wild, or troubled, I saw him as a human trying to sort through things.” I can’t remember exactly how he put it, but it was really touching. These guys have a lot of perspective into their own lives, and their town. And, yeah, they’ve stepped up. And they’ve been having a blast too. They told me that Bloomington, Indiana seemed overwhelming (when we got there) and it’s only half the size of Ann Arbor. So then to be in Manhattan was just… (Laughs.) And to fly on planes for the first time. To be out of southern Indiana for the first time. You think it would be totally intimidating, but they’re just rolling with it and having fun. And the other thing is, at the events they’ve just been so talkative. Everyone falls in love with them after seeing the film. How could your heart not go out to them? And they’ve been so gracious talking with everyone. I just love the way they carry themselves. You really do see them growing before your eyes. And now they’re like peers. It’s just fun to hang out and play pool.

MARK: Having not done anything like this before, how do you jump in and make something like this work? Specifically, I’m curious as to how, as new directors, you were able to be in the moment with your subjects and yet not influence the action. In other words, I imagine that successful documentary filmmakers, like the Maysles brothers, have, over time, developed methods of interacting with their subjects, and I’m curious as to how you just jumped right in and did it… Were you concerned about becoming friends with the students on the team? Did you try to keep your distance? Or did you purposefully go the other route in an attempt to gain their trust by being their friends?

DAVY: We became really close friends during our time there. It might sound weird to say that we had no plan, but it wasn’t really something that we discussed. We just wanted to get to know them. And sometimes that meant putting the cameras down and just playing basketball with them, or having dinner with their families. Just kickin’ it, I guess. (Laughs.) We watched tons of basketballs games with them. But mostly it was fly-on-the-wall filmmaking. We were just there with cameras, hanging out, while they were doing their own thing.

MARK: In retrospect, is there anything you would have done differently?

DAVY: I didn’t get to play enough basketball with them. I always felt like, “Well, I really should be filming in case something interesting happens, or they say something interesting.” But there was never a concern that we would influence the action… When they asked for advice, we gave it to them, the way a mentor or somebody might. And it went both ways. Dylan always talks about the two-way friendship that grew. We’d tell them what was going on in our lives and they’d give us advice. It was just like any friendship… The only awkward moments happened because they’d become so used to the cameras. We’d just kind of faded into the background pretty quickly. Sometimes they would go on dates with girls from another high school or something, who weren’t used to seeing the cameras around. So, like Dylan would pick up a girl to take her to the bowling alley on Friday night, and she’d get in the car and say, “Uhhh, who’s the scruffy looking guy with the camera in the back seat?” (Laughs.) Literally, he would sometimes forget to give them advance warning.

MARK:. I’m curious about the fundraising side of things… As I understand it, you bootstrapped along, using your own money, and borrowed equipment, shooting for almost an entire year in Medora. Then, after you’d shot 600 hours of film, when it came time to hire an editor, you turned to Kickstarter with a goal of $18,000, hoping, I’m assuming, that you could get enough of a rough-cut to have something to show investors. Instead, you raised $65,000. How far did that get you? And where did you turn after those funds were gone?

MARK:. I’m curious about the fundraising side of things… As I understand it, you bootstrapped along, using your own money, and borrowed equipment, shooting for almost an entire year in Medora. Then, after you’d shot 600 hours of film, when it came time to hire an editor, you turned to Kickstarter with a goal of $18,000, hoping, I’m assuming, that you could get enough of a rough-cut to have something to show investors. Instead, you raised $65,000. How far did that get you? And where did you turn after those funds were gone?

DAVY: Yeah, we funded it originally out of our own pockets. All that first year that we shot in Medora, and the second year, during which we kept making trips back. And with Kickstarter, we knew that $18,000 was just a fraction of what we’d need, but it seemed like a reasonable goal. And we thought we’d be lucky to achieve it. And when we received $65,000 from contributors, we were just thrilled. It meant not only that we had more resources going forward, but that the film was really resonating with people. We’d always believed that it was a powerful story, but to see that it meant so much to so many other people was exciting. So that money went pretty fast over the course of that year, as we tried to edit 600 hours down to 80 minutes, or feature-length. Eventually we needed more resources, so Beachside Films came in. They’ve done great indie films like Little Miss Sunshine, Safety Not Guaranteed

, and a bunch of other ones like that. They were able to help out with hiring a second editor, Mary Manhardt, this elite editor who’s worked on all of these amazing documentaries over the years like The Farm: Life Inside Angola Prison

and Street Fight

, which is about Cory Booker, and one of my all-time favorite films. And even just stuff like music, color, sound. There’s so much that goes into completing a film. Stuff that I wasn’t even fully aware of. And, so, having their stewardship and resources helped us get to the finish line.

MARK: Did you find it difficult at all ceding some control to them?

DAVY: (Laughs.) You know… Yes. We had very specific ideas… There were certain creative decisions, you know? …How to handle a music cue. Which shot to select… You’re inviting other people into your creative space. You’re no longer doing it autonomously. And yet, you know, they have a great track record. I mean, there’s a reason that they’ve done so well over the years. They’re smart guys. They’re not Hollywood assholes. They’re genuine guys who care about a story like this. There’s a reason they were attracted to this story. They share some of our sensitivities. That doesn’t mean that there weren’t moments when we disagreed about stuff, but this film is really about collaboration and having other voices in the room actually helps make it a better film. So we were lucky not only to get their resources, but their creative guidance too.

MARK: But in terms of the narrative arc, you were all pretty much in agreement as to the kind of story that you wanted to tell with the raw footage? So the disagreements were more about music cues, and less about vision… There wasn’t, in other words, one contingent pushing for it to be more like Hoosiers, and one pushing for it to be more like Gummo

?

DAVY: No, we were pretty much all on the same page. The narrative structure is all stuff that you discover through editing, sitting with the footage, and talking about it. You try one thing. You try another thing. We’d invite 10 or 15 friends in New York into a room to watch it, and we’d hear their response. And we’d go back to the editing room. It’s a very long process but it’s rewarding. You make new little discoveries. You see the film gradually get better.

[If you’d like to see Medora for yourself, general admission tickets to the premier are $10 ($8 for students). And doors open at 7:00 PM on Thursday, December 12. VIP tickets are available for $25, which include entry to a special reception in the Michigan Theater lobby from 5:30 – 6:30 PM, food, a free drink, priority seating, and a copy of the Medora DVD. Tickets can be purchased here.]

14 Comments

Looking at it analytically, it was s good business decision. Either they went there and captured a third losing season, which would yield great footage, or they went there and captured the team’s first win in three years. For the reasons noted in the interview, there was no way they were suddenly going to be a middle of the road team, winning a significant number of games.

I wonder what town he could be talking about when he mentions spending time in a place outside of Ann Arbor with a “Medora like” vibe.

In other news from Indiana.

Read more:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-india-25329065

It’s not just a covered bridge, it’s said to be the longest historical covered bridge in the United States (438 feet).

Here’s a photo.

http://www.cyberindiana.com/images/jackson/medora/pix/medora_covered_bridge.jpg

I sucked at sports and no one ever made a movie about me. :(

I know I shouldn’t be jealous, but, when it comes to DR, I can’t help myself. Everything he touches seems to turn to gold.

No one’s life is perfect. Not even Davy’s.

http://nymag.com/news/features/70976/

I never really liked basketball.

This is a great interview, but it only has 4 LIKES. Does that speak to Davy fatigue?

If Hoke stays at Michigan, in a few years they could do a similar movie about the football team.

Who’s Davy Rothbart? I’ve never heard of him.

Arthur A.–right? I admire people like him who are successful but at the same time I wonder what they have that I don’t. Is it just hard work and I lose interest too quickly?

Peter Larson–keeping it real :)

I was hoping that DR actually punched DD.

Medora premieres March 31st on PBS’ Independent Lens.