Today marks the 107th anniversary of former-Yopsilantian Winsor McCay’s surrealist, illustrated masterpiece Little Nemo in Slumberland, and, to mark the occasion, the folks at Google have rolled out an incredible new, interactive header, which you can see in action in the following video.

The following is from the Christian Science Monitor.

The Google homepage today depicts an old-fashioned comic strip, in muted hues of blue, red, green, and yellow. Click on the tab on the bottom right of the doodle, and watch a pajama-clad boy tumble, panel by panel, through a fairytale land of clouds, castles, and princesses, before finally landing back in his own bedroom. The doodle is an homage to the artist Winsor McCay, and his most famous creation, Little Nemo, which turns 107 years old today.

McCay was born in Canada, probably around 1867 or 1868 – the exact date and location remain unclear. When McCay was still a child, his family moved from Canada to Spring Lake, in Michigan. The young McCay drew fervently, and around 1880, one of his illustrations, of a sinking steamer, was apparently snapped up for use in postcards.

Eventually, McCay was discovered by John Goodison, a drawing professor at Michigan State Normal School. Goodison agreed to tutor McCay informally, although McCay never officially enrolled at (what is now Eastern Michigan University)…

And, here, with more on McCay’s time in Ypsilanti, is a clip from the very much missed Ypsilanti Citizen, written by local historian Laura Bien.

…Zenas, who later called himself Winsor, loved to draw since childhood. His father had a more practical career in mind.

In 1886, Winsor and three friends came to Ypsilanti to attend the Cleary Business College. The friends rented a large room together. Ypsilanti was bigger and more bustling than Spring Lake.

However, according to one 1880’s Cleary advertisement, “the innumerable attractions of city life which alienate the attention of students from their studies are not to be found in Ypsilanti.”

But Detroit had one such attraction — Sackett and Wiggin’s Wonderland, a dime museum.

Created by P. T. Barnum in 1841, dime museums were a sort of walk-through version of the Victorian “cabinet of curiosities.” The museum’s ostensible purpose, according to Barnum, was education and moral improvement through entertainment. Dime museums presented a heterogeneous mix of freak shows, circus performances, religious tableaux and sometimes less savory displays—for personal edification.

Winsor loved drawing the varied scenes in the dime museum and eventually became one of the attractions, working there as a caricature artist.

In 1888, Winsor displayed a drawing in downtown Ypsilanti. “The work of Art exhibited at the Post Office by Winsor McCay,” said the Feb. 10, 1888 Ypsilanti Commercial, “is a great credit to the young man’s artistic ability.”

That ability caught the eye of Normal School geography and drawing professor John Goodison.

Goodison entered the Normal School in 1856 and taught there until his death in 1892. An “In Memorium” in the 1893 Normal School yearbook singles out his patience, perseverance and intelligence—when he wanted to read a geography text written in German, he taught himself German.

When Goodison recognized the talent in McCay’s work, he met with and praised the young artist.

Goodison had worked in stained glass before teaching at the Normal and one source says McCay developed his vivid palette in part from the influence of Goodison’s stained glass. Less uncertain is that Goodison imparted a strong sense of the power of perspective in art to McCay, whose later “Little Nemo” comic strip is noted for unusual, sometimes breathtaking, perspectives.

Goodison encouraged McCay. In 1889, McCay left Cleary Business College for Chicago and found work drawing advertising posters for a circus.

He moved to Cincinnati, married and then moved to New York. In 1904 his comic strip “Dreams of the Rarebit Fiend” began in New York’s Evening Telegram.

The strip presented a series of gradually more surreal events. The last panel always shows someone waking in bed from a dream, regretful for having eaten some odd food, usually rarebit…

And the rest, as they say, is history. His masterpiece, Little Nemo in Slumberland, began appearing in the New York Herald on October 15, 1905. (It later started running in William Randolph Hearst’s New York American newspapers.)

Just a few quick notes, as I’m about to drift into Nemo-like slumber.

1. I’d lobbied to name my son Nemo. I lost. While Linette likes the work of McCay, and found the Ypsi connection interesting, those things apparently weren’t enough to outweigh the fact that there was another Nemo in popular culture – a brilliant, yet blood-thirsty man of science, driven to madness by his all-consuming quest for vengeance. (I believe I told Linette that I’d wanted to name our son in tribute to McCay’s visionary young protagonist, but, truth is, I kind of like the idea of my son growing up to be an idealistic scientist-loving pirate revolutionary.)

1. I’d lobbied to name my son Nemo. I lost. While Linette likes the work of McCay, and found the Ypsi connection interesting, those things apparently weren’t enough to outweigh the fact that there was another Nemo in popular culture – a brilliant, yet blood-thirsty man of science, driven to madness by his all-consuming quest for vengeance. (I believe I told Linette that I’d wanted to name our son in tribute to McCay’s visionary young protagonist, but, truth is, I kind of like the idea of my son growing up to be an idealistic scientist-loving pirate revolutionary.)

2. Wouldn’t it be cool if we had an Ypsi Exit Interview with the young Winsor McCay? And, even cooler still, what if one of the brilliant young people that I’ve interviewed over the course of the past several years, ends up doing work that’s similarly revolutionary? Who’s to say that one of the young people that we’ve talked to here, as they’re making their way out of Ypsilanti, won’t create a new field of artistic endeavor.

3. I don’t know where we’d put it, but we should have a plaque somewhere in the City noting the fact that McCay learned his trade here.

4. I find it interesting that Google could do this with McCay’s work, but probably couldn’t do the same thing to commemorate the first appearance of Micky Mouse in Steamboat Willy due to copyright restrictions still enforced, now almost 90 years later, by Disney.

5. I didn’t like the use of the ET soundtrack in the video above. I get what they were going for, but I found it distracting. I would have preferred something more appropriate to the time.

6. I don’t know that anyone’s ever seriously compared the two, but I think it would be fascinating to look at the careers of Winsor McCay, who first started creating animated films in 1911, and Walt Disney, who gained widespread popularity in 1928 with Steamboat Willie. What accounts for the difference in their career trajectories, I wonder. Why was McCay relegated to showing his wildly innovative films on the Vaudeville circuit, when Disney went on to create a multi billion dollar industry? Was it all timing? Was it Disney’s business acumen? If McCay had been willing to hire animators, and create an animation factory, might we all be taking our kids to Winsor McCay World right now? Or, did Disney just have a better eye for what the public wanted? Was McCay too cerebral? Or, did Disney just have the good fortune of starting out at a time when synchronized sound was becoming possible? I’d love to know what it was, and what McCay made of Disney’s success.

7. I like that Cleary Business College, back in the 1880’s, advertised the fact that there was nothing going on in Ypsi to distract students. I’d love to see EMU use the phrase, “the innumerable attractions of city life which alienate the attention of students from their studies are not to be found in Ypsilanti,” in their marketing materials.

8.Although local puppeteer Naia Venturi named Ypsilanti’s Dreamland Theater in honor of Winsor McCay, she didn’t know, until I mentioned it to her a few years ago, that he’d actually lived here in town, and likely walked right by the front door of what’s now the Dreamland Theater hundreds of times. I find that an incredibly cool coincidence. (I love serendipity.)

9. Here, for those of you who have never seen McCay’s animated work, is Gertie the Dinosaur, from 1914.

“Unlike any comic strip before or since… (Little Nemo in Slumberland) represented a major creative leap, far grander in scope, imagination, color, design, and motion experimentation than any previous McCay comic strip (or those of his peers).” -McCay boigrapher John Canemaker

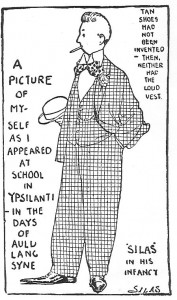

[note: The accompanying single-panel comic, which he signed using his alias, Silas, was the only image of his that I could find that referenced Ypsilanti. I’m sure there are others, though, and I intend to keep searching.]

7 Comments

If you were to name a kid Nemo these days, the other kids would mock him for being named after a fish.

Does any of the work that he produced while in Ypsi still exist? Assuming he drew images of things that I saw around town, it would be fascinating to see them.

The depiction of the African character might be seen as racist by today’s standards, but I like his hand-colored animation in this 1911 piece. The movement is awesome.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kcSp2ej2S00

He was inspired to try animation by flip books of his son.

Read more:

http://www.filmreference.com/Writers-and-Production-Artists-Lo-Me/McCay-Winsor.html#ixzz29TXQvMyY

Animation was always a sideline for McCay; he was a full-time newspaper cartoonist. In his later career, “Little Nemo” was axed as too old-fashioned; his boss wouldn’t let him do vaudeville; and his working hours were taken up drawing elaborate political cartoons to order. His political cartoons were beautifully drawn, and paid well, but didn’t leave much time for more creative work. He continued to experiment with animation (and did hire assistants), and spent too much time trying to get his son started as a cartoonist. He was apparently not a particularly good businessman. I’m sure there are lessons in there…

Here’s an oddity: a comic book version of Little Nemo, by McCay’s son. Huh!

http://fourcolorshadows.blogspot.com/2010/06/nemo-in-adventureland-bob-mccay-1945.html

I wish new students coming to Ypsi looked that way now. That would be an incredible improvement.

One Trackback

[…] when it comes to innovation, entrepreneurship and boundary pushing. Preston Tucker, Iggy Pop, Winsor McCay and Elijah McCoy all called Ypsi home. That’s an amazing tradition of visionary iconoclasts. […]